ART-TRIBUTE:The Allure of Matter-Material Art from China

Since the 1980s, artists working in China have experimented with various materials, transforming seemingly everyday objects into large-scale artworks. These artists have exploded fireworks into paintings, felted hair into gleaming flags, stretched pantyhose into monochromatic paintings, deconstructed old doors and windows to make sculptures, and even skillfully molded porcelain into gleaming black flames.

Since the 1980s, artists working in China have experimented with various materials, transforming seemingly everyday objects into large-scale artworks. These artists have exploded fireworks into paintings, felted hair into gleaming flags, stretched pantyhose into monochromatic paintings, deconstructed old doors and windows to make sculptures, and even skillfully molded porcelain into gleaming black flames.

By Efi Michalarou

Photo: Smart Museum of Art Archive

Too large for a single venue, the exhibition “The Allure of Matter: Material Art from China”, takes up the full gallery footprint of Smart Museum of Art and Wrightwood 659 in Chicago, bringing together 48 two- and three-dimensional works made from a range of unique and humble materials in which conscious material choice has become a means of the artists’ expression, representing this unique trend throughout recent history. Participating Artists: Ai Weiwei, Cai Guo-Qiang, Chen Zhen, Gu Dexin, gu wenda, He Xiangyu, Hu Xiaoyuan, Huang Yong Ping, Jin Shan, Liang Shaoji, Lin Tianmiao, Liu Jianhua, Liu Wei, Ma Qiusha, Shi Hui, Song Dong, Sui Jianguo, Sun Yuan and Peng Yu, Wang Jin, Xu Bing, Yin Xiuzhen, Zhan Wang, Zhang Huan, Zhang Yu, and Zhu Jinshi.

Working with plastic, meat, and then fruit, Gu Dexin was one of the first artists to use unconventional materials in China. In the early 1980s, Gu melted scrap pieces of plastic he took home from a plastics factory in Beijing where he worked part-time. The resulting abstract forms were a radical departure from his earlier paintings and from the realistic and representational styles of art that dominated the mainstream of artmaking in China at the time. Gu became fascinated by plastic’s texture and versatility. In the untitled room-sized installation featured in this exhibition, Gu assembled a colorful array of contorted, organic, and raw forms made from molded plastic, emphasizing the tactile and versatile nature of the material.

When Gu Wenda first moved to the United States in the early 1990s he began experimenting with different bodily materials. In 1993, he intermingled and felted strands of hair collected from around the world into a large-scale installation. Since then, Gu has continued to use hair as the main material in his ongoing “united nations” series. Conceived as “national monuments” for multiple countries around the world, each monument was composed with hair collected from the local community as its basic material. Shaping the hair with glue into transparent tapestries, on which he would inscribe cryptic pseudo-calligraphic texts using human hair, Gu envisioned that the project would culminate in “a giant wall composed of pure human hair integrated from all of the monuments in the series”. Such a monument would symbolize a utopian world in which all races coexist in a state of natural harmony. For “american code” colorful braids of hair form a tent that encloses a flag, similarly made from hair. By bringing together hair from disparate groups of people from around the world, Gu evokes the United States’ identity as a nation of immigrants. However, the flag hanging in the center of the monument does not belong to any particular country; rather, it is made up of a generic star and stripes formed by pseudo-scripts. By weaving together this common but profoundly personal material, Gu reflects on the relationship between human interconnectedness and distinct personal identities.

Growing up during the decades of drastic urban development that followed the end of the Cultural Revolution (1966–76), Liu Wei became interested in the detritus of urban consumer culture: junked appliances and demolition debris. These scrap materials are commonly found in the demolition sites of traditional middle-class courtyard houses and the construction sites of new high-rises in Beijing. Employing the assistance of local laborers, Liu collected and recycled these materials by hacking them apart with chainsaws, branding them with bold statements, and bolting them together to form colorful sculptural abstractions. Each work from the “Exotic Lands” and the “Merely a Mistake” series features these reused junk materials. Whether hanging on the wall or built up into large-scale architectural structures, the works seem to suggest a futuristic metropolis. Seen again more closely, however, they reveal cuts, peeling paint, nail and screw holes, rot, and broken edges, suggesting the remains of a bygone Beijing.

