TRACES: Lawrence Weiner

Today is the occasion to bear in mind one of the central figures in the formation of conceptual art in the 1960s, Lawrence Weiner (10/2/1942-2/12/2021). By translating his work into words, Weiner communicates the content of each work without specifying any of its physical qualities, thus rendering the work objective, accessible, and useful for a diverse audience. This column is a tribute to artists, living or dead, who have left their mark in Contemporary Art. Through documents or interviews, starting with: moments and memories, we reveal out from the past-unknown sides of big personalities, who left their indelible traces in time and history…

Today is the occasion to bear in mind one of the central figures in the formation of conceptual art in the 1960s, Lawrence Weiner (10/2/1942-2/12/2021). By translating his work into words, Weiner communicates the content of each work without specifying any of its physical qualities, thus rendering the work objective, accessible, and useful for a diverse audience. This column is a tribute to artists, living or dead, who have left their mark in Contemporary Art. Through documents or interviews, starting with: moments and memories, we reveal out from the past-unknown sides of big personalities, who left their indelible traces in time and history…

By Dimitris Lempesis

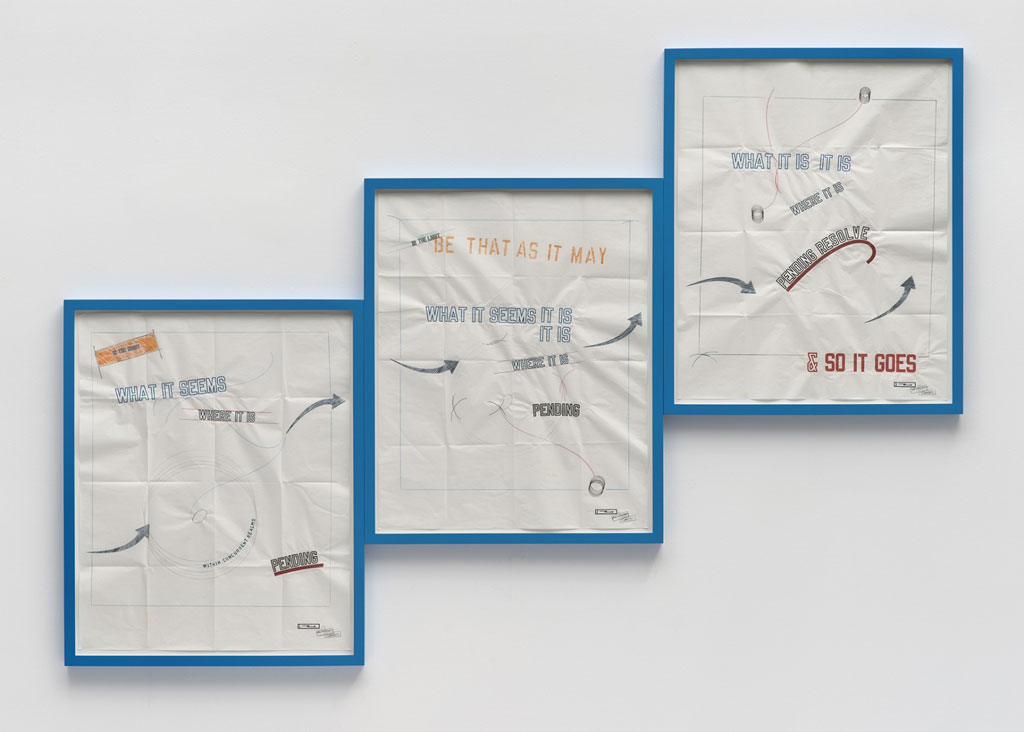

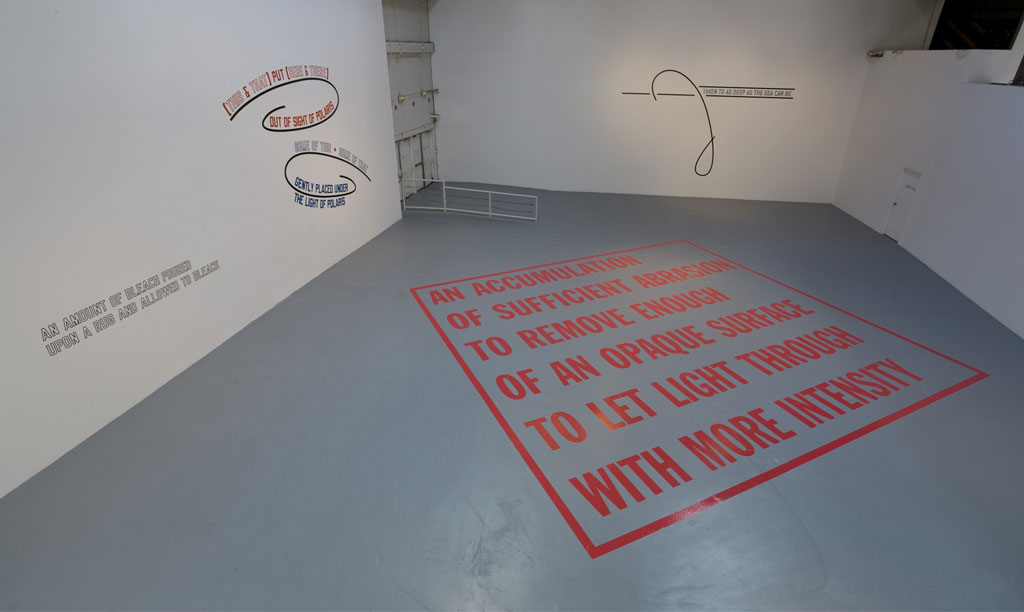

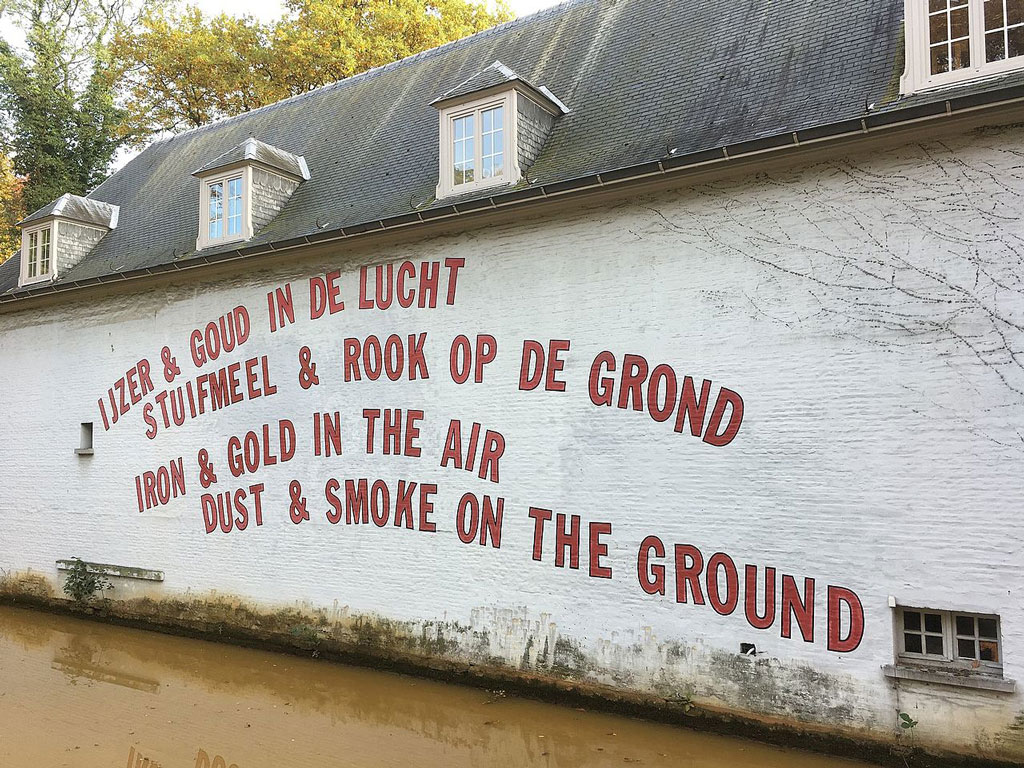

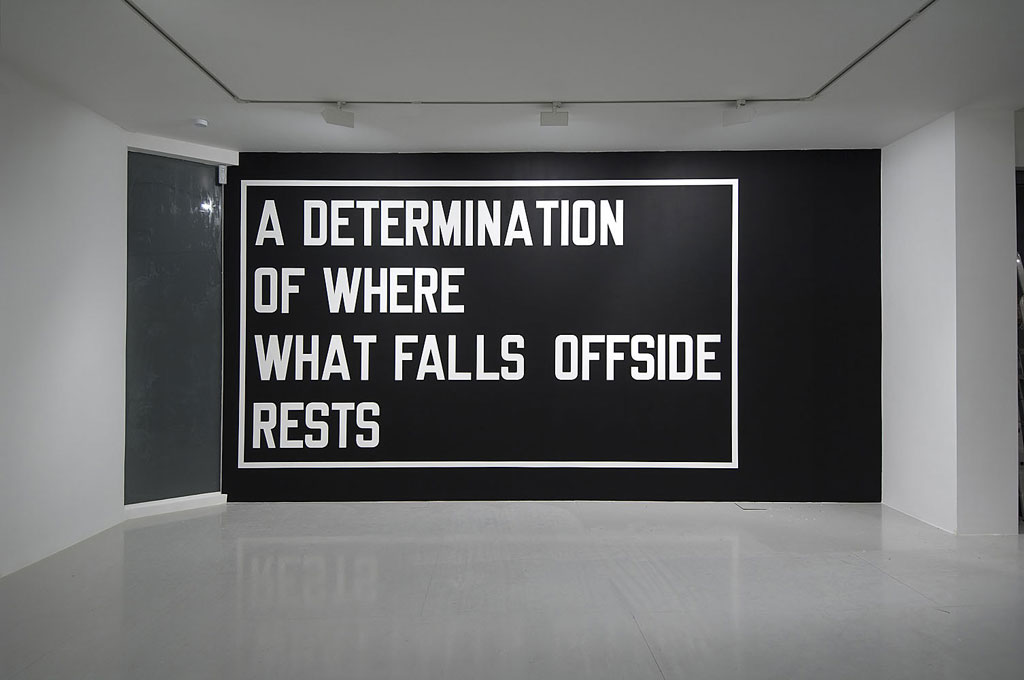

