ART-TRIBUTE:The Allure of Matter-Material Art from China,Part II

Since the 1980s, artists working in China have experimented with various materials, transforming seemingly everyday objects into large-scale artworks. These artists have exploded fireworks into paintings, felted hair into gleaming flags, stretched pantyhose into monochromatic paintings, deconstructed old doors and windows to make sculptures, and even skillfully molded porcelain into gleaming black flames (Part I).

Since the 1980s, artists working in China have experimented with various materials, transforming seemingly everyday objects into large-scale artworks. These artists have exploded fireworks into paintings, felted hair into gleaming flags, stretched pantyhose into monochromatic paintings, deconstructed old doors and windows to make sculptures, and even skillfully molded porcelain into gleaming black flames (Part I).

By Efi Michalarou

Photo: Smart Museum of Art Archive

Too large for a single venue, the exhibition “The Allure of Matter: Material Art from China”, takes up the full gallery footprint of Smart Museum of Art and Wrightwood 659 in Chicago, bringing together 48 two- and three-dimensional works made from a range of unique and humble materials in which conscious material choice has become a means of the artists’ expression, representing this unique trend throughout recent history. Participating Artists: Ai Weiwei, Cai Guo-Qiang, Chen Zhen, Gu Dexin, gu wenda, He Xiangyu, Hu Xiaoyuan, Huang Yong Ping, Jin Shan, Liang Shaoji, Lin Tianmiao, Liu Jianhua, Liu Wei, Ma Qiusha, Shi Hui, Song Dong, Sui Jianguo, Sun Yuan and Peng Yu, Wang Jin, Xu Bing, Yin Xiuzhen, Zhan Wang, Zhang Huan, Zhang Yu, and Zhu Jinshi.

Since the 1990s, Ai Weiwei has utilized several materials that are imbued with tradition, including pottery, porcelain, stone, bronze, and wood. Through his reconfigurations of these materials he often interrogates how cultural value is assigned and accrued. Beginning with his “Furniture” series in 1997, Ai collaborated with expert craftsmen using woodworking techniques developed in the sixteenth century to reconfigure antique furniture into nonfunctional objects. In the work “Tables at Right Angles”, Ai used hidden mortise-and-tenon joints to seamlessly suture together two ancient tables collected from a Beijing antique market. The work was constructed without a single screw or nail. Part of his Furniture series, this work is an example of how Ai alters, transforms, and often destroys cultural relics and historic antiques, subtly questioning the value and authenticity of the tables in their original form and their new worth after being transformed into an art object.

Hu Xiaoyuan gained international attention for her work “A Keepsake I Cannot Give Away” (2005-066), which features delicate silk embroidery. Expanding her material explorations shortly thereafter, Hu had a breakthrough with her 2008 “Wood” series, which juxtaposed silk, wood, and nails. In these works, Hu placed a piece of silk on top of a board and meticulously traced all of the visible wood grain onto the silk. Then, she put the silk aside and covered the wood surface with white paint, obscuring the grain. Finally, she framed the silk over the board using tiny nails, as if stretching a canvas on a wooden frame. Deceptively simple, these finely painted objects require careful scrutiny to uncover the subtle contradictions between representation and reality. In the two geometric sculptures “Ant Bone IV” and “Ant Bone V” Hu employed traditional mortise-and-tenon joints used for centuries in Chinese woodworking and architecture. On each form’s interior, Hu carefully covered the wood with her signature paintings on silk. The interplay between the wood, silk, and nails draws out the tensions between what is hard and soft, real and fake, old and new.