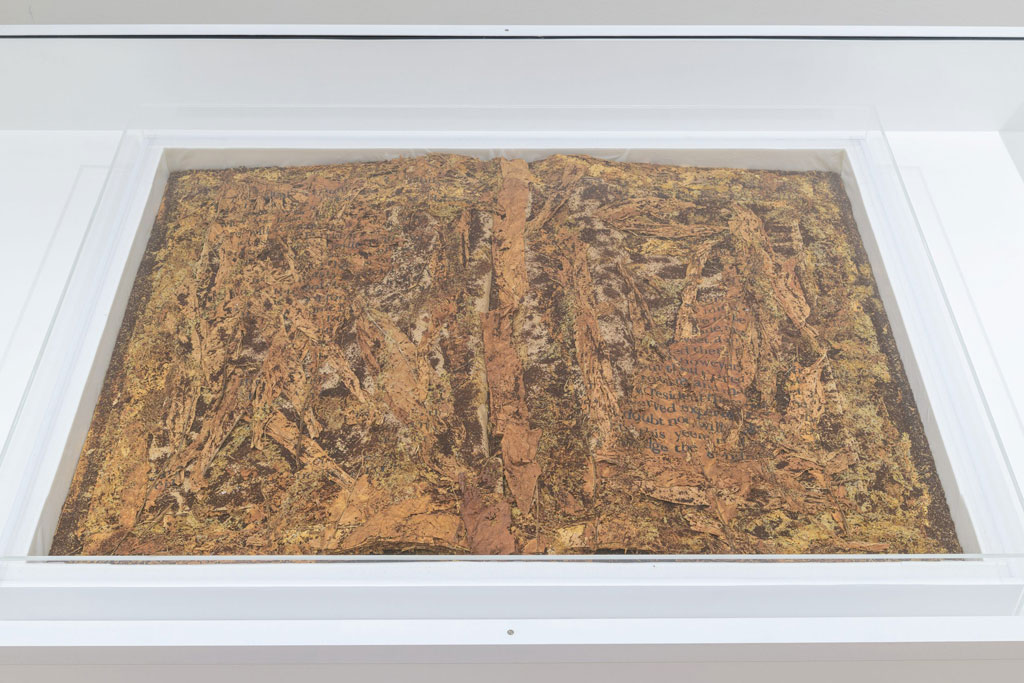

A founder of the Avant-Garde group Xiamen Dada, Huang Yong Ping has famously asserted that the true revolutionary artist must abolish concepts of “art” once and for all. This subversive spirit characterized a number of art experiments the artist conducted, including a series of “book washing” projects begun in 1987. In Huang’s own words: “In 1987, I put the books from the bookshelves in my home into the washing machine and switched it on, then put the entire pulp mixture back onto the shelves”. Huang developed this kind of deliberate destruction as a strategy to disrupt conventional power structures in art production, exhibition, and art history. Huang applied this same “book washing” strategy to create the work “Devons-nous encore construire une grande cathédrale?”. The work was inspired by a historic conversation between the artists Joseph Beuys, Enzo Cucchi, Anselm Kiefer, and Jannis Kounellis, depicted in the photograph hanging on the wall above Huang’s work. Calling for the reconstruction of European culture, Beuys proclaimed, “Now we have to carry out a synthesis with all our powers, and build a new cathedral”. By washing the text that documented this conversation, Huang irreverently destroyed their plans for a new European symbol. The resulting pulped remains of these artists’ collective vision question the validity of such grand historical discourses.

