ART-PREVIEW: Rosemarie Castoro-Wherein Lies the Space

Across her career Rosemarie Castoro attempted and experimented with almost every mode of art imaginable. She developed her oeuvre in the Minimalist, post-Minimalist and Conceptual contexts. One of the few women associated with Minimalism, she broke the artistic boundaries of the time by introducing surreal and sexual allusions into the rigor of Minimalism. In fact, she playfully rejected the term “Minimalist” in relation to her own work, stating in 1986: “I’m not a Minimalist, I’m a Maximust!”.

Across her career Rosemarie Castoro attempted and experimented with almost every mode of art imaginable. She developed her oeuvre in the Minimalist, post-Minimalist and Conceptual contexts. One of the few women associated with Minimalism, she broke the artistic boundaries of the time by introducing surreal and sexual allusions into the rigor of Minimalism. In fact, she playfully rejected the term “Minimalist” in relation to her own work, stating in 1986: “I’m not a Minimalist, I’m a Maximust!”.

By Dimitris Lempesis

Photo: Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac Archive

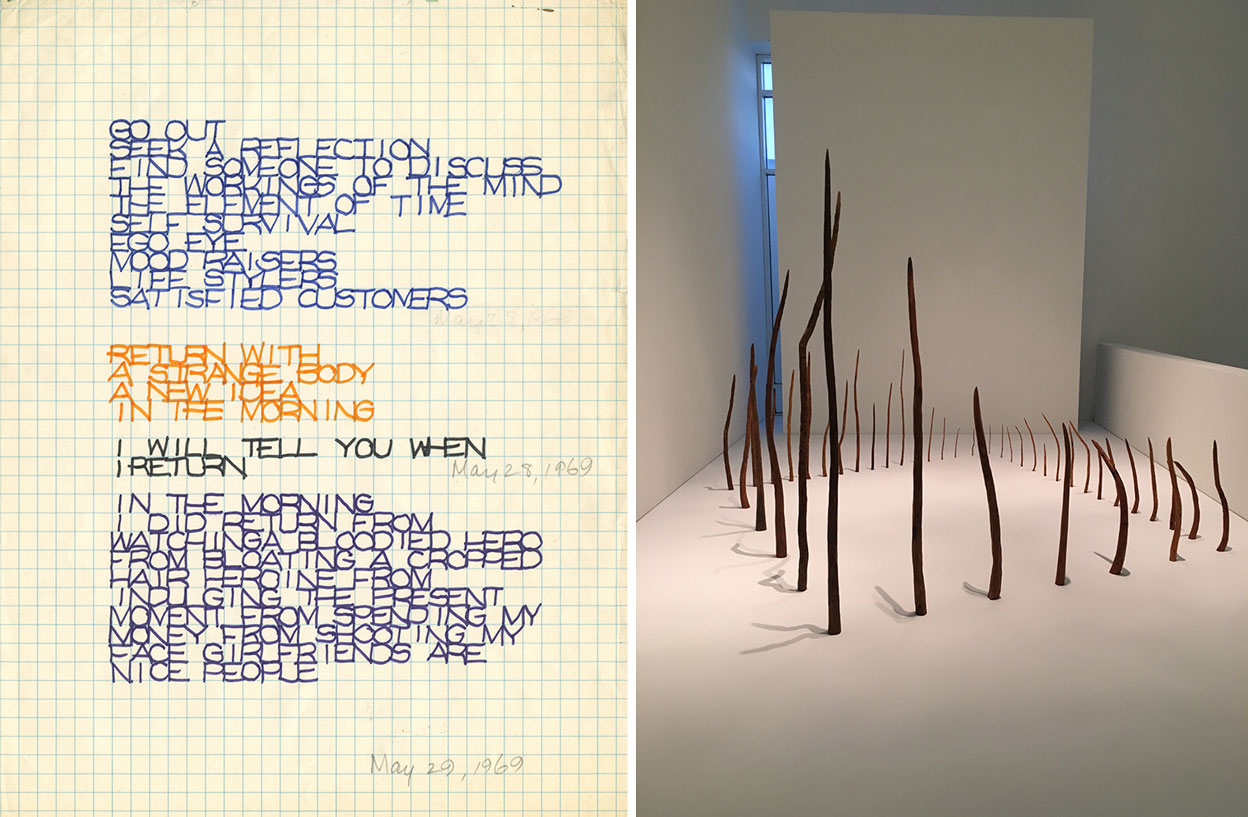

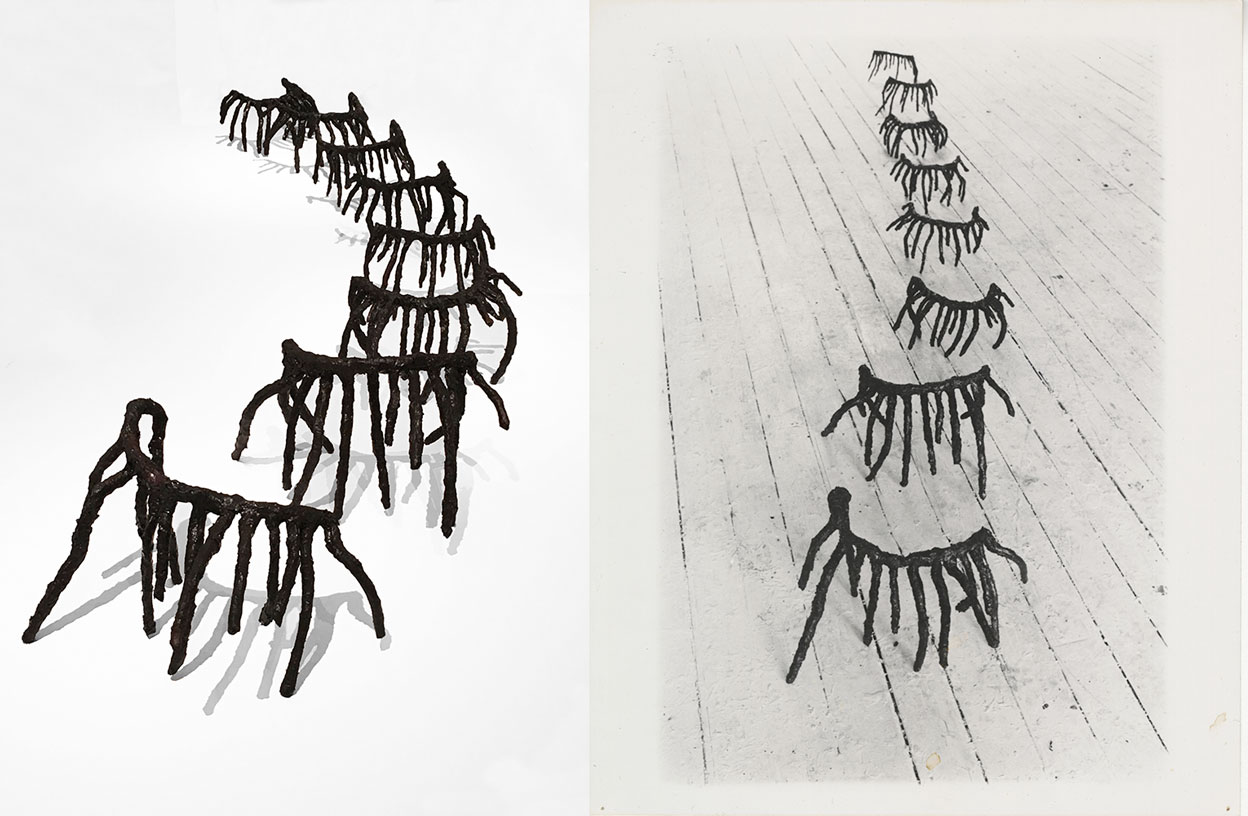

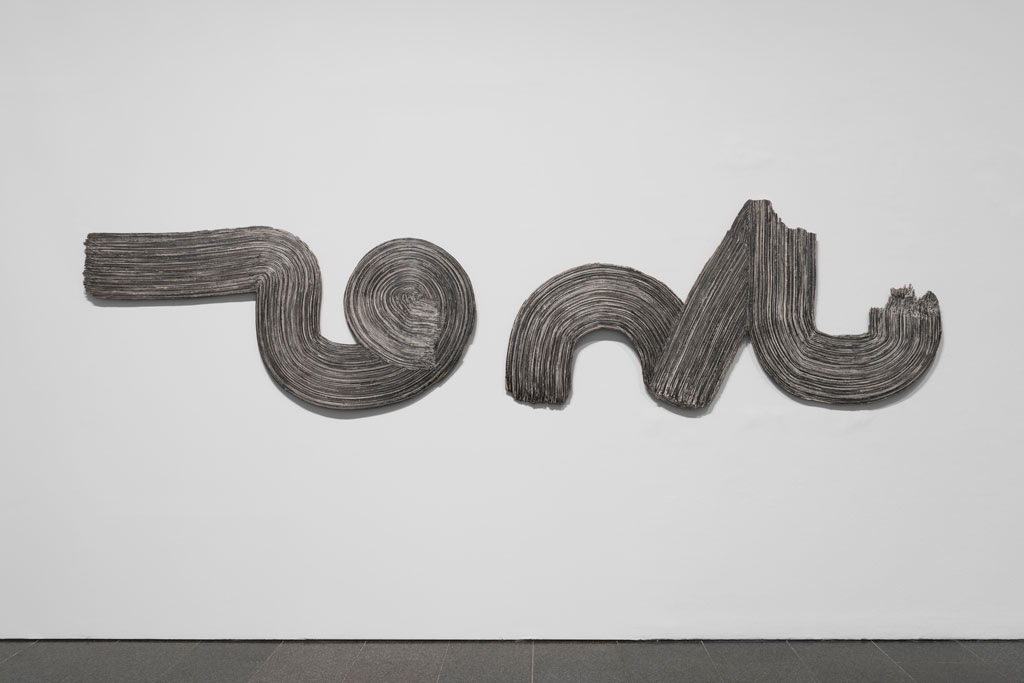

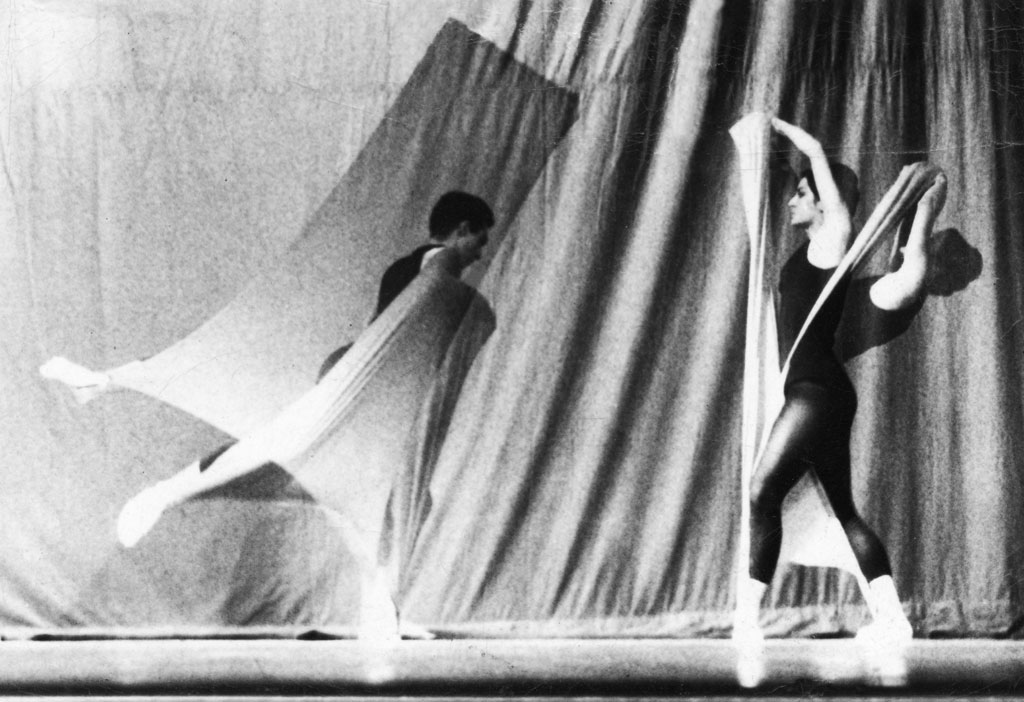

The exhibition “Wherein Lies the Space” encompasses all aspects of Rosemarie Castoro’s multi-faceted practice, spanning the mid-1960s to the mid-1980s. Presenting seminal pieces from each of her distinctive bodies of work, this survey exhibition explores her pivotal contribution to the development of abstract painting, sculpture, conceptual drawing, concrete poetry and performance. From her early paintings, which led Frank Stella to proclaim her among the greatest colorists of their time, to her monochrome gestural wall works and the large-scale organic sculptural forms that became her hallmark, Castoro’s