Although self-taught as an artist, Weiner emerged as a leading figure in Conceptual Art gaining international acclaim in the late 1960s. Born in the Bronx, New York, Weiner is best known for his use of language as the primary source for his work. This emerged in 1968, following his earlier experimentations with painting and shaped canvases. His language-based works predominantly take the form of wall installations in galleries, although they have also been spoken as dialogue in video, printed in book format or incorporated into public spaces. In these statements which often focus on materials, actions or processes, Weiner focuses on the interaction between the work and the viewer. After graduating from high school, Weiner had a variety of jobs: he worked on an oil tanker, on docks, and unloading railroad cars. After studying at Hunter College for less than a year, he traveled throughout North America before returning to New York, where he exhibited at Seth Siegelaub Contemporary Art in 1964 and 1965. Weiner’s early work included experiments with systematic approaches to shaped canvases and later, featured squares cut out of carpeting or walls. A turning point in Weiner’s approach came in 1968, when he created a work for an outdoor exhibition organized by Siegelaub at Windham College in Putney, Vermont. Weiner proposed to define the space for his work with rather unobtrusive means: “A series of stakes set in the ground at regular intervals to form a rectangle with twine strung from stake to stake to demark a grid—a rectangle removed from this rectangle”. When students cut down the twine because it hampered their access across the campus lawn, Weiner realized that his piece could have been even less obtrusive: viewers could have experienced the same effect Weiner desired simply by reading a verbal description of the work. Not long after this, Weiner turned