ART-PRESENTATION: Lucio Fontana-On the Threshold

Lucio Fontana is famous primarily for his slashed canvases, but it was not until 1949, after two decades of complete dedication to art, that he used canvas for the first time. The radical gesture he uses to slash his monochrome painting and open it to the absoluteness of space became systematic as of 1958, turning the knife into an instrument to unblock the two-dimensional plane of the painting and imbue it with an almost mystical depth.

Lucio Fontana is famous primarily for his slashed canvases, but it was not until 1949, after two decades of complete dedication to art, that he used canvas for the first time. The radical gesture he uses to slash his monochrome painting and open it to the absoluteness of space became systematic as of 1958, turning the knife into an instrument to unblock the two-dimensional plane of the painting and imbue it with an almost mystical depth.

By Dimitris Lempesis

Photo: Guggenheim Museum Bilbao Archive

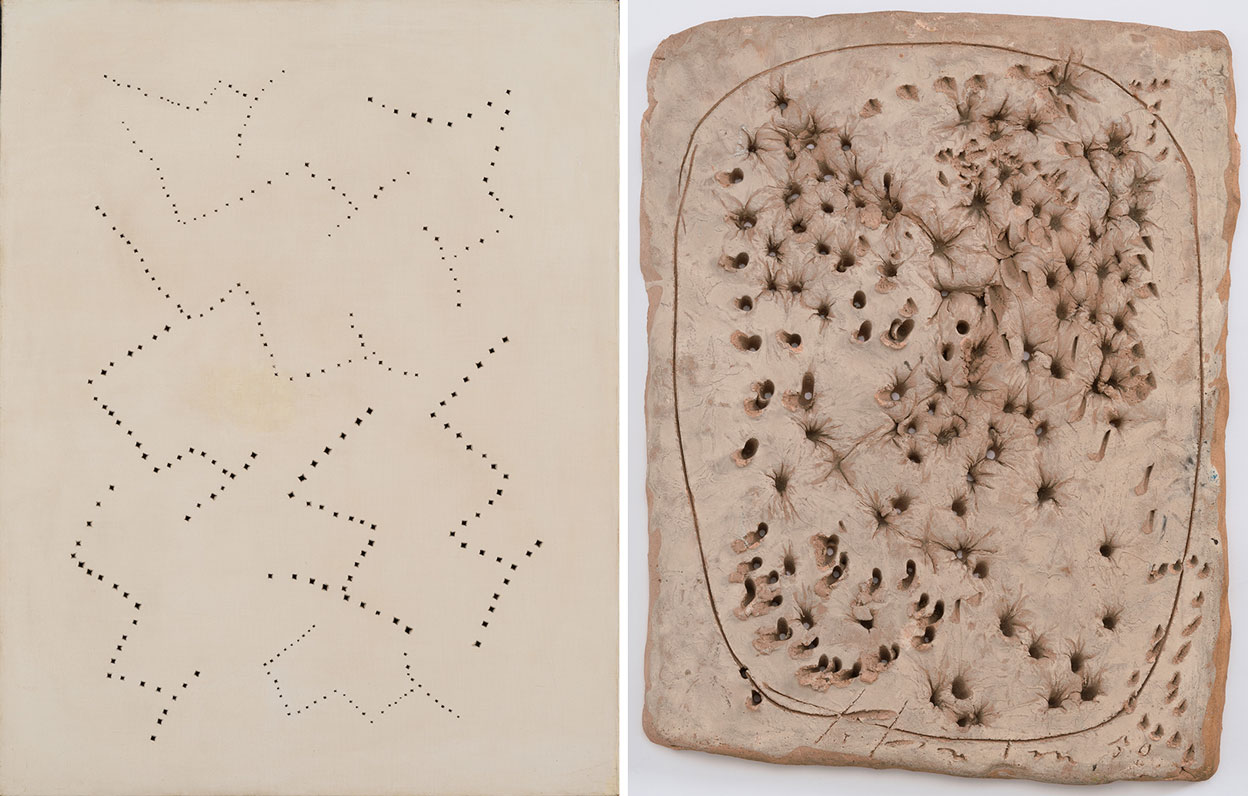

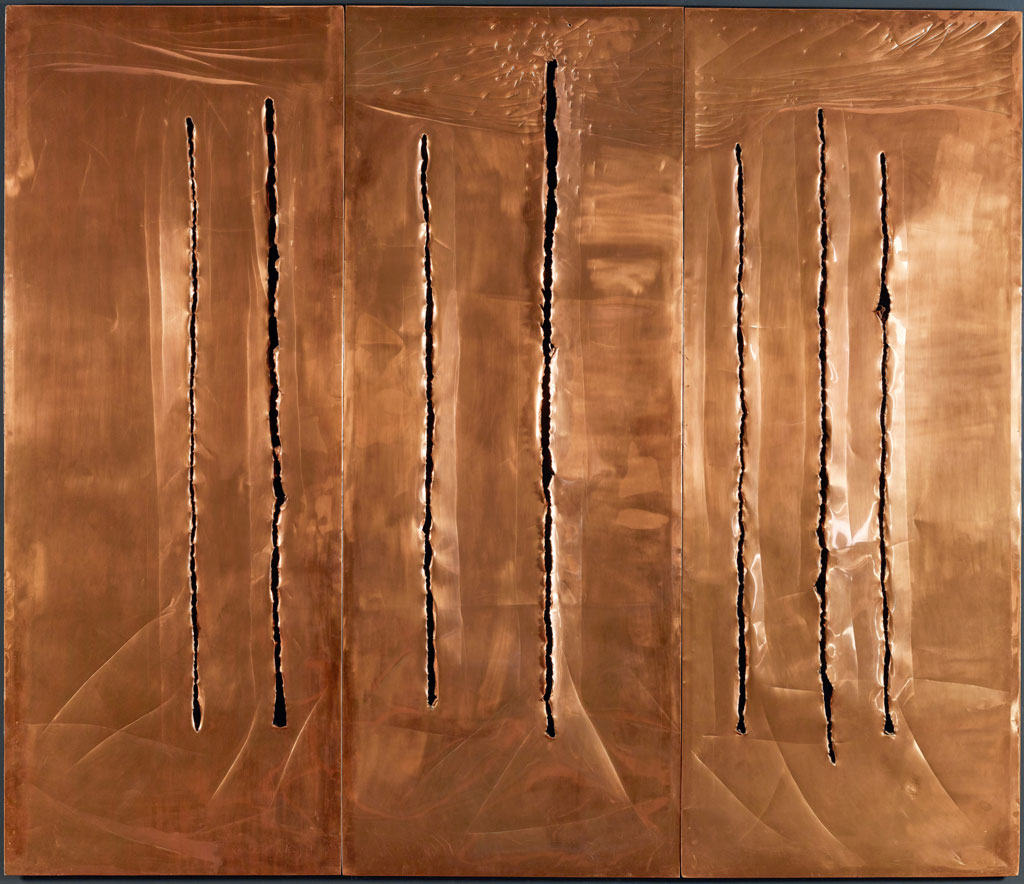

The exhibition “On the Threshold” takes a new look at the legacy of Lucio Fontana, one of the seminal artists of the 20th Century. In a careful selection of close to a hundred works, including sculptures, ceramics, paintings, works on paper and environments created between 1931 and 1968, this exhibition is unfolding a complex, panoramic view, the exhibition situates the radicalism of Fontana’s most iconic series, including the “Cuts” and “The End of God” series, within a context of a career that had a global impact and is still present nowadays. Lucio Fontana began his career as a sculptor in Rosario (Argentina) in the mid-1920s, working in his father’s business, Fontana y Scarabelli, on funerary sculptures for cemeteries in a city that had a large Italian immigrant population. The young artist then moved to Milan to train as a classical sculptor at the Academy of Fine Arts in Brera. He soon showed signs of anti-academic irreverence, preferring to model his sculpture instead of working with the chisel. During the 1930s he developed his career in Italy, focusing on sculpture and relief in plaster, terracotta and ceramic. Fontana adopted a highly expressive, realist and material-based approach, inspired by the Antique sculptures of Etruscan sarcophagi, as can be seen in some of his female portraits, which were sometimes polychromed or gilt. Nevertheless, Fontana was an eclectic artist who absorbed tradition and assimilated avant-garde movements such as Futurism, which helped him maintain a certain aesthetic singularity under the Fascist regime in Italy. In his work with clay, Fontana was able to merge historic