PRESENTATION: Radio Luxembourg-Echoes across borders

The exhibition “Radio Luxembourg: Echoes across borders” retraces the plurality of artistic practices from the 1990s until today, with the exception of one work from the 1960s. Throughout the exhibition, artists explore spatial relationships and propose new approaches, particularly through the lens of language. Architecture and everyday objects serve as fertile sources of inspiration, while materials and fabrication processes – whether artisanal or industrial – reflect the evolving history of forms and techniques shaped by globalized capitalism. Artworks from the personal collection of Gaby and Wilhelm Schürmann punctuate the presentation, introducing shifts in scale and diverse approaches to portraiture.

By Dimitris Lempesis

Photo: Mudam Archive