to language as the primary vehicle for his work. In 1968, when Sol LeWitt came up with his “Paragraphs on Conceptual Art”, Weiner formulated his “Declaration of Intent” (1968) that: “(1) The artist may construct the piece. (2) The piece may be fabricated. (3) The piece may not be built. [Each being equal and consistent with the intent of the artist, the decision as to condition rests with the receiver upon the occasion of receivership]”. Weiner created his first book “Statements” in 1968, a small 64-page paperback with texts describing projects. Published by The Louis Kellner Foundation and Seth Siegelaub, “Statements” is considered one of the seminal conceptual artist’s books of the era. He was a contributor to the famous “Xeroxbook” also published by Seth Siegelaub in 1968. Both presenting a range of artists associated with Siegelaub’s curatorial practice and utilizing unconventional modes of exhibition, this book marks ongoing attempt by Siegelaub to show work outside of the gallery setting, and his first time showing an exhibition in book form. Furthermore, Siegelaub asked each artist in the exhibition to create 25 pages of work that responded to the photocopy format. Though the Xerox process proved financially unfeasiblethe book continued to be referred to as “The Xeroxbook” preserving its association with the then-new photocopy technology. Participating artists were: Lawrence Weiner, Carl Andre, Robert Barry, Douglas Huebler, Joseph Kosuth, Sol LeWitt and Robert Morris. Weiner’s composed texts describe process, structure, and material, and though Weiner’s work is almost exclusively language-based, he regards his practice as sculpture, citing the elements described in the