In 1986, Shi Hui was one of the first five artists to work with Bulgarian fiber artist Marin Varbanov at his new Institute of Art Tapestry at the Zhejiang Academy of Fine Arts in Hangzhou. Influenced by his expansive approach to fiber art, Shi has developed a rich body of work over three decades that incorporates materials ranging from cotton, hemp, and silk to wire mesh and paper pulp. Together, Shi, Marin, and others from the Institute catalyzed the rebirth of fiber art in China as an experimental sculptural medium. For the work “Float”, the artist created the horizontal sections suspended in this installation by wrapping and molding sheets of wire mesh, then coating them with the pulp of xuan paper. Used for centuries in ink painting and calligraphy, xuan paper is, for Shi, a material at once imbued with Chinese tradition and completely different from the materials historically used by her European counterparts. However, instead of painting or writing calligraphy on the fine rice paper, she employs the paper as a fibrous material for weaving and sculpting.

One of the most established sculptors working in China today, Sui Jianguo was instrumental in expanding traditional practices of sculpture by embracing new methods and materials, as first seen in his practice during the late 1980s. Sui’s sculptural experiments focused on the tension between inner and outer structure as well as on the juxtapositions between different types of materials such as stone and metal. The sculpture “Kill” is comprised of a single sheet of rubber with 300,000 nails driven through it. The artwork both exposes the incredible resilience of rubber as a material and demonstrates how abstracted forms can manifest broader political significance.

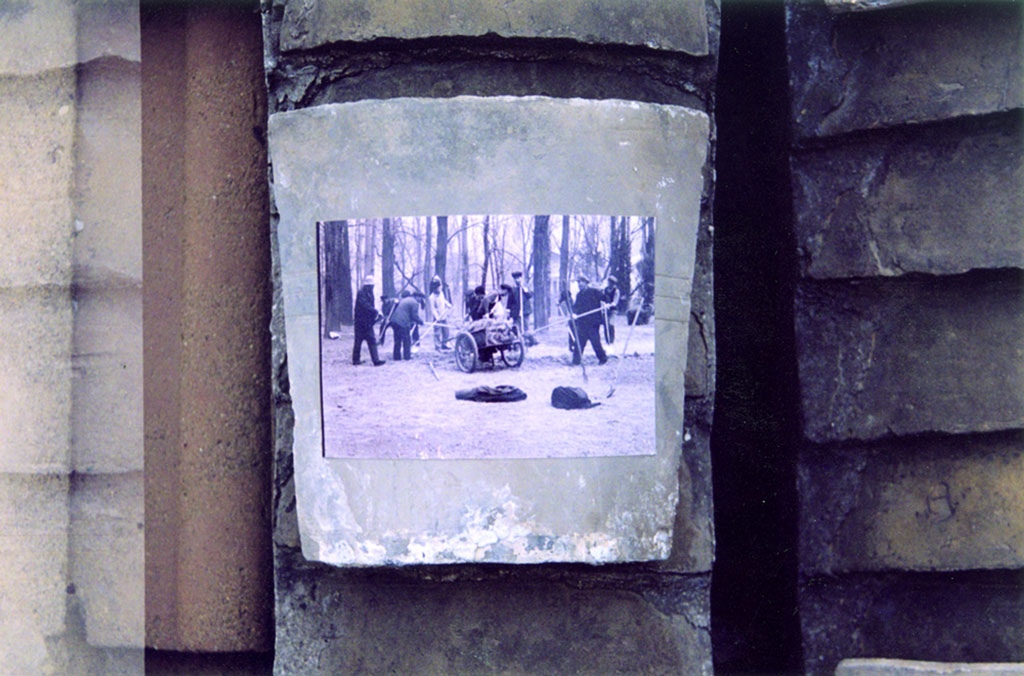

Born and raised in Beijing, Yin Xiuzhen grew up in one of the city’s many siheyuan, or courtyard houses, that were demolished during the urban reconstruction efforts conducted in the 1990s. Many traditional houses were removed to make room for gleaming high-rises and new infrastructures. Sensitively reflecting on the transformations around her, Yin produced a number of installations that incorporated the forgotten remnants of such destruction. For “Transformation”, Yin collected 128 cement roof tiles from the thousands that were discarded after the demolition of these siheyuan in her Beijing neighborhood. On each tile, she affixed a photograph documenting the vibrancy of the neighborhood and its changing character. For Yin, these unconventional materials embodied the memories of a place and time period that was rapidly disappearing.

