ART-PRESENTATION: Monumental Minimal

Minimalism emerged in New York in the early 1960s among artists who were self-consciously renouncing recent art they thought had become stale and academic. A wave of new influences and rediscovered styles led younger artists to question conventional boundaries between various media. Their sculptures were frequently fabricated from industrial materials and emphasized anonymity over the expressive excess of Abstract Expressionism.

Minimalism emerged in New York in the early 1960s among artists who were self-consciously renouncing recent art they thought had become stale and academic. A wave of new influences and rediscovered styles led younger artists to question conventional boundaries between various media. Their sculptures were frequently fabricated from industrial materials and emphasized anonymity over the expressive excess of Abstract Expressionism.

By Dimitris Lempesis

Photo: Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac Archive

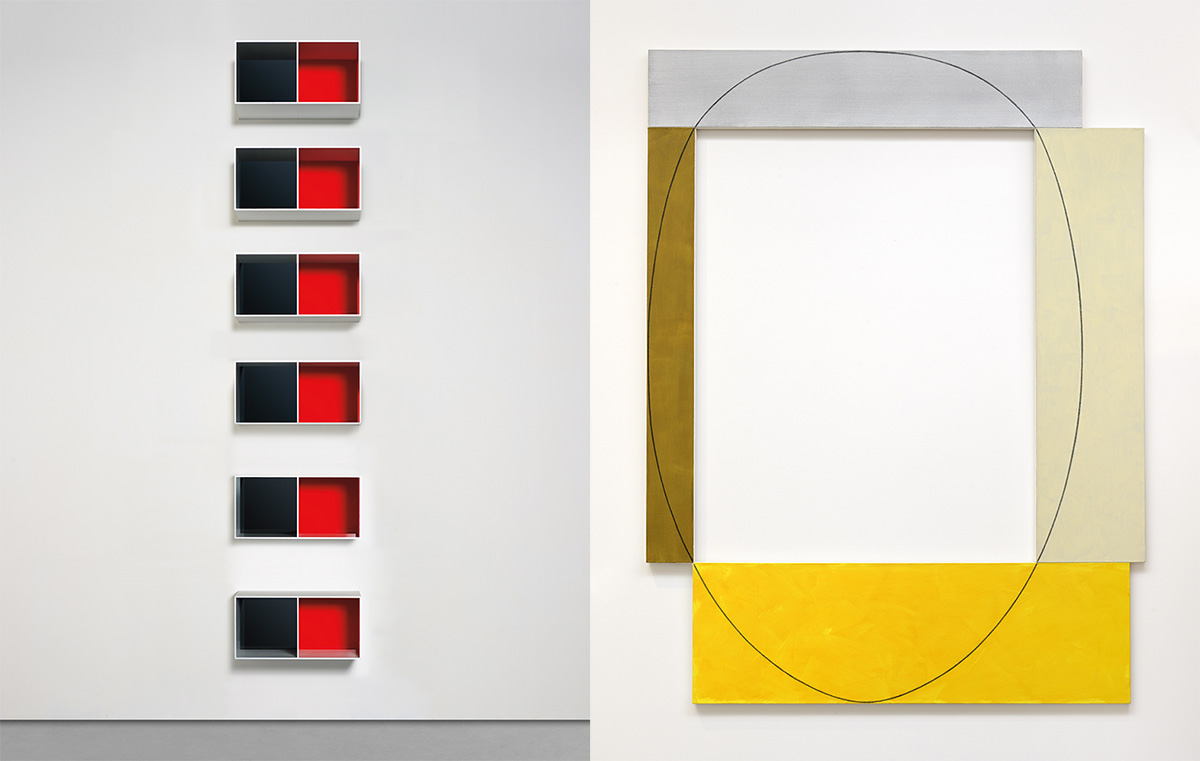

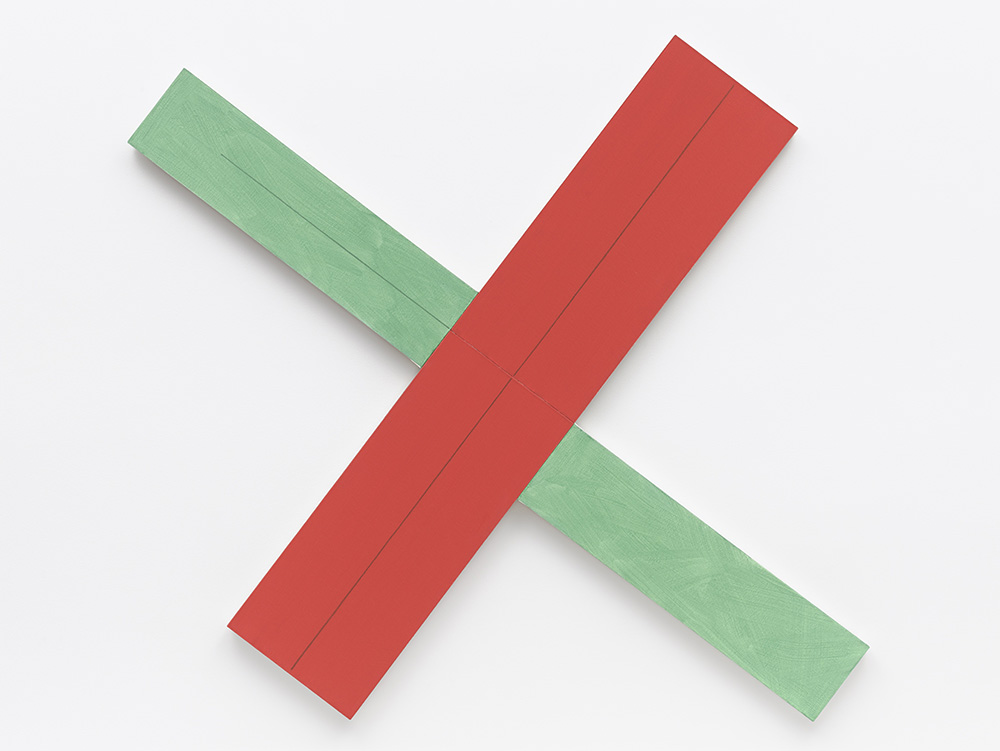

Painters and sculptors avoided overt symbolism and emotional content, but instead called attention to the materiality of the works. By the end of the 1970s, Minimalism had triumphed in America and Europe. Featuring over 20 major monumental sculptures and paintings by: Carl Andre, Dan Flavin, Donald Judd, Sol LeWitt, Robert Mangold and Robert Morris the exhibition “Monumental Minimal” at Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac is a tribute dedicated to Minimalism.One of the main characteristics of Minimal art is to re-define the viewer’s relationship with the artwork through exhibition display. The status of the work is radically changed, as demonstrated by Donald Judd’s Stacks, consisting of several identical elements mounted on a wall. The artist considers this series of work as neither paintings nor sculptures, but rather as “Specific objects”, in accordance with the term he coined in his 1965 manifesto. Donald Judd combined the use of highly finished, industrialized materials, such as iron, steel, plastic, and Plexiglas – techniques and methods associated with the Bauhaus School – to give his works an impersonal, factory aesthetic. This served to separate his works from those of the Abstract Expressionists, whose emphasis on the artist’s touch gave their images a confessional, personal context. Through its title, the exhibition seeks to explore these sculptures’ ambivalent relationship to the notion of the monument and to classical sculpture in general. Dan Flavin’s “Monument” for V.Tatlin (1967) is a distant rendition of Tatlin’s Monument to the Third International. It is one of 39 so-called monuments to the Russian