genres, subjects and references, while challenging the limits of sculptural practice. In the mid-1950s, Fontana began to use light-reflecting materials such as glitter and fragments of glass in his perforated paintings. To that end, he had large amounts of glass from Murano sent to his studio in Milan, where he shattered it into bits. In the “Pietre” series, Fontana exploited the qualities of glass to project the surface of the painting into the viewer’s space. And the “Olii” series, which the artist started in 1957, present thick areas of impasto which he created by applying broad bands of oil painting directly from the tube with a spatula in order to obtain a brilliant finish. The series and other pictorial cycles of the 1950s are very close to Art Informel, with semi-pictorial and semi-sculptural processes that parallel the ones in his work with modelled clay. In fact, while in Albissola in 1959 Fontana began a series of colored sculptures entitled “Natura”. The artist described those large, rough terracotta balls with holes and slashes as “nothingness or the beginning of everything”. Fontana’s fingerprints, still visible in some of the works from these series, shed light on his physical bond with material. It was in the context of the rebirth of the Italian economy after the War, the Space Race and the growing nuclear threat of the Cold War that Fontana created his most iconic works: the “Cuts”. Breaking the pictorial plane, the radical gesture of the slashes constitutes an act of sabotage to the discipline of painting. Fontana presents the viewer with a form made literally of space. He made his first slashed painting in 1958 and soon refined his technique: he would apply the paint evenly and generously over the canvas, and while it was still humid, slash it with a knife. Once the paint had dried, he would shape the opening with his hands. The last step was to set the opening with a piece of black gauze that he glued to the reverse of the canvas. In 1959, he began a series of paintings in the shape of hexagons, pentagons, circles and other irregular forms. The dynamic surfaces broadened the monochrome field of color of the surrounding space, as in “The Quanta”, small irregularly shaped paintings arranged together on a wall. In “The End of God” series, the “astral eggs” in synthetic colors suggest the idea of an enormous cosmos in an infinite space. Throughout his career, Fontana experimented with reflective surfaces. In his ceramic works of the 1930s, he had exploited the luminous effects of varnish, gold leaf and mosaic, and in his paintings he used fragments of glass, glossy paint, gold and silver. The artist was fascinated by gilding, which had been used throughout the