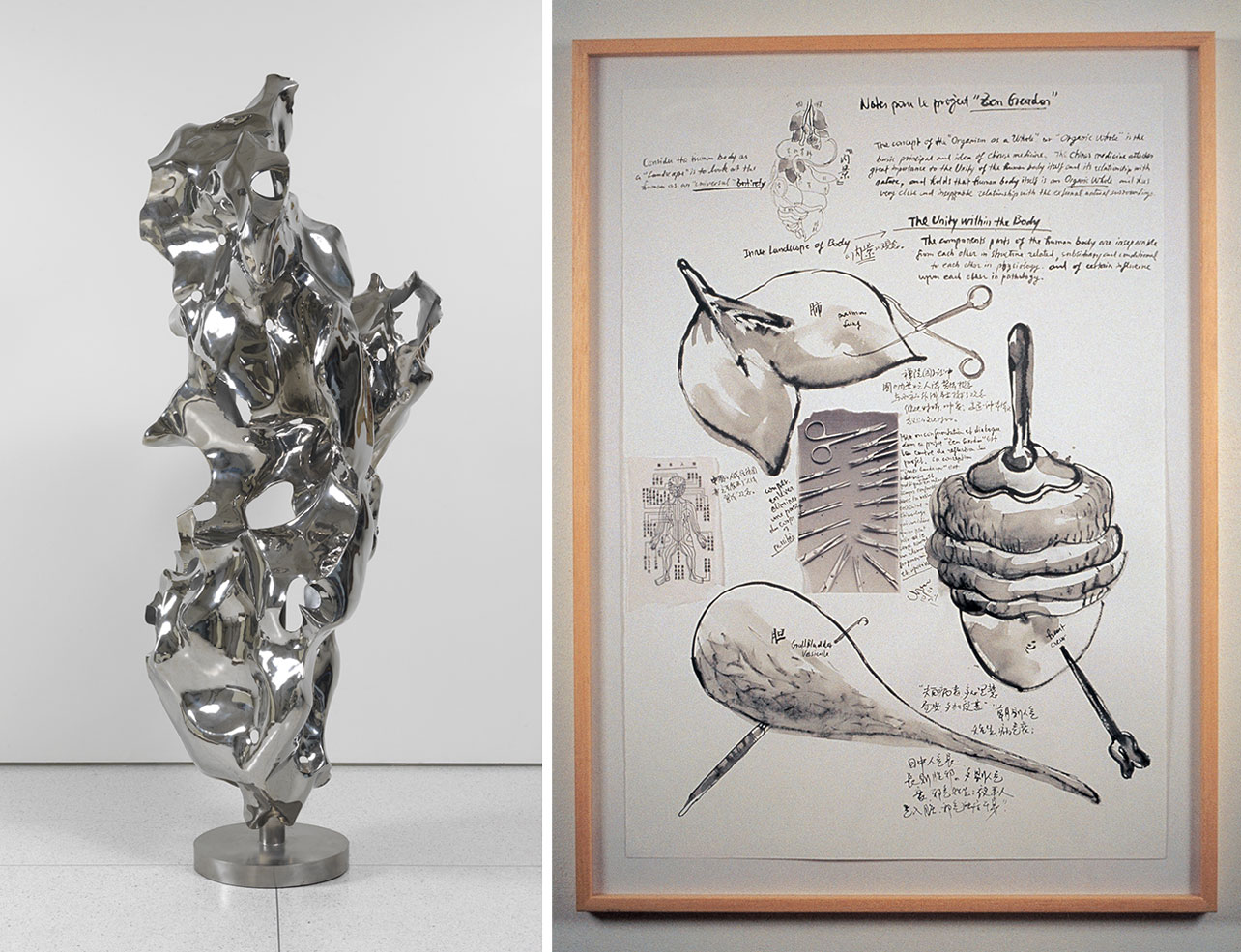

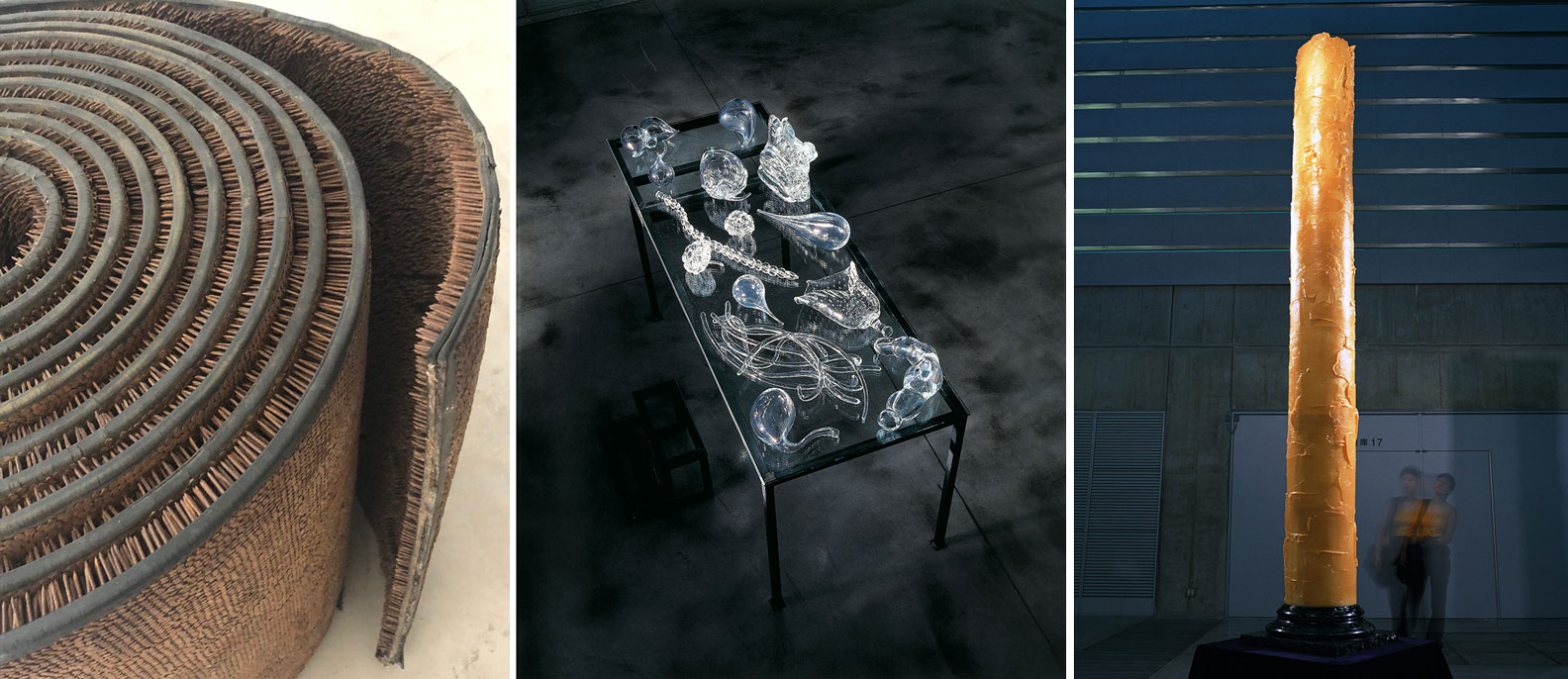

Fascinated with the human body and medicine, the artist Chen Zhen once mused: “When one’s body becomes a kind of laboratory, a source of imagination and experiment, the process of life transforms itself into art”. This interest can be attributed partly to Chen’s family background, both his parents were distinguished doctors, and partly to the hemolytic anemia he began suffering from at the age of 25. Transforming an incurable disease into artistic creativity, Chen experimented with a variety of materials—colored candles and glass in particular—to articulate his own idiosyncratic understanding of the body, which combined Chinese and Western scientific knowledge.The work “Crystal Landscape of Inner Body” evokes the centuries-old Daoist concept of “Internal Alchemy,” a practice of visualizing the human body as a form of healing. In order to initiate a process of purification in the body, one meditates on each internal organ and body part. In “Crystal Landscape of Inner Body”, Chen renders his own internal organs in glistening clear crystal. This purity contradicts the body’s own contamination. It is one of the last pieces Chen created before his untimely death from cancer in 2000.

