ART-PRESENTATION: Art Brut From Japan, Another Look

Art Brut is a French term invented by Dubuffet to describe art which is made outside the academic tradition of fine art. Jean Dubuffet saw fine art as dominated by academic training, which he referred to as cultural art. For Dubuffet, Art Brut, which included graffiti, and the work of the insane, prisoners, children, and primitive artists was the raw expression of a vision or emotions, untramelled by convention. He attempted to incorporate these qualities into his own art, to which the term art brut is also sometimes applied.

Art Brut is a French term invented by Dubuffet to describe art which is made outside the academic tradition of fine art. Jean Dubuffet saw fine art as dominated by academic training, which he referred to as cultural art. For Dubuffet, Art Brut, which included graffiti, and the work of the insane, prisoners, children, and primitive artists was the raw expression of a vision or emotions, untramelled by convention. He attempted to incorporate these qualities into his own art, to which the term art brut is also sometimes applied.

By Efi Michalarou

Photo: La Collection de l’Art Brut Archive

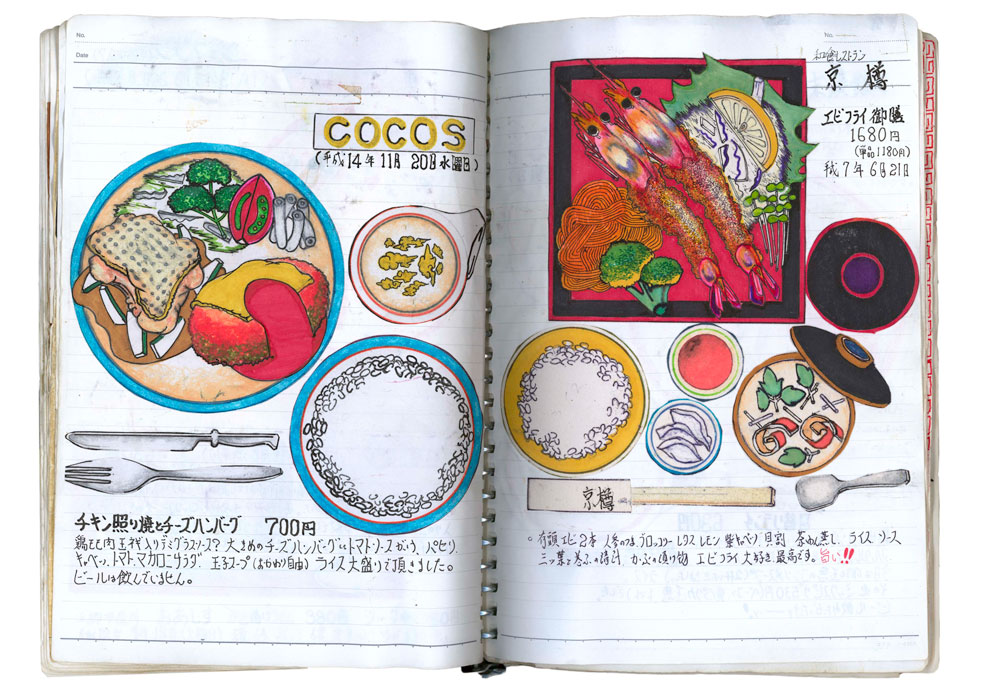

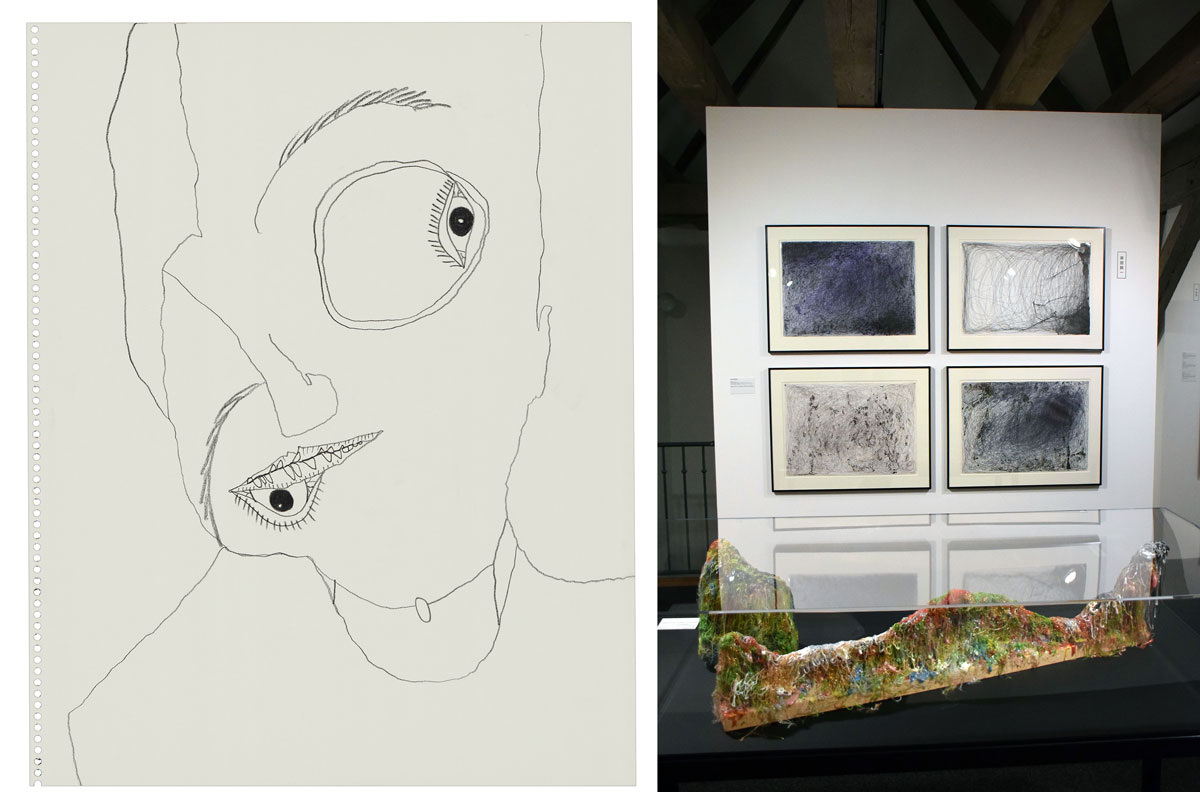

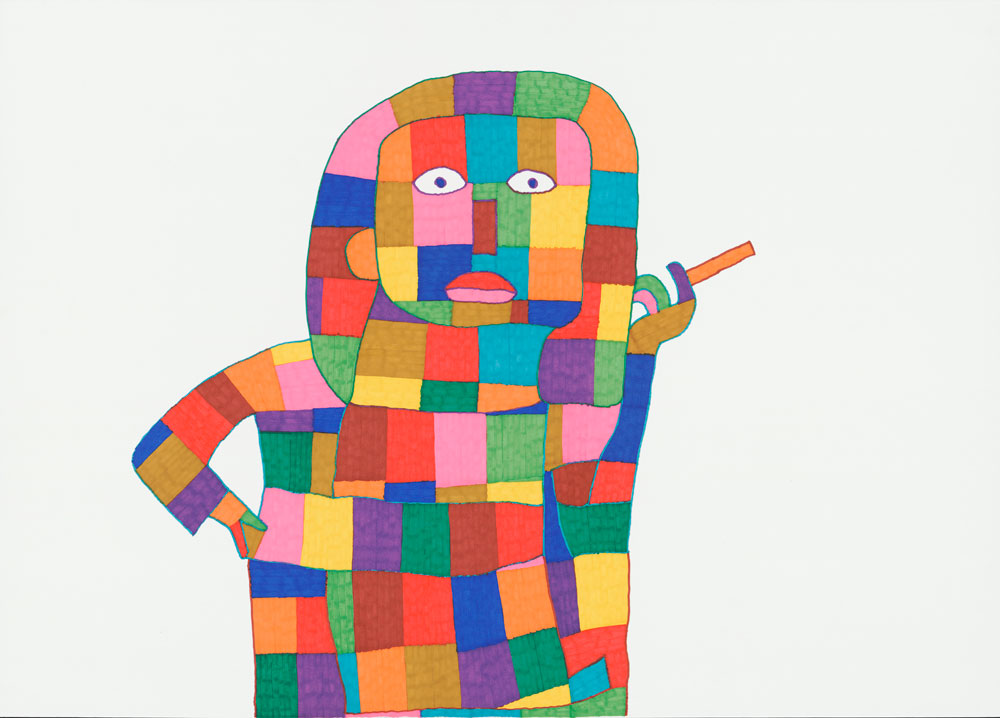

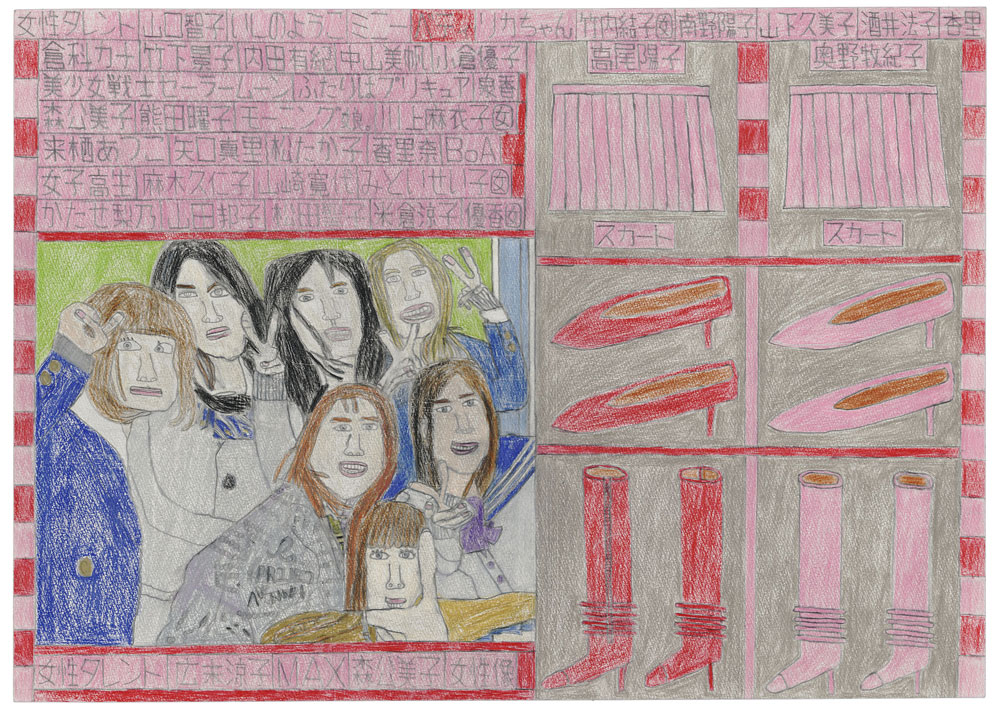

The exhibition “Art Brut From Japan, Another Look” features works by 24 Art Brut creators who are working in Japan today. It comes as a follow-up to “Art Brut from Japan”, the first-ever exhibition of this kind of art outside Japan, which was presented at the Collection de l’Art Brut in 2008. As the phenomenon of Art