ART-PRESENTATION: Roots of The Dinner Party-History in the Making

In 1974, Judy Chicago began her most significant and most controversial work. In her drive to reinstate women’s stories into mainstream historic narrative, she was drawn to art-making techniques dismissed by the fine art world as craft, such as ceramic decoration and embroidery. Working collaboratively using the needlework and glass-based practices of artisans, Chicago created “The Dinner Party” (1974-79), that celebrated the forgotten women of Western civilization.

In 1974, Judy Chicago began her most significant and most controversial work. In her drive to reinstate women’s stories into mainstream historic narrative, she was drawn to art-making techniques dismissed by the fine art world as craft, such as ceramic decoration and embroidery. Working collaboratively using the needlework and glass-based practices of artisans, Chicago created “The Dinner Party” (1974-79), that celebrated the forgotten women of Western civilization.

By Dimitris Lempesis

Photo: Brooklyn Museum Archive

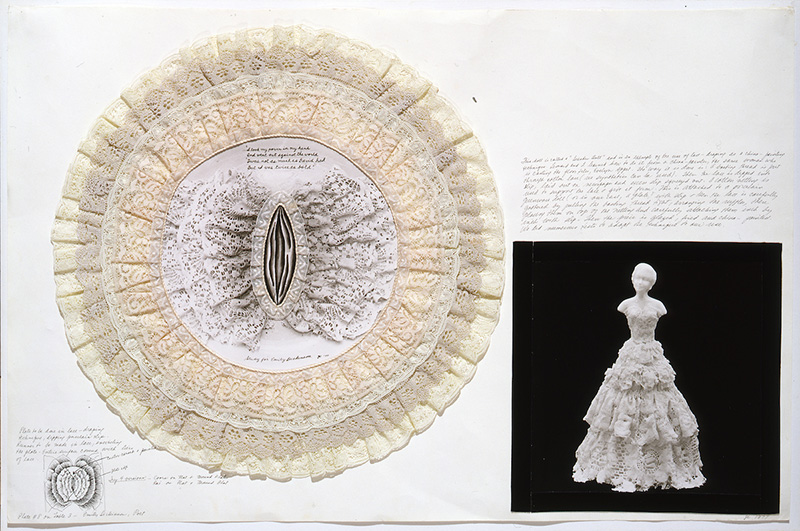

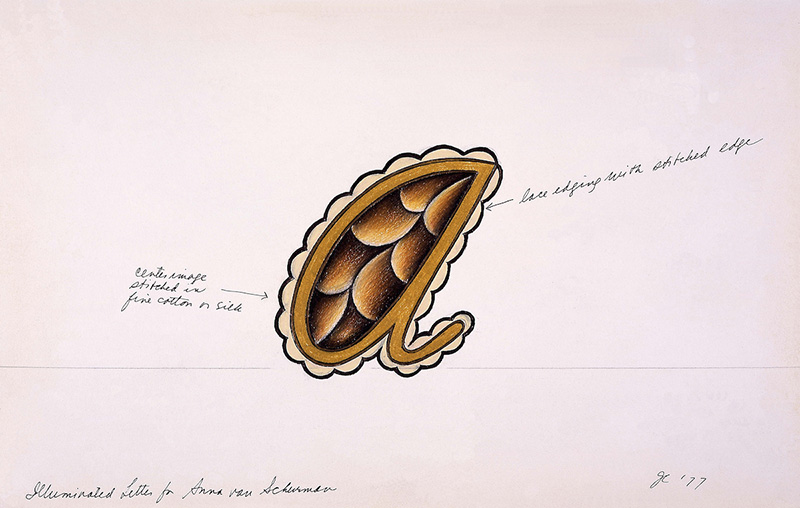

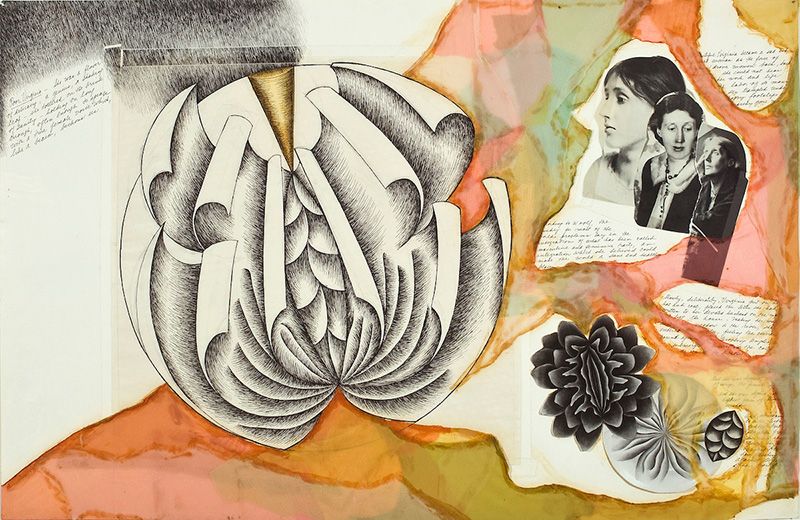

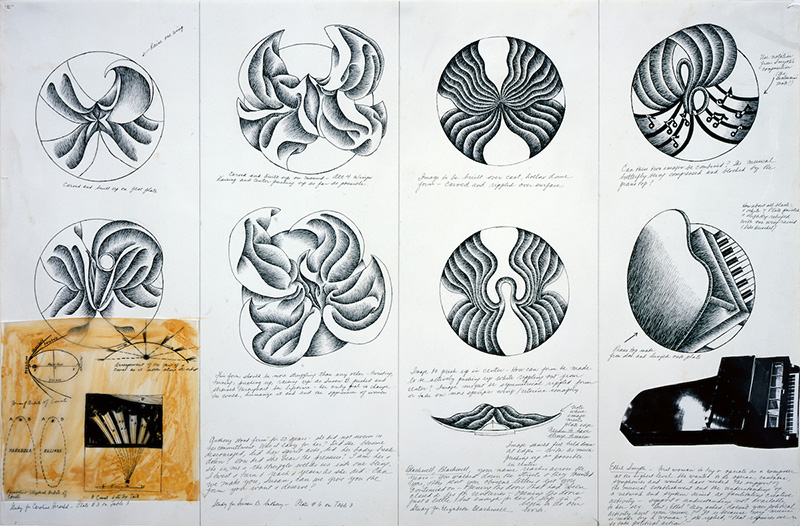

“Roots of “The Dinner Party”: History in the Making” is the first museum exhibition to examine Chicago’s evolving plans for “The Dinner Party” (1974-79), in depth, detailing its development as a multilayered artwork, a triumph of community art-making, and a testament to the power of historical revisionism. The exhibition presents rarely seen test plates, research documents, ephemera, notebooks, and preparatory drawings from 1971 through 1979 alongside “The Dinner Party”, encouraging exploration of its formal, conceptual, and material progress. The Dinner Party opened in March 1979 at the San Francisco Museum to over five thousand attendees and much discussion. Dismissed as “kitsch”, “bad art”, and “obscene” by art critics, the work was famously dismantled and stored away, rejected by institutions throughout the country. Three decades of protest and controversy surrounding the work followed until it was finally reinstalled in 2007 in a permanent exhibition space at the Elizabeth Sackler Center for Feminist Art in Brooklyn. “The Dinner Party” functions as a symbolic history of women in