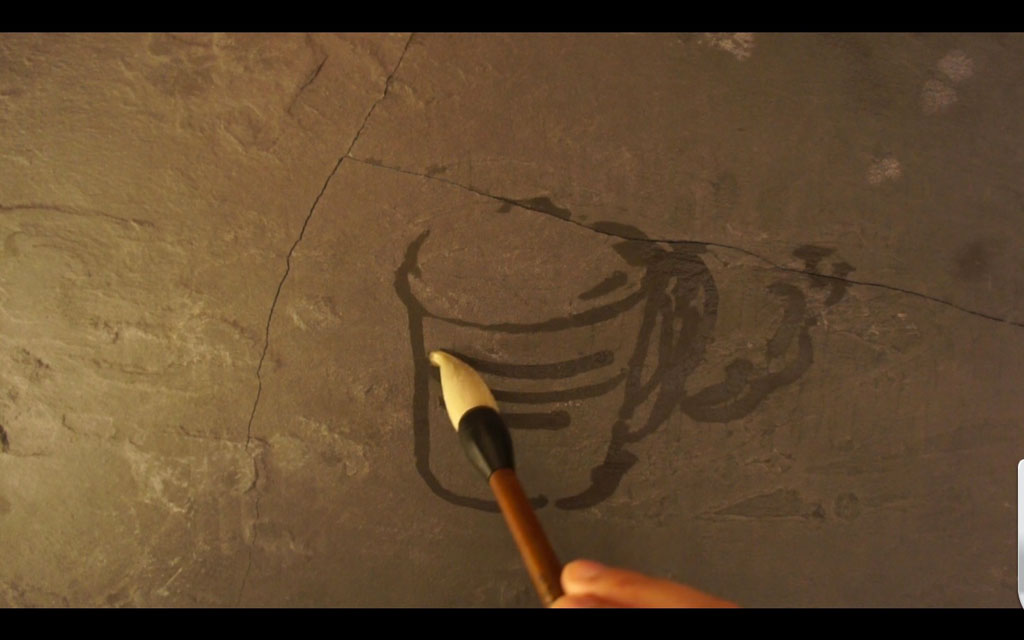

Since the early 1990s, Song Dong has repeatedly used water as a signature material in his practice, which combines performance, video, and conceptual art. “Water Records” draws from the artist’s earliest and ongoing performance work, “Writing Diary with Water” (1995), in which Song kept a daily record of his activities written in water on a dark grey stone. In both works, brushstrokes of written characters and figures begin to evaporate and disappear before the artist can finish delineating them. According to Song, these ephemeral water drawings were meant to be “random fragments of memory, imprecise, incorrect, incomprehensive and incomplete.” By not rendering any concrete, permanent representation, Song’s performance explores the transience of water, a material that leaves no record behind.

In the late 1980s Xu Bing garnered international attention for his formal experiments with the Chinese written script by using the traditional medium of woodblock carving and printing to produce an extensive series of nonsense characters. Since then Xu has expanded this interest to explore the ways in which the written script could bridge different systems of writing and engage audiences across different cultures. Xu’s ambitious “Tobacco Project” (2000-11) combines these various interests. In 2000, during a residency at Duke University, Xu started his research on tobacco, its consumption, and its global circulation. Using tobacco as both material and subject, the artist explores the history and production of the cigarette, global trade, and marketing in his long-term Tobacco Project. Tobacco was one of the first products from the United States to enter the Chinese market. Fascinated by this US-China connection, Xu transformed different aspects of raw tobacco leaves, cigarettes, and cigarette packaging and other marketing materials to explore the interwoven histories of the global economy, commodities, and Chinese art history.