Constructivist artist, Vladimir Tatlin, who Flavin held in extremely high regard. Meant to be an office building built according to the ideals of Constructivism, Tatlin’s Third International was never constructed, although the plans for the monument remain a symbol of the movement. Flavin’s Monuments have an element of impermanence that memorializes the ghost of Tatlin’s unrealized project. As Flavin stated, “The pseudo-monuments, structural designs for clear but temporary cool white fluorescent lights, were to honor the artist ironically”. This emblematic work demonstrates the importance of Constructivist theories in the development of Minimal art, and ultimately the true European rooting of an art often considered to be typically American. In the summer of 1967, Robert Morris began to purchase rectangular sheets of industrial felt and cut into them with a series of straight lines. When suspended, the strips of felt would tumble from their own weight. Morris wanted to question the fixed geometric shapes of Minimalist sculpture and the way Minimalism imposed order on materials. As he wrote in his essay “Anti-Form”, the alternative was to let materials determine their own shape. Minimal art has always been the product of transatlantic influences and exchanges. A true admirer of Constantin Brancusi, Carl Andre has recognised the influence of “La Colonne sans fin” (1918) on the modular dimensions of his own works. A similar fascination with the Romanian sculptor led Robert Morris to choose him as the subject of his Master’s thesis at Hunter College in 1966. For Robert Mangold, who was inspired by Piet Mondrian’s paintings while a security guard at MoMA, these were the only modernist works that stood the test of time, as he himself progressively deprived his painting of any external reference, focusing instead on internal formal dynamics. Josef Albers and Sol LeWitt are split by fundamentally different understandings of their work, but united by a powerful, overarching and defining goal, the avoidance of emphatic ideas of authorship. Both keep their works from getting uppity by making each one part of a serial long-term study, rather than an individual potential masterpiece. LeWitt acknowledges and pays tribute to Albers’s significance in his artistic development, and to the two men’s connections, in LeWitt’s “Wall Drawings 1176, Seven Basic Colors and All Their Combinations in a Square within a Square For Josef Albers” has been specifically recreated in its entirety for the Pantin exhibition with the help from the Estate of Sol LeWitt.

Info: Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac, 69 Avenue du Général Leclerc, Pantin, Duration: 17/10/18-23/3/19, Days & Hours: Tue-Sat 10:00-19:00, www.ropac.net