Brut has become better known within Japan, the works of local creators have gained media attention there, but misunderstandings about the history and nature of this kind of art also have emerged among the general public. At the same time, because very little market infrastructure exists in Japan for the sale and distribution of works made by Japanese creators of Art Brut, direct access to this kind of art has been limited. Art lovers outside Japan have found it difficult to acquire their works. Since 2013, Momoka Imura has participated in the art-making program at Yamanami Kōbō, an art workshop for disabled persons in Shiga Prefecture. At her worktable in Yamanami Kōbō’s fabric-arts building, Imura is surrounded by buckets filled with plastic buttons and by her finished pieces or works-in-progress. Her humble tools and materials include fabric swatches, buttons, thread, needles, and scissors. With these items, she creates brightly colored, round fabric blobs. Each object is made up of several sheets of button-covered fabric. Imura starts by covering one piece of fabric with buttons and then forming it into a ball, which she encases in another piece of button-covered fabric. She repeats this process until arriving at a point at which a multi-layered ball or blob feels finished. Itsuo Kobayashi lives with his elderly mother in Saitama Prefecture, northeast of Tokyo. In the past, he worked at a restaurant until, in his mid-forties, suffering from complications related to neuritis, he found it difficult to walk. Kobayashi withdrew from the working world and devoted his energy to the deeply personal art he had begun making many years earlier. Fascinated