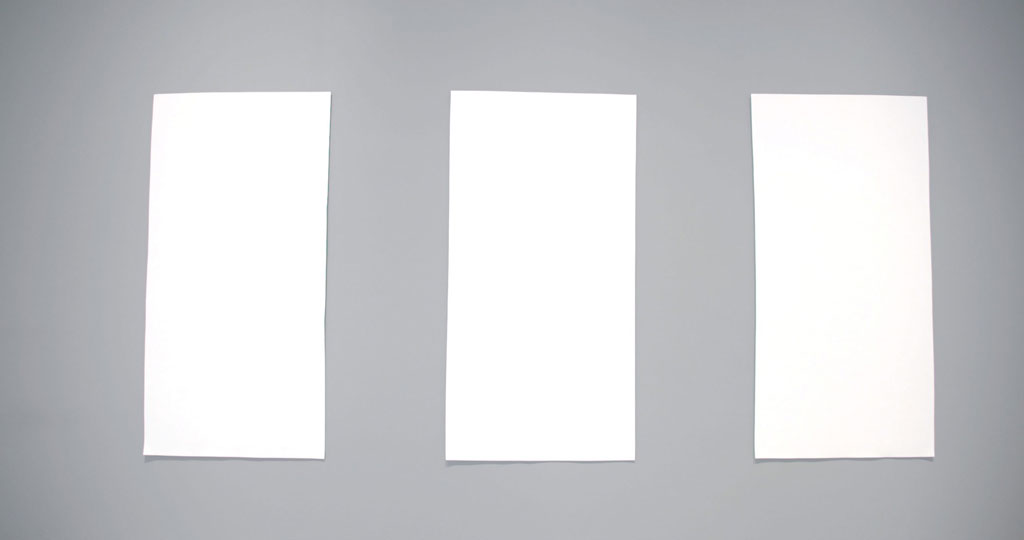

As a teenager, Liu Jianhua was introduced to porcelain by his uncle, a ceramist in the famous porcelain-making city of Jingdezhen. This early exposure was influential: since then the artist has used the pure white clay to produce all of his work. “Blank Paper” and “Black Flame”, two of Liu’s porcelain works featured in this exhibition, explore the characteristics of porcelain and infuse them with a contemporary sensibility. Often displayed in a row on a wall, Liu’s blank porcelain papers simultaneously challenge the viewer’s eyes and mind. Inspired by the unique properties of porcelain, the artist remarked, “Although one can use fiberglass, steel, wood, stone, or any other material to represent a piece of paper, none of them can compete with porcelain that only comes into existence after being fired at over 1,000 degrees Fahrenheit. “Black Flame” consists of eight thousand black porcelain flames that suggest the possibility of a rapidly spreading fire flickering across the gallery floor. The glaze is a key element of this work: its matte shade creates layers of pure blackness. The pool of sharp flames appears menacing; in stark contrast to the calming quality of “Blank Paper”, it is imposing. As a pair, these two works show us the range of emotions that porcelain can elicit, through two very different manipulations of the material.

Coca-Cola was already widely consumed in China by the time He Xiangyu began his first major work of art, “Cola Project” (2008-12). As part of this series He manipulated the soda, subjecting it to physical and chemical (or alchemical) change. For many, Coca-Cola is an icon of Western culture and consumerism, however, He has transformed this ubiquitous product into a medium for artmaking. He’s process consisted of boiling down 60,000 bottles of Coca-Cola in batches, destroying the soda itself in the process, until he was left with desiccated cola-ash. At first, He worked alone, and it took more than six months to boil down one ton of soda. With the help of a crew of migrant workers, all working in a lumber mill outside He’s hometown of Dandong, Liaoning, however, the artist industrialized his process to mass-produce the soda ash. In total, the artist reports boiling down 127 tons of soda.

Since her early childhood, Lin Tianmiao has been fascinated with cotton thread. Her mother would tediously unravel the thread of the white cotton gloves given to workers in state-owned factories to make new clothes and mend others. Lin appropriated this domestic task in the early 1990s, wrapping hundreds of household objects in white thread. For Lin, binding represents a form of corporal punishment that women experience in their daily housework and in domestic labor. In the work “Day-Dreamer”, included in this exhibition, Lin suspends hundreds of cotton threads along the outline of her self-portrait. The haunting silhouette suggests the impact of this labor-intensive process on her body.

One of the most established sculptors working in China today, Sui Jianguo was instrumental in expanding traditional practices of sculpture by embracing new methods and materials, as first seen in his practice during the late 1980s. Sui’s sculptural experiments focused on the tension between inner and outer structure as well as on the juxtapositions between different types of materials such as stone and metal. The sculpture “Kill” is comprised of a single sheet of rubber with 300,000 nails driven through it. The artwork both exposes the incredible resilience of rubber as a material and demonstrates how abstracted forms can manifest broader political significance.

Wang Jin’s many performance and environmental projects since the early 1990s reflect upon the rapid spread of capitalism in China, as well as other social and political issues. Wang’s incisive works comment on the clash and fusion of new and old values by staging ironic combinations of foreign and Chinese symbols. Originally created for one of the first domestic auctions of contemporary art in Beijing in 1997, “A Chinese Dream” faithfully reproduces Peking Opera costumes and imperial robes of the Qing dynasty using translucent PVC plastic sheets. The imperial robes and theatrical costumes levitate like specters of a bygone age. Such garments traditionally bear encoded symbols, such as five-clawed dragons representing the imperial house, or the multicolored waves, rocks, and clouds that present the universe under the ruler’s sway.

