ART TRIBUTE:The Allure of Matter Material Art from China,Part III

Since the 1980s, artists working in China have experimented with various materials, transforming seemingly everyday objects into large-scale artworks. These artists have exploded fireworks into paintings, felted hair into gleaming flags, stretched pantyhose into monochromatic paintings, deconstructed old doors and windows to make sculptures, and even skillfully molded porcelain into gleaming black flames (Part I), (Part II).

Since the 1980s, artists working in China have experimented with various materials, transforming seemingly everyday objects into large-scale artworks. These artists have exploded fireworks into paintings, felted hair into gleaming flags, stretched pantyhose into monochromatic paintings, deconstructed old doors and windows to make sculptures, and even skillfully molded porcelain into gleaming black flames (Part I), (Part II).

By Efi Michalarou

Photo: Smart Museum of Art Archive

Too large for a single venue, the exhibition “The Allure of Matter: Material Art from China”, takes up the full gallery footprint of Smart Museum of Art and Wrightwood 659 in Chicago, bringing together 48 two- and three-dimensional works made from a range of unique and humble materials in which conscious material choice has become a means of the artists’ expression, representing this unique trend throughout recent history.

Wang Jin’s many performance and environmental projects since the early 1990s reflect upon the rapid spread of capitalism in China, as well as other social and political issues. Wang’s incisive works comment on the clash and fusion of new and old values by staging ironic combinations of foreign and Chinese symbols. Originally created for one of the first domestic auctions of contemporary art in Beijing in 1997, “A Chinese Dream” faithfully reproduces Peking Opera costumes and imperial robes of the Qing dynasty using translucent PVC plastic sheets. The imperial robes and theatrical costumes levitate like specters of a bygone age. Such garments traditionally bear encoded symbols, such as five-clawed dragons representing the imperial house, or the multicolored waves, rocks, and clouds that present the universe under the ruler’s sway.

Hu Xiaoyuan gained international attention for her work “A Keepsake I Cannot Give Away” (2005-066), which features delicate silk embroidery. Expanding her material explorations shortly thereafter, Hu had a breakthrough with her 2008 “Wood” series, which juxtaposed silk, wood, and nails. In these works, Hu placed a piece of silk on top of a board and meticulously traced all of the visible wood grain onto the silk. Then, she put the silk aside and covered the wood surface with white paint, obscuring the grain. Finally, she framed the silk over the board using tiny nails, as if stretching a canvas on a wooden frame. Deceptively simple, these finely painted objects require careful scrutiny to uncover the subtle contradictions between representation and reality. In the two geometric sculptures “Ant Bone IV” and “Ant Bone V” Hu employed traditional mortise-and-tenon joints used for centuries in Chinese woodworking and architecture. On each form’s interior, Hu carefully covered the wood with her signature paintings on silk. The interplay between the wood, silk, and nails draws out the tensions between what is hard and soft, real and fake, old and new.

Jin Shan turned to plastic as an art material in 2013 to exploit the material’s ability to express “a nasty feeling”. Jin was inspired by plastic’s incredible flexibility—it can be easily melted, poured, stretched, and sculpted. Since then, Jin has continued to give expression to such plasticity by exploring ways to retain the appearance of melting plastic even after it has hardened into a shape. The artist often combines plastic with other materials to produce complex sculptural assemblages, often reflecting a rebellious spirit. This dynamism and movement is evident in “Mistaken”. Fists punch out from the half-melted plastic face of a heroic Communist worker, yet the plastic appears to disintegrate into fine threads. The sculpture’s lower part is made up of an aggressive arrangement of wood slats. The wooden pieces, chopped by Jin himself, are made from the wooden doors of old, demolished houses on the outskirts of Shanghai. The dramatic contrast of the two materials: the wooden relics of old buildings and the plastic Cultural Revolution imagery, suggests the fragmented memories of China’s past.

For the work “Chains: The Unbearable Lightness of Being, Nature Series, No. 79”, Liang Shaoji covered hollow metal chains in delicate, raw white silk. Here, the silkworms not only create the material but also become live participants—stand-ins for the artist. Liang blurs the boundaries between his role as an artist and the worms with whom he co-creates this artwork, opening larger questions on the distinction between art and nature. Furthermore, his fascination with silk is rooted in the Chinese psyche: Chinese legends connect the invention of silk-making with the creation of Chinese civilization. It is said that the Yellow Emperor, Huangdi, or his wife, Lady Xiling, actually discovered the method of raising silkworms and spinning silk.