texts as his materials The wall installations that have been a primary medium for Weiner since the 1970s consist solely of words in a nondescript lettering painted on walls. The lettering need not be done by the Weiner himself, as long as the sign painter complies with the instructions dictated by the artist. Although this body of work focuses on the potential for language to serve as an art form, the subjects of his epigrammatic statements are often materials, or a physical action or process, as exemplified by such works as “ONE QUART GREEN EXTERIOR INDUSTRIAL ENAMEL THROWN ON A BRICK WALL” (1968) or “EARTH TO EARTH ASHES TO ASHES DUST TO DUST” (1970). In others, the subject involves a translation from one language to another or an encounter with a national boundary, as in “THE JOINING OF FRANCE GERMANY AND SWITZERLAND BY ROPE” (1969). In the succeeding decades, Weiner explored the interaction of punctuation, shapes, and color to serve as inflections of meaning for his texts. In 1997, he created Homeport, an interactive environment for the contemporary art web site Adaweb.com, in which visitors can explore a space defined by linguistic rather than geographic features In 2007, he participated at the symposium “Personal Structures Time-Space-Existence” a project which was initiated by the artist Rene Rietmeyer. In 2008 an excerpt from his opera with composer Peter Gordon “The Society Architect Ponders the Golden Gate Bridge” was issued on the compilation album “Crosstalk: American Speech Music: (Bridge Records) produced by Mendi + Keith Obadike. In 2009 he participated in the art project Find Me, by Gema Alava, in company of artists Robert Ryman, Merrill Wagner and Paul Kos.