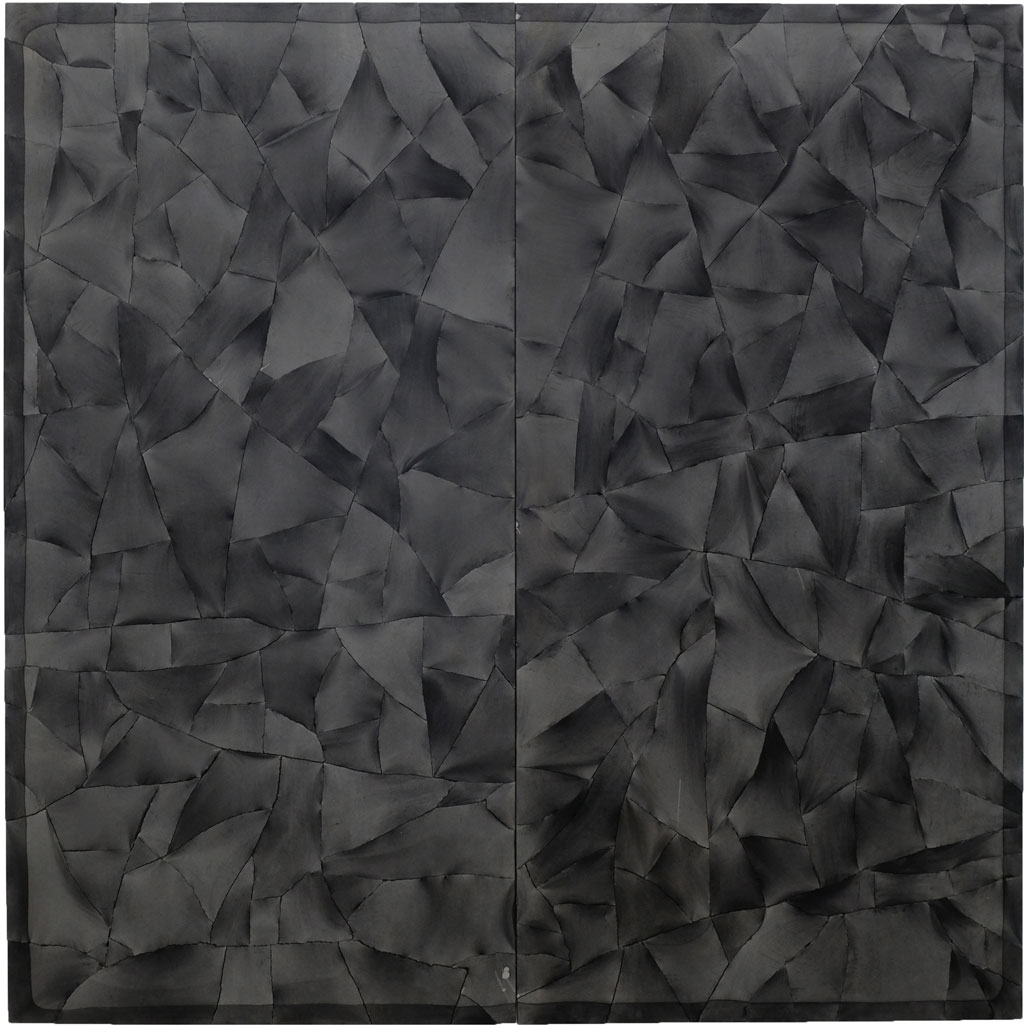

Bridging personal and collective memory, Ma Qiusha’s ongoing work with nylon stockings began from a vivid childhood memory of her mother’s stockings while on her way to school. For Ma, the distinctive thick tan nylon stockings, popular from the 1970s through the 1990s, represented not only her own mother but also an entire generation of women. Collecting decades-old stockings from friends, relatives, and acquaintances, Ma used this “second skin” to cover slabs of broken concrete shards, which are then pieced together into a colorful stone mosaic or fabric tapestry. In “Wonderland: Black Square”, Ma has swapped tan nylon for black stockings, which have only gained popularity in China over the past two decades. Associated mainly with sex workers during Ma’s childhood, this formerly taboo color later became trendy in the early 2000s. The work entices viewers with their subtle and changing sheen, yet hints at a hidden tension between the delicate nylon and the jagged edges of its concrete shards.

Born and raised in Beijing, Yin Xiuzhen grew up in one of the city’s many siheyuan, or courtyard houses, that were demolished during the urban reconstruction efforts conducted in the 1990s. Many traditional houses were removed to make room for gleaming high-rises and new infrastructures. Sensitively reflecting on the transformations around her, Yin produced a number of installations that incorporated the forgotten remnants of such destruction. For “Transformation”, Yin collected 128 cement roof tiles from the thousands that were discarded after the demolition of these siheyuan in her Beijing neighborhood. On each tile, she affixed a photograph documenting the vibrancy of the neighborhood and its changing character. For Yin, these unconventional materials embodied the memories of a place and time period that was rapidly disappearing.