Working with plastic, meat, and then fruit, Gu Dexin was one of the first artists to use unconventional materials in China. In the early 1980s, Gu melted scrap pieces of plastic he took home from a plastics factory in Beijing where he worked part-time. The resulting abstract forms were a radical departure from his earlier paintings and from the realistic and representational styles of art that dominated the mainstream of artmaking in China at the time. Gu became fascinated by plastic’s texture and versatility. In the untitled room-sized installation featured in this exhibition, Gu assembled a colorful array of contorted, organic, and raw forms made from molded plastic, emphasizing the tactile and versatile nature of the material.

As a teenager, Liu Jianhua was introduced to porcelain by his uncle, a ceramist in the famous porcelain-making city of Jingdezhen. This early exposure was influential: since then the artist has used the pure white clay to produce all of his work. “Blank Paper” and “Black Flame”, two of Liu’s porcelain works featured in this exhibition, explore the characteristics of porcelain and infuse them with a contemporary sensibility. Often displayed in a row on a wall, Liu’s blank porcelain papers simultaneously challenge the viewer’s eyes and mind. Inspired by the unique properties of porcelain, the artist remarked, “Although one can use fiberglass, steel, wood, stone, or any other material to represent a piece of paper, none of them can compete with porcelain that only comes into existence after being fired at over 1,000 degrees Fahrenheit. “Black Flame” consists of eight thousand black porcelain flames that suggest the possibility of a rapidly spreading fire flickering across the gallery floor. The glaze is a key element of this work: its matte shade creates layers of pure blackness. The pool of sharp flames appears menacing; in stark contrast to the calming quality of “Blank Paper”, it is imposing. As a pair, these two works show us the range of emotions that porcelain can elicit, through two very different manipulations of the material.

When Gu Wenda first moved to the United States in the early 1990s he began experimenting with different bodily materials. In 1993, he intermingled and felted strands of hair collected from around the world into a large-scale installation. Since then, Gu has continued to use hair as the main material in his ongoing “united nations” series. Conceived as “national monuments” for multiple countries around the world, each monument was composed with hair collected from the local community as its basic material. Shaping the hair with glue into transparent tapestries, on which he would inscribe cryptic pseudo-calligraphic texts using human hair, Gu envisioned that the project would culminate in “a giant wall composed of pure human hair integrated from all of the monuments in the series”. Such a monument would symbolize a utopian world in which all races coexist in a state of natural harmony. For “american code” colorful braids of hair form a tent that encloses a flag, similarly made from hair. By bringing together hair from disparate groups of people from around the world, Gu evokes the United States’ identity as a nation of immigrants. However, the flag hanging in the center of the monument does not belong to any particular country; rather, it is made up of a generic star and stripes formed by pseudo-scripts. By weaving together this common but profoundly personal material, Gu reflects on the relationship between human interconnectedness and distinct personal identities.

Growing up during the decades of drastic urban development that followed the end of the Cultural Revolution (1966–76), Liu Wei became interested in the detritus of urban consumer culture: junked appliances and demolition debris. These scrap materials are commonly found in the demolition sites of traditional middle-class courtyard houses and the construction sites of new high-rises in Beijing. Employing the assistance of local laborers, Liu collected and recycled these materials by hacking them apart with chainsaws, branding them with bold statements, and bolting them together to form colorful sculptural abstractions. Each work from the “Exotic Lands” and the “Merely a Mistake” series features these reused junk materials. Whether hanging on the wall or built up into large-scale architectural structures, the works seem to suggest a futuristic metropolis. Seen again more closely, however, they reveal cuts, peeling paint, nail and screw holes, rot, and broken edges, suggesting the remains of a bygone Beijing.