work, overshadowed by that of her male peers. Rosemarie Castoro was a central figure of the New York art scene in the 1960s, together with her then-husband Carl Andre, and her Soho loft studio became a hub for Sol Lewitt, Richard Long, Lawrence Weiner, Lee Lozano, Michael Heizer, Robert Smithson, Seth Siegelaub and other protagonists in the tightly knit scene of the time. Throughout her life she showed a tendency to blend media – declaring herself a “paintersculptor” and her work was pioneering across disciplines. Born in Brooklyn, to an Italian-American family, Castoro lived and worked in New York her entire life. In the late 1950s, she began studying art at Pratt Institute and joined the New Dance Group, where she trained as a dancer and in choreography. While still a student, she met the experimental filmmaker Hollis Frampton and the artist Carl Andre, whom she married in 1963 (they divorced in 1970). Castoro began her career with graphic design, which accounts for the persistent importance of drawing in her work. Once she had graduated from Pratt, she found little opportunity to choreograph and painting offered the chance to develop her own ideas and an independent art practice. Her earliest mature works from 1964–65 were paintings executed on square format canvases first in painterly tessellated “Y” shapes and later as geometrically rendered “Y”s against a monochrome ground, the minimal composition having the potential for infinite repetition (the first manifestation of a theme of infinity in Castoro’s work). The paintings are characterized by bold literal color in diverse, opposing or close color contrasts, her colorism attracting the praise of painter Frank Stella. Castoro developed a friendship with the painter Agnes Martin, whose influence might be detected in these early minimal paintings through their precise execution and visible pencil drawing. As Castoro’s painting developed, she fractured