TRACES: Jean Tinguely

Today is the occasion to bear in mind Jean Tinguely (22/5/1925-30/8/1991). He is best known for his machinelike kinetic sculptures that destroyed themselves in the course of their operation, or Kinetic art, in the Dada tradition, known officially as metamechanics. Tinguely’s art satirized the mindless overproduction of material goods in advanced industrial society. Through documents or interviews, starting with: moments and memories, we reveal out from the past-unknown sides of big personalities, who left their indelible traces in time and history…

By Dimitris Lempesis

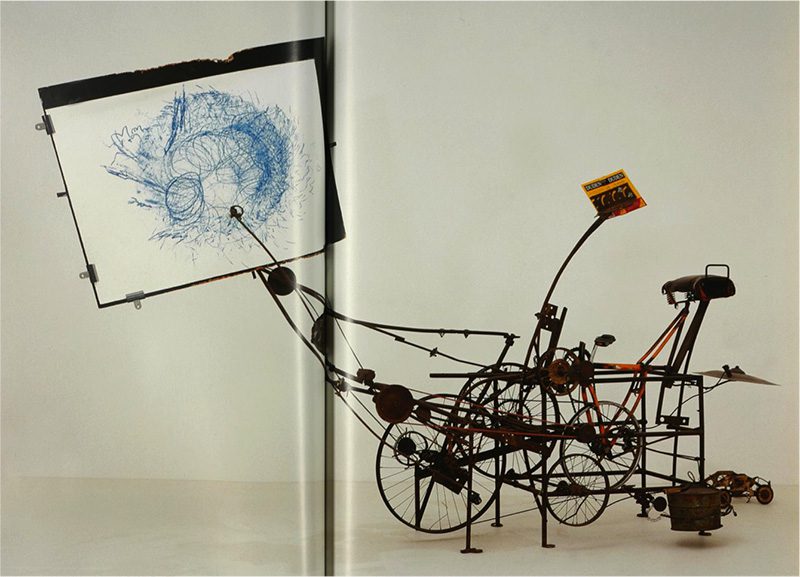

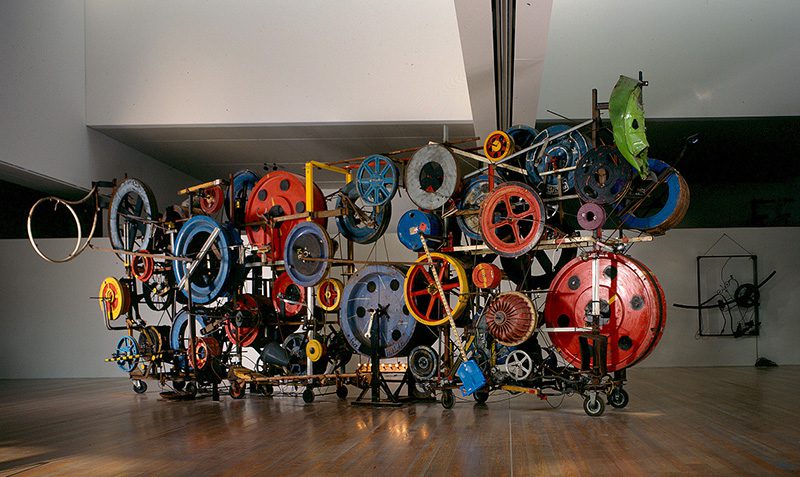

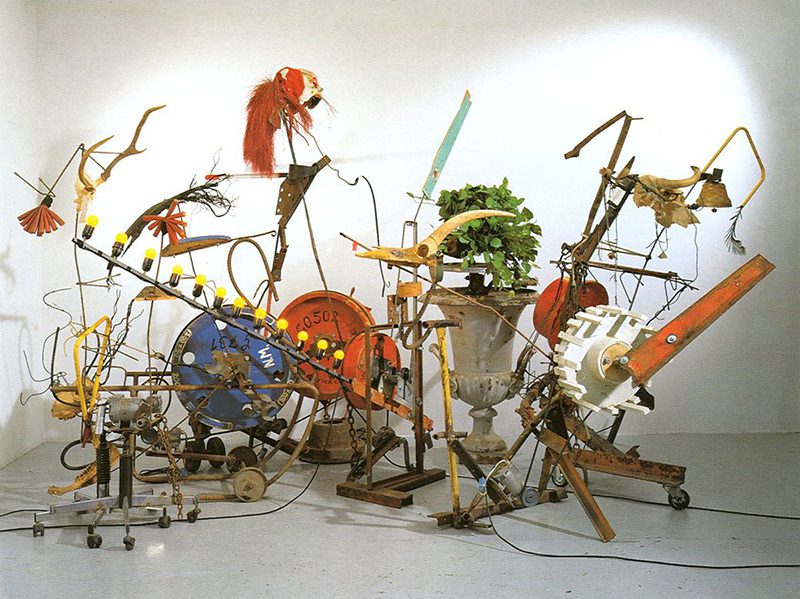

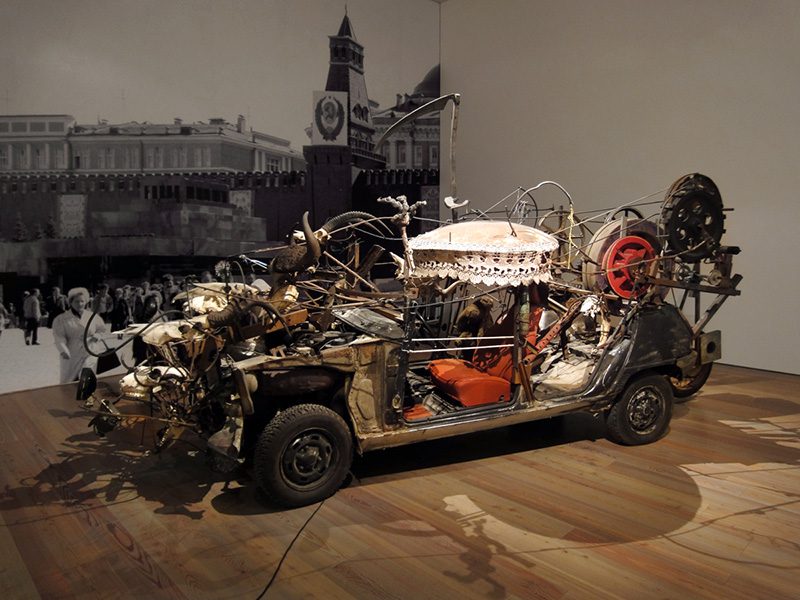

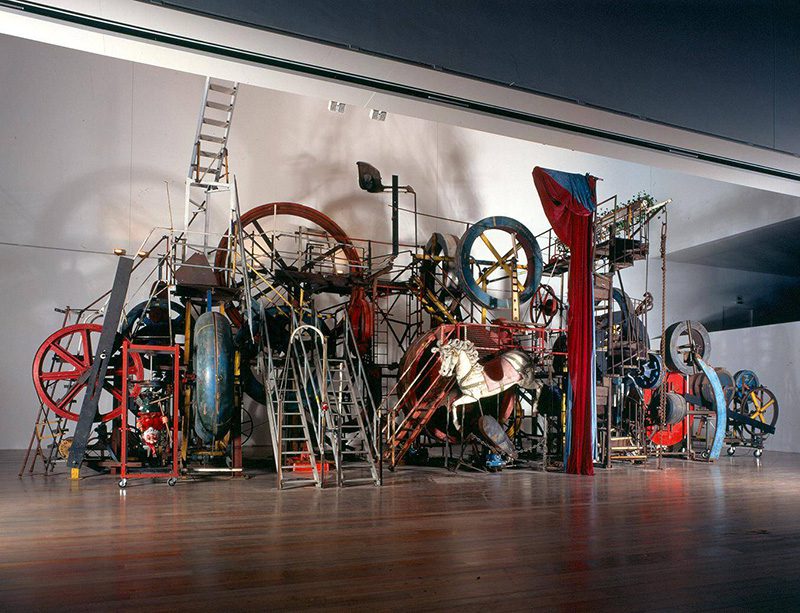

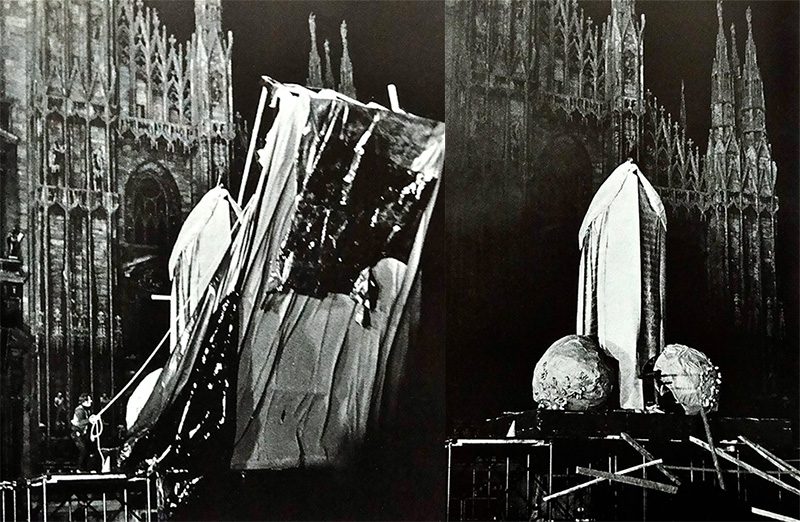

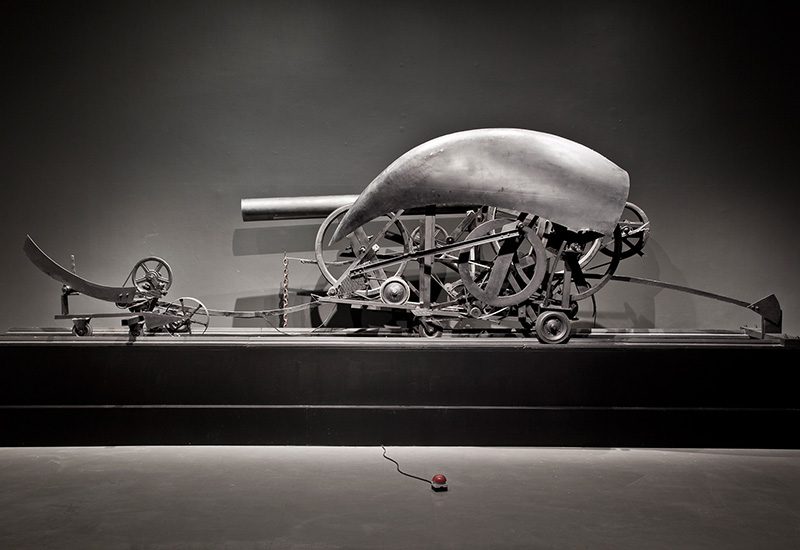

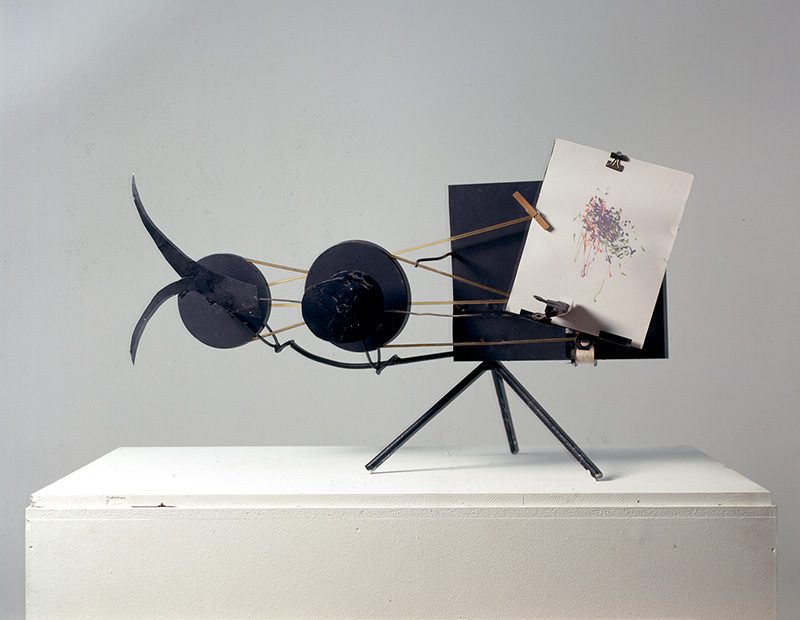

Tinguely was born in Fribourg, Switzerland. He began experimenting with mechanical sculptures in the late 1930s, hanging objects from the ceiling and using a motor to make them rotate. He attended school in Basel, but left in 1940 to undertake an apprenticeship in window decorating for a department store. In 1941, he went to study at the School of Arts and Crafts in Basel, and was exposed to a number of artistic movements that inspired his early sculptures, such as Bauhaus, Futurism and Dadaism. While all of these influences can be seen in Tinguely’s work, Dadaism is the most prominent inspiration. Growing dissatisfied with the staid artistic climate of Basel, Tinguely