Coca-Cola was already widely consumed in China by the time He Xiangyu began his first major work of art, “Cola Project” (2008-12). As part of this series He manipulated the soda, subjecting it to physical and chemical (or alchemical) change. For many, Coca-Cola is an icon of Western culture and consumerism, however, He has transformed this ubiquitous product into a medium for artmaking. He’s process consisted of boiling down 60,000 bottles of Coca-Cola in batches, destroying the soda itself in the process, until he was left with desiccated cola-ash. At first, He worked alone, and it took more than six months to boil down one ton of soda. With the help of a crew of migrant workers, all working in a lumber mill outside He’s hometown of Dandong, Liaoning, however, the artist industrialized his process to mass-produce the soda ash. In total, the artist reports boiling down 127 tons of soda.

Since her early childhood, Lin Tianmiao has been fascinated with cotton thread. Her mother would tediously unravel the thread of the white cotton gloves given to workers in state-owned factories to make new clothes and mend others. Lin appropriated this domestic task in the early 1990s, wrapping hundreds of household objects in white thread. For Lin, binding represents a form of corporal punishment that women experience in their daily housework and in domestic labor. In the work “Day-Dreamer”, included in this exhibition, Lin suspends hundreds of cotton threads along the outline of her self-portrait. The haunting silhouette suggests the impact of this labor-intensive process on her body.

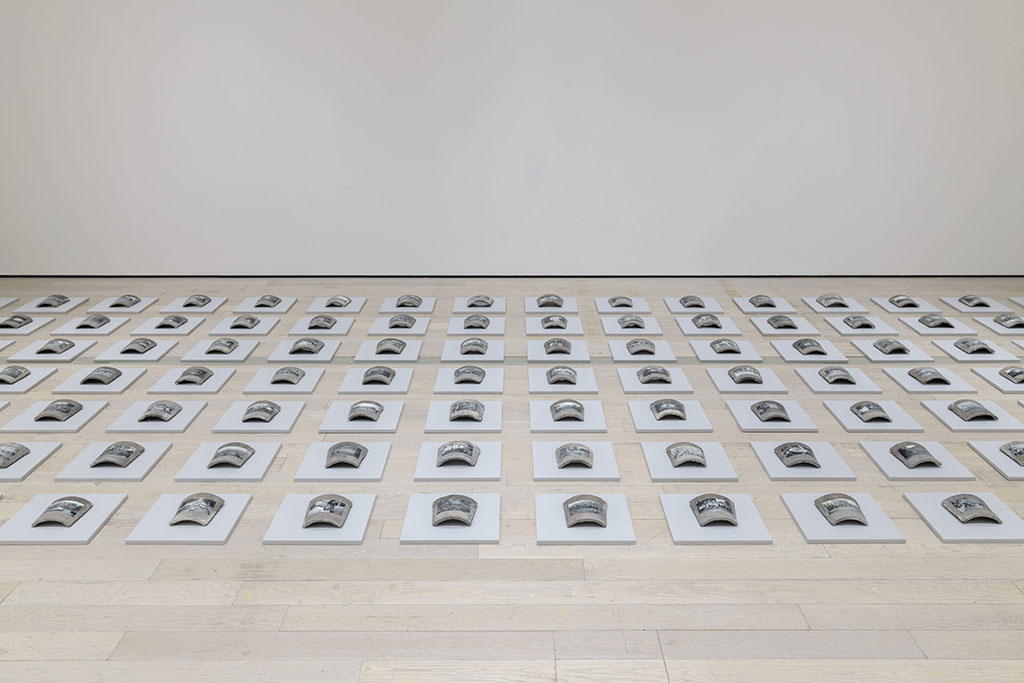

Born and raised in Beijing, Yin Xiuzhen grew up in one of the city’s many siheyuan, or courtyard houses, that were demolished during the urban reconstruction efforts conducted in the 1990s. Many traditional houses were removed to make room for gleaming high-rises and new infrastructures. Sensitively reflecting on the transformations around her, Yin produced a number of installations that incorporated the forgotten remnants of such destruction. For “Transformation”, Yin collected 128 cement roof tiles from the thousands that were discarded after the demolition of these siheyuan in her Beijing neighborhood. On each tile, she affixed a photograph documenting the vibrancy of the neighborhood and its changing character. For Yin, these unconventional materials embodied the memories of a place and time period that was rapidly disappearing.