the “Y” shapes into bars, distributing them as an all-over pattern: either in seemingly chaotic, chance compositions; in discrete though overlapping groupings; or else graphically regimented. While the “Y” figure might be seen as standing in for the body, the anthropomorphic analogy can be continued in considering the bars as either bodies or demarcations of feet. The relation of painting to dance is revealed through a consideration of bodies within space and their graphic rendition in minimal dance notation. From 1966, Castoro’s painting began to emphasize the seemingly random and irregular geometric forms created from the superimpositions or ‘interferences’ of one ‘bar’ over another. These works explore subtle and intermediate color tonalities and close contrasts that, with their formal organization, heighten the optical qualities of the works. Such work was included in the 1966 group exhibition “Distillation” curated by E. C. Goossen at the Stable and Tibor de Nagy Galleries, New York, one of two exhibitions curated by Goossen that helped to define Minimalism as a movement. Two series of paintings of the later 1960s indicate Castoro’s increasing use of systems and her move towards Conceptual Art. Near-monochrome abstractions, the Inventory paintings emulate her drawing practice by employing diagonal lines to record the measurements of space or an encounter with an artist friend, as in “Portrait of Sol Lewitt with Donor and Friends – Oct 3, 1968”. Another complementary series are her prismacolor works executed in pen through which Castoro built up surfaces of densely repeated lines. The importance of line, implicit in the visible under-drawing of her earlier works, comes to the fore in these paintings. For a little more than two years, Castoro departed from painting and produced conceptual art in a diverse range of other media, including performance art actions enacted in both street and