by food, when he was younger, Kobayashi started filling notebooks with detailed illustrations and descriptions of every meal he had ever eaten. To this day, he continues documenting his meals in this thorough, almost scientific manner. In recalling each past meal, Kobayashi mentions the name of the restaurant from which he purchased take-out food or at which he dined. Demonstrating the remarkable power of his memory, he describes the design of the plates, the décor, and the ambiance of each of the restaurants he has visited, and analyzes the flavors and ingredients of the dishes he has tasted. Watching Toshio Okamoto at work is like watching a performance. Lying on the floor of his studio, he stretches and gesticulates, with one arm tucked behind his head as he dips a chopstick) in black ink before making a stroke on a large sheet of paper. Okamoto’s marks appear to be both deliberate and spontaneous, giving the images he creates a dynamic, urgent character. Listening to music as he works, Okamoto tends to begin by making a rough sketch of his subject, on top of which he adds many overlapping layers of lines and splattered ink. Sometimes his pictures are almost silhouettes, featuring jet-black figures. In other works, he skillfully uses gradations of tones to suggest volumes, textures, and movement. With their high-contrast, black-and-white palette, vigorous strokes, and intense character, Okamoto’s drawings bring to mind the psychologically charged works of the German Expressionists of the early 20th century. Takuya Tamura usually depicts people and their everyday gestures or poses, but sometimes he draws animals, too. Using a grid of