In the late 1980s Xu Bing garnered international attention for his formal experiments with the Chinese written script by using the traditional medium of woodblock carving and printing to produce an extensive series of nonsense characters. Since then Xu has expanded this interest to explore the ways in which the written script could bridge different systems of writing and engage audiences across different cultures. Xu’s ambitious “Tobacco Project” (2000-11) combines these various interests. In 2000, during a residency at Duke University, Xu started his research on tobacco, its consumption, and its global circulation. Using tobacco as both material and subject, the artist explores the history and production of the cigarette, global trade, and marketing in his long-term Tobacco Project. Tobacco was one of the first products from the United States to enter the Chinese market. Fascinated by this US-China connection, Xu transformed different aspects of raw tobacco leaves, cigarettes, and cigarette packaging and other marketing materials to explore the interwoven histories of the global economy, commodities, and Chinese art history.

Info: Wu Hung and Orianna Cacchione, Smart Museum of Art, The University of Chicago, 5550 S. Greenwood Avenue, Chicago, Duration: 7/2-3/5/20, Days & Hours: Tue & Fri-Sun 10:00-17:00, https://smartmuseum.uchicago.edu & Wrightwood 659, 659 W. Wrightwood, Chicago, Duration: 7/2-3/5/20, Days & Hours: Thu-Fri 12:00-20:00, Sat10:00-19:00, https://wrightwood659.org

Right: Xu Bing, Traveling Down the River, 2011, Burned cigarette on a scroll in glass case, Scroll: 25 x 699 cm, Collection of the artist, Photo © Museum Associates/LACMA

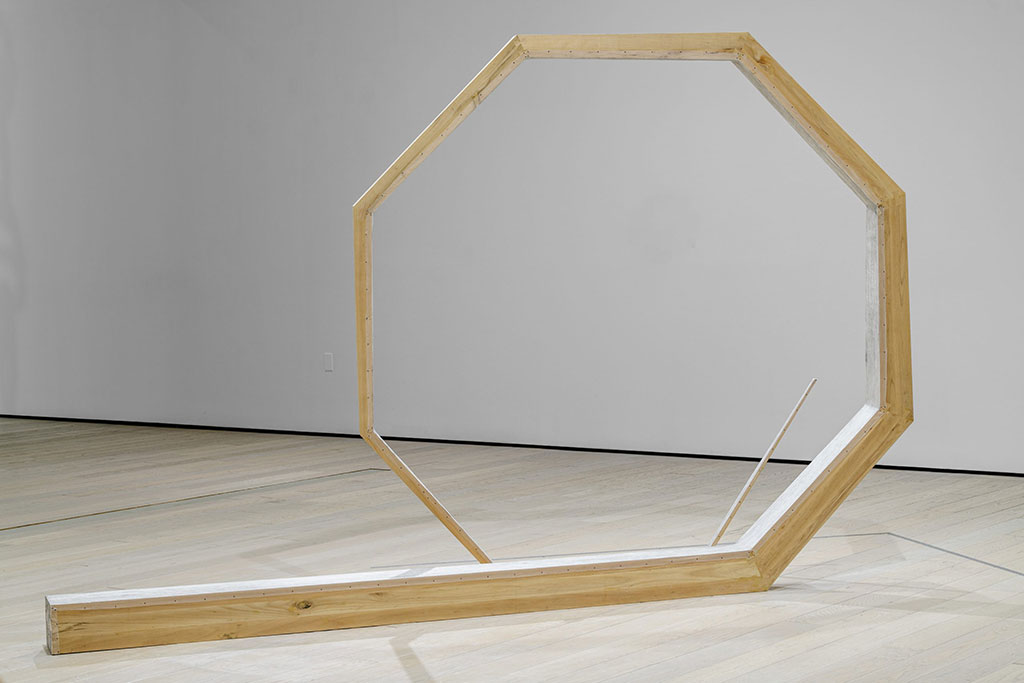

Right: Liu Wei, Merely a Mistake II No. 7, 2013, Doors and door frames, wooden beams, acrylic board, stainless steel, and iron, 480.1 x 190 x 197 cm, The Chu Collection, Photo courtesy of the artist and Long March Space