Although self-taught as an artist, Weiner emerged as a leading figure in Conceptual Art gaining international acclaim in the late 1960s. Born in the Bronx, New York, Weiner is best known for his use of language as the primary source for his work. This emerged in 1968, following his earlier experimentations with painting and shaped canvases. His language-based works predominantly take the form of wall installations in galleries, although they have also been spoken as dialogue in video, printed in book format or incorporated into public spaces. In these statements which often focus on materials, actions or processes, Weiner focuses on the interaction between the work and the viewer. After graduating from high school, Weiner had a variety of jobs: he worked on an oil tanker, on docks, and unloading railroad cars. After studying at Hunter College for less than a year, he traveled throughout North America before returning to New York, where he exhibited at Seth Siegelaub Contemporary Art in 1964 and 1965. Weiner’s early work included experiments with systematic approaches to shaped canvases and later, featured squares cut out of carpeting or walls. A turning point in Weiner’s approach came in 1968, when he created a work for an outdoor exhibition organized by Siegelaub at Windham College in Putney, Vermont. Weiner proposed to define the space for his work with rather unobtrusive means: “A series of stakes set in the ground at regular intervals to form a rectangle with twine strung from stake to stake to demark a grid—a rectangle removed from this rectangle”. When students cut down the twine because it hampered their access across the campus lawn, Weiner realized that his piece could have been even less obtrusive: viewers could have experienced the same effect Weiner desired simply by reading a verbal description of the work. Not long after this, Weiner turned to language as the primary vehicle for his work. In 1968, when Sol LeWitt came up with his “Paragraphs on Conceptual Art”, Weiner formulated his “Declaration of Intent” (1968) that: “(1) The artist may construct the piece. (2) The piece may be fabricated. (3) The piece may not be built. [Each being equal and consistent with the intent of the artist, the decision as to condition rests with the receiver upon the occasion of receivership]”. Weiner created his first book “Statements” in 1968, a small 64-page paperback with texts describing projects. Published by The Louis Kellner Foundation and Seth Siegelaub, “Statements” is considered one of the seminal conceptual artist’s books of the era. He was a contributor to the famous “Xeroxbook” also published by Seth Siegelaub in 1968. Both presenting a range of artists associated with Siegelaub’s curatorial practice and utilizing unconventional modes of exhibition, this book marks ongoing attempt by Siegelaub to show work outside of the gallery setting, and his first time showing an exhibition in book form. Furthermore, Siegelaub asked each artist in the exhibition to create 25 pages of work that responded to the photocopy format. Though the Xerox process proved financially unfeasiblethe book continued to be referred to as “The Xeroxbook” preserving its association with the then-new photocopy technology. Participating artists were: Lawrence Weiner, Carl Andre, Robert Barry, Douglas Huebler, Joseph Kosuth, Sol LeWitt and Robert Morris. Weiner’s composed texts describe process, structure, and material, and though Weiner’s work is almost exclusively language-based, he regards his practice as sculpture, citing the elements described in the texts as his materials The wall installations that have been a primary medium for Weiner since the 1970s consist solely of words in a nondescript lettering painted on walls. The lettering need not be done by the Weiner himself, as long as the sign painter complies with the instructions dictated by the artist. Although this body of work focuses on the potential for language to serve as an art form, the subjects of his epigrammatic statements are often materials, or a physical action or process, as exemplified by such works as “ONE QUART GREEN EXTERIOR INDUSTRIAL ENAMEL THROWN ON A BRICK WALL” (1968) or “EARTH TO EARTH ASHES TO ASHES DUST TO DUST” (1970). In others, the subject involves a translation from one language to another or an encounter with a national boundary, as in “THE JOINING OF FRANCE GERMANY AND SWITZERLAND BY ROPE” (1969). In the succeeding decades, Weiner explored the interaction of punctuation, shapes, and color to serve as inflections of meaning for his texts. In 1997, he created Homeport, an interactive environment for the contemporary art web site Adaweb.com, in which visitors can explore a space defined by linguistic rather than geographic features In 2007, he participated at the symposium “Personal Structures Time-Space-Existence” a project which was initiated by the artist Rene Rietmeyer. In 2008 an excerpt from his opera with composer Peter Gordon “The Society Architect Ponders the Golden Gate Bridge” was issued on the compilation album “Crosstalk: American Speech Music: (Bridge Records) produced by Mendi + Keith Obadike. In 2009 he participated in the art project Find Me, by Gema Alava, in company of artists Robert Ryman, Merrill Wagner and Paul Kos.