moved to Paris in 1953. He then began to construct his first truly sophisticated kinetic sculptures, which he termed métaméchaniques. These were robotlike contraptions constructed of wire and sheet metal, the constituent parts of which moved or spun at varying speeds. Further innovations on Tinguely’s part in the mid- and late 1950s led to a series of sculptures entitled “Machines à peindre”, these robotlike machines continuously painted pictures of abstract patterns to the accompaniment of self-produced sounds and noxious odours. The “Machines à peindre” that Tinguely set up at the first Paris Biennale in 1959 produced some 40,000 different paintings for exhibition visitors who inserted a coin in its slot. In 1960 Tinguely’s friendship with Arman, César, Raymond Hains, Yves Klein and other artists, and the art critic Pierre Restany, led to the founding of Nouveau Réalisme, which aimed at a reassessment of artistic form and material. In the mid ‘60s Tinguely produced his first monumental works for an urban setting. Welded together from scrap metal, they seem like monuments to the decline of the 19th Century cult of steam. Tinguely was meanwhile becoming obsessed with the concept of destruction as a means of achieving the “dematerialization” of his works of art. In 1960, Tinguely was asked to create a sculpture which would give a performance in front of MoMA’s Sculpture Garden. Made of wheels and pieces of scrap, Tinguely built the sculpture “Homage to New York”so that it would self-destruct. The machine ‘performed’ in front of a group of specially invited guests for 27 minutes. Once it had only partially self-destructed itself, the guests searched through remnants of the sculpture, some of them taking parts home. It has been suggested that the self-destruction of the sculpture was symbolic of New York itself, and its ability to be constantly regenerating itself. But Tinguely’s next two self-destroying machines, entitled “Study for an End of the World”, performed more successfully, detonating themselves with considerable amounts of explosives. In the ‘60s and ’70s he went on to create less aggressive and more playful kinetic constructions that combined aspects of the machine with those of found objects, or junk. In 1970, to celebrate the 10th Anniversary of the founding of Nouveau Réalisme, he built a gigantic phallus, which he exploded outside Milan Cathedral. In the ‘70s Tinguely began designing a number of fountains, but in the late ‘70s his work took a new direction. In gigantic reliefs, links with traditional image-forms appear. Tinguely’s art implicitly held a wealth of ironic social commentary. His whimsical machines deftly satirized the mindless overproduction of material goods typical of advanced industrial society. They expressed his conviction that the essence of both life and art consists of continuous change, movement, and instability, and they also served to refute the static art of the past. Tinguely was an innovator in his appreciation of the beauty inherent in machines and junk and in his use of spectator participation, in many of the events he engineered, spectators were able to partially control or determine the movements of his machines.