studio, concrete poetry and installation art. These works reveal the intersection of a concern with time and space in her work. This period also saw her involvement in activism through the Art Workers’ Coalition, which met in her studio at 151 Spring Street. Her most overtly political work, the concrete poem “A Day in the Life of a Conscientious Objector” (1968–69) was shown as a slide and audio installation at Dwan Gallery in 1969 and indicated her tendency towards intermedia. Castoro wrote a poem each day for one hour, beginning an hour later each day, over a period of 24 days. The work is a complex reaction to a fraught moment in the history of the U.S.A. Despite this political engagement, Castoro rejected becoming closely involved in feminism, which she saw as restrictive and a form of “segregation”. She also created a series of “stopwatch” works recording her everyday routines and the duration of each task, exhibiting an obsessive attention to time. In 1969–70, Castoro participated in three exhibitions curated by Lucy Lippard and a series of single-day events of street-based actions collectively titled “Street Works”, which occurred on select days from March to December 1969. In 1970, Castoro developed freestanding panels that occupied the space of the spectator. The surfaces were created from gesso applied with a broom and then covered in graphite hatching so that the works combine painting, sculpture and drawing. Castoro’s statement “my panels are my containers” makes clear their relation to the body. These works are further reinforced as settings for the body by the numerous photographs she took and pasted into her journals, which show Castoro adopting dance-like poses within them or performing with ropes suspended in front of them. The freestanding panels attain an almost architectural scale and character, which, while maintaining an origin in painting, moves her work closer to that of Minimalist