Zhang Yu has been a key figure in developing a dialogue between traditional-style Chinese painting and contemporary art since the early 1990s. The artist’s unconventional use of brush and ink, two fundamental elements of traditional-style painting. Zhang’s “Fingerprint” series is an example of the artist’s novel and conceptual approach to painting. From a distance, the scrolls of this installation appear as if they are made of plain paper, devoid of any pictures or writing. With a closer look, however, the surface texture becomes visible: they are covered with the impressions of thousands of individual fingerprints. Zhang created these impressions by dipping his index finger in water, then tenderly pressing it to the paper’s surface; the spot he touched became wet and darkened slightly, but soon dried, leaving only a subtle, sunken dot. Using neither ink nor brush, Zhang created a series of works that forge a synergetic relationship between painting, installation, and performance with the human body.

Immersing himself in the language of conceptual and material art from the late 1980s onwards, the self-trained artist Zhu Jinshi has produced a wide range of installation works using diverse materials such as bamboo, stone, flour, and iron slabs, as well as readymades including teapots, soy sauce bottles, stretcher frames, Buddha statues, and bicycles. Of these projects, Zhu’s spectacular three-dimensional works, featuring thousands of individually crumpled sheets of “rice paper” or xuan paper, stand out as some of his most successful and well-known works. “Wave of Materials” is composed of xuan paper, a traditional material that has been used by Chinese painters and calligraphers for over a millennium. Zhu sources these sheets of custom-made paper from a rural Chinese paper mill that uses traditional methods to transform elm bark, rice, or bamboo into soft yet textured sheets of xuan paper. To install Wave of Materials each time it is exhibited, Zhu employs a large team to carefully crumple, flatten, and then hang the sheets from the ceiling. In the configuration on view in this exhibition, thousands of these sheets encase or immerse the viewer in a sea of paper intended to provide a meditative encounter. Here, Zhu negates the original function of xuan paper; it can no longer be used as a surface for painting and instead becomes a material in itself.

Zhan Wang is renowned for his meticulously made stainless-steel copies of scholars’ rocks. Historically, scholars’ rocks were showcased in Chinese gardens and considered microcosms of the universe. Reflecting upon the rapid economic development and urbanization that characterized China in the 1990s, however, Zhan sought to “update” this traditional object for contemporary society through the use of a modern industrial material—stainless steel. The work “Ornamental Rock” was produced using Zhan’s characteristic method of working with stainless steel. By hammering a pliable sheet of steel across the original rock’s surface, Zhan created a copy that reproduced every minute undulation of the surface of the original. Meant to be placed throughout Beijing’s cityscape, this rock and others like it would have reflected the surrounding skyscrapers, rendering a distorted version of Beijing’s rapidly growing urban fabric upon its surface.

Throughout her artistic career, Peng Yu has deliberately incorporated provocative materials into her work, ranging from live animals to human flesh, bone, and oil. Peng’s use of the human body, often in collaboration with the artist Sun Yuan, prompts difficult questions on mortality, morality, and ethics. Continuing the exploration of materials derived from the human body, the video “Exile” documents a performance in which the artist poured seven liters of pure human oil (extracted from cadavers) into a polluted Beijing river. Focusing on the water’s oil-coated surface, the video captures the delicate oil-slick patterns that appear on its reflections. For Peng, human fat is a physical manifestation of excessive consumption. By dissolving human fat among the river’s other pollutants, Peng’s performance alludes to the unbridled human impact on the environment.

Info: Wu Hung and Orianna Cacchione, Smart Museum of Art, The University of Chicago, 5550 S. Greenwood Avenue, Chicago, Duration: 7/2-3/5/20, Days & Hours: Tue & Fri-Sun 10:00-17:00, https://smartmuseum.uchicago.edu & Wrightwood 659, 659 W. Wrightwood, Chicago, Duration: 7/2-3/5/20, Days & Hours: Thu-Fri 12:00-20:00, Sat10:00-19:00, https://wrightwood659.org

Right: Sui Jianguo, Kill, 1996, Rubber and iron nails, Dimensions variable; 900.1 x 61.9 cm, Collection of the artist, Courtesy of Pace Gallery