Tinguely was born in Fribourg, Switzerland. He began experimenting with mechanical sculptures in the late 1930s, hanging objects from the ceiling and using a motor to make them rotate. He attended school in Basel, but left in 1940 to undertake an apprenticeship in window decorating for a department store. In 1941, he went to study at the School of Arts and Crafts in Basel, and was exposed to a number of artistic movements that inspired his early sculptures, such as Bauhaus, Futurism and Dadaism. While all of these influences can be seen in Tinguely’s work, Dadaism is the most prominent inspiration. Growing dissatisfied with the staid artistic climate of Basel, Tinguely moved to Paris in 1953. He then began to construct his first truly sophisticated kinetic sculptures, which he termed métaméchaniques. These were robotlike contraptions constructed of wire and sheet metal, the constituent parts of which moved or spun at varying speeds. Further innovations on Tinguely’s part in the mid- and late 1950s led to a series of sculptures entitled “Machines à peindre”, these robotlike machines continuously painted pictures of abstract patterns to the accompaniment of self-produced sounds and noxious odours. The “Machines à peindre” that Tinguely set up at the first Paris Biennale in 1959 produced some 40,000 different paintings for exhibition visitors who inserted a coin in its slot. In 1960 Tinguely’s friendship with Arman, César, Raymond Hains, Yves Klein and other artists, and the art critic Pierre Restany, led to the founding of Nouveau Réalisme, which aimed at a reassessment of artistic form and material. In the mid ‘60s Tinguely produced his first monumental works for an urban setting. Welded together from scrap metal, they seem like monuments to the decline of the 19th Century cult of steam. Tinguely was meanwhile becoming obsessed with the concept of destruction as a means of achieving the “dematerialization” of his works of art. In 1960, Tinguely was asked to create a sculpture which would give a performance in front of MoMA’s Sculpture Garden. Made of wheels and pieces of scrap, Tinguely built the sculpture “Homage to New York”so that it would self-destruct. The machine ‘performed’ in front of a group of specially invited guests for 27 minutes. Once it had only partially self-destructed itself, the guests searched through remnants of the sculpture, some of them taking parts home. It has been suggested that the self-destruction of the sculpture was symbolic of New York itself, and its ability to be constantly regenerating itself. But Tinguely’s next two self-destroying machines, entitled “Study for an End of the World”, performed more successfully, detonating themselves with considerable amounts of explosives. In the ‘60s and ’70s he went on to create less aggressive and more playful kinetic constructions that combined aspects of the machine with those of found objects, or junk. In 1970, to celebrate the 10th Anniversary of the founding of Nouveau Réalisme, he built a gigantic phallus, which he exploded outside Milan Cathedral. In the ‘70s Tinguely began designing a number of fountains, but in the late ‘70s his work took a new direction. In gigantic reliefs, links with traditional image-forms appear. Tinguely’s art implicitly held a wealth of ironic social commentary. His whimsical machines deftly satirized the mindless overproduction of material goods typical of advanced industrial society. They expressed his conviction that the essence of both life and art consists of continuous change, movement, and instability, and they also served to refute the static art of the past. Tinguely was an innovator in his appreciation of the beauty inherent in machines and junk and in his use of spectator participation, in many of the events he engineered, spectators were able to partially control or determine the movements of his machines.