Zhan Wang is renowned for his meticulously made stainless-steel copies of scholars’ rocks. Historically, scholars’ rocks were showcased in Chinese gardens and considered microcosms of the universe. Reflecting upon the rapid economic development and urbanization that characterized China in the 1990s, however, Zhan sought to “update” this traditional object for contemporary society through the use of a modern industrial material—stainless steel. The work “Ornamental Rock” was produced using Zhan’s characteristic method of working with stainless steel. By hammering a pliable sheet of steel across the original rock’s surface, Zhan created a copy that reproduced every minute undulation of the surface of the original. Meant to be placed throughout Beijing’s cityscape, this rock and others like it would have reflected the surrounding skyscrapers, rendering a distorted version of Beijing’s rapidly growing urban fabric upon its surface.

Since the late 1990s, the artistic duo Sun Yuan & Peng Yu has tested preconceptions about what constitutes acceptable artistic materials. Their collaborations, which include the use of live animals, human flesh, bone, and oil, have challenged not only audiences’ physical senses but also their sense of moral propriety. “Civilization Pillar”, commissioned for the exhibition, continues their exploration of materials derived from the human body. Tall, yellow, and gleaming with texture, the work is actually made of human fat that was collected from plastic surgery clinics, then mixed with wax and cast. For the artists, human fat is the physical manifestation of excess: unused food energy stored as deposits on the body. The liposuction process that extracted the fat adds another layer of meaning to the material; excess fat was eliminated through a cosmetic procedure that caters to vanity and modern ideals of beauty. Considering the material to be “a by-product of our contemporary society” the artists display the reclaimed fat as a monument to civilization.

Zhang Huan began using ash as an artistic medium following a visit to the Longhua Temple in Shanghai, where he was struck by the ritual significance of the ash from joss sticks burned for prayers. In “Ash Painting No. 5”, Zhang embedded found black-and-white photographs in the ash-covered canvas, visually representing the hopes and dreams of generations of people. Another series of works rendered Cultural Revolution–era photographs into ash paintings. For “Seeds” the artist’s studio assistants meticulously sorted ash into a palette of varying shades of gray, then reproduced a photograph of collective farming by painting with this ash. The labor-intensive process of creating the work echoes these historic efforts of collective labor, suggesting an ambivalent reflection on both the aspirations and catastrophes of the past era.

Info: Wu Hung and Orianna Cacchione, Smart Museum of Art, The University of Chicago, 5550 S. Greenwood Avenue, Chicago, Duration: 7/2-3/5/20, Days & Hours: Tue & Fri-Sun 10:00-17:00, https://smartmuseum.uchicago.edu & Wrightwood 659, 659 W. Wrightwood, Chicago, Duration: 7/2-3/5/20, Days & Hours: Thu-Fri 12:00-20:00, Sat10:00-19:00, https://wrightwood659.org

Right: Hu Xiaoyuan, Ant Bone V, 2015, Wood, ink, raw silk (xiao), paint, and iron nails, 186.5 x 81 x 191 cm, Courtesy of the artist and Beijing Commune

Right: Chen Zhen, drawing for Zen Garden no. 5, 2000. Collage and India ink on paper, 100 × 70 cm, Collection FREUDE-Turin. Photo courtesy of Galleria Continua-San Gimignano/Beijing/Les Moulins/Havana. © 2019 Artists Rights Society (ARS)-New York/ADAGP-Paris

Right:He Xiangyu, A Barrel of Dregs of Coca-Cola, 2009, Coca-Cola resin, metal, and glass, 210 x 100 x 100 cm, Rubell Family Collection, Miami

Center: Chen Zhen, Crystal Landscape of Inner Body, 2000, Crystal, glass, and metal Table: 95 x 70 x 190 cm, Private Collection-Paris, courtesy of Galleria Continua-San Gimignano/Beijing/Les Moulins/Habana

Right: Sun Yuan and Peng Yu, Civilization Pillar, 2001/2010, Human fat, stearic acid, paraffin wax, petroleum jelly, and metal support, Overall: 370 x 100 x 100 cm, Commissioned by the Smart Museum of Art, The University of Chicago