history of art in some of the most refined objects, and whose enigmatic metallic sheen was associated with the divine and the afterlife. Gilding had proliferated during the Baroque period, and became an ever-present element in architectural and ornamental motifs in churches and cathedrals as a result of the Counter-Reformation. After his first trip to New York in 1961, Fontana was inspired by the skyscrapers of Manhattan and began to use materials such as copper, brass and aluminum in the “Metal Sheets” series. The light that falls directly upon these shiny surfaces bounces back towards the observer, flooding the surrounding architecture, while the mirror effect distorts the reflection of the viewer in the work itself. These materials allowed the artist to continue his exploration of the enveloping possibilities of painting, and its depth and physical relationship to the viewer. Through the movement, he called Spatialism, and as author of its “Manifiesto blanco” Fontana sought a synthesis of the arts, and its multi-disciplinary focus broadened the notion of artistic experience to include space in its totality. He was a pioneer of immersive installations, which he called Spatial Environments, and of experiments with electric light and space, including the use of neon tubes. The exhibition includes a reconstruction of the monumental neon arabesque called “Struttura al neon per la IX Triennale di Milano” (1951), as well as two immersive installations exhibited for the first time in Spain: “Ambiente spaziale: “Utopie”, nella XIII Triennale di Milano” (1964) and “Ambiente spaziale a luce rossa“ (1967). These three pieces, conceived through more than 15 years, demonstrate the pioneering nature of Fontana’s experimentations in search of the total work of art. Fontana stands as a pioneer of later immersive developments in contemporary art, where the union of sculpture, light and architectonic space will transcend the traditional division of artistic disciplines.

Info: Curators: Iria Candela and Manuel Cirauqui, Guggenheim Museum Bilbao, Avenida Abandoibarra 2, Bilbao, Duration: 17/5-29/9/19, Days & Hours: Tue-Sun 10:00-20:00, www.guggenheim-bilbao.eus

![Left: Lucio Fontana, Portrait of Teresita (Ritratto di Teresita ), 1940, Mosaic, 34 x 33 x 15 cm, Fondazione Lucio Fontana-Milan, © Fondazione Lucio Fontana, Bilbao, 2019. Right: Lucio Fontana, Olympic Champion (Waiting Athlete) [Campione olimpionico (Atleta in attesa)], 1932, Painted plaster, 121 × 92 × 70 cm, Collezione d’Arte e di Storia della Fondazione Cassa di Risparmio-Bologna, Italy , © Fondazione Lucio Fontana, Bilbao, 2019](http://www.dreamideamachine.com/web/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/0614.jpg)