bold, multicolored squares set against plain, white backgrounds, Tamura stylizes his subjects and their expressions, remarkably capturing a sense of their emotions or individual personalities. To make his images using marker pens on paper, Tamura starts with a simple outline of his subject, which he then fills in with his signature, multicolored checkerboard motif. His colors are bright — orange, red, pink, blue, green, purple. Thanks to the consistent color values of each of the colors in his palette, even his browns look bright and energetic. Their big, poster-size presentation accentuates Tamura’s instinctive, strong sense of composition and his innate understanding of design. Yasuyuki Ueno, who takes part in the workshop at Atelier Corners in Osaka, began making art in 2005. Like many contemporary artists and young people in Japan, he is interested in the ubiquitous kawaii (cute) subculture that is such a big, inescapable part of Japanese popular culture. He is also fascinated by fashion and possesses what his colleagues at the art workshop and its administrators all recognize as a refined sense of beauty. His favorite color is pink, and it shows up regularly in his drawings. Inspired by photographs in fashion magazines, Ueno copies and interprets the images that attract his attention as he meticulously reproduces their subjects and details — well-dressed models and their facial expressions and gestures, as well as their particular garments and accessories.

Info: Curator: Edward M. Gómez & Sarah Lombardi, La Collection de l’Art Brut, Avenue Bergières 11, Lausanne, Duration: 30/11/18-28/4/19, Days & Hours: Tue-Sun 11:00-18:00, www.artbrut.ch