Western civilization/ Laid on a triangular table measuring 14.63 meter on each side. Combining the glory of sacramental tradition with the intimate detail of a carefully orchestrated social gathering, the artist represents 39 “guests of honor” by individually symbolic, larger-than-life-size china-painted porcelain plates rising from intricate textiles draped completely over the tabletops. Each plate features an image based on the butterfly, symbolic of a vaginal central core. The runners name the 39 women and contain images drawn from each one’s story, executed in the needlework of the time in which each woman lived. The dinner table stands on “The Heritage Floor”, made up of more than 2,000 white luster-glazed triangular-shaped tiles, each inscribed in gold scripts with the name of one of 999 women who have made a mark on history.The installation took six years and $250,000 to complete, not including volunteer labor. The work began modestly as “Twenty-Five Women Who Were Eaten Alive”, a way in which Chicago could use her “butterfly-vagina” imagery and interest in china painting. Chicago soon expanded it to include the thirty-nine final women arranged in three groups of thirteen. The triangular shape has significance because it has long been a symbol of the female. It is also an equilateral triangle to represent equality. The number thirteen represents the number of people who were present at the Last Supper, an important comparison for Chicago, as the only people involved there were men. Chicago developed the work on her own for the first three years before bringing in others. Over the next three years, over 400 people contributed to the creation of the work, most of them volunteers. About 125 were called “members of the project”, suggesting long-term efforts, and a small group was closely involved with the project for the final three years, including ceramicists, needle-workers, and researchers. The project was organized according to what has been called “benevolent hierarchy” and “non-hierarchical leadership”, as Chicago designed most aspects of the work and had the final control over decisions made.

Info: Curator Carmen Hermo Brooklyn Museum, 200 Eastern Parkway, Brooklyn, New York, Duration: 20/10/17-4/3/18, Days & Hours: Wed & Fri-Sun 11:00-18:00, Thu 11:00-22:00, www.brooklynmuseum.org