sculpture. They were shown in 1971 in Castoro’s first solo gallery exhibition. A year later, she exhibited a second series along with reliefs of isolated brushstrokes. In the 1970s, she created post-Minimalist sculptures from epoxy with dark, painterly surfaces, often suspended from the ceiling, including the large installation “Land of Lads” (1975). The white background threw such works into sharp relief and revealed their continuing relation to drawing by highlighting their organic line. From the mid-1970s, Castoro began making works from wood: first as ephemeral landscape interventions, which she described as a “sculptural drawing” even though it references dance, and later as gallery works. She worked on large structures of spiky installations made of carved bare wood trunks, such as the iconic “Beaver’s Trap” (1977) titled after the English translation of Castoro’s Italian family name. The piece consists of 42 wooden stakes aligned on the perimeter of a square. They are arranged so that the tallest stake, about 2 m-high, stands at one corner of a rectangle, which is formed by the remaining stakes generally descending in height to the shortest, about 30 cm, at the opposite corner. She also made robust installations for urban settings such as “Trap-a-Zoid” (1978). These works address perception through perspective and heightened recession, a recurrence of the theme of infinity in Castoro’s work. Towards the end of the decade, she began an extended series of sculptures called Flashers, implying bodily exposure. Throughout her later career Castoro maintained her engagement with various art forms, including dance. She also continued her activism, helping to found the HIV Arts Network (HAN). She passed away in 2015.

Info: Curator: Anke Kempkes, Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac, 7 rue Debelleyme, Paris, Duration: 22/2-30/3/19, Days & Hours: Tue-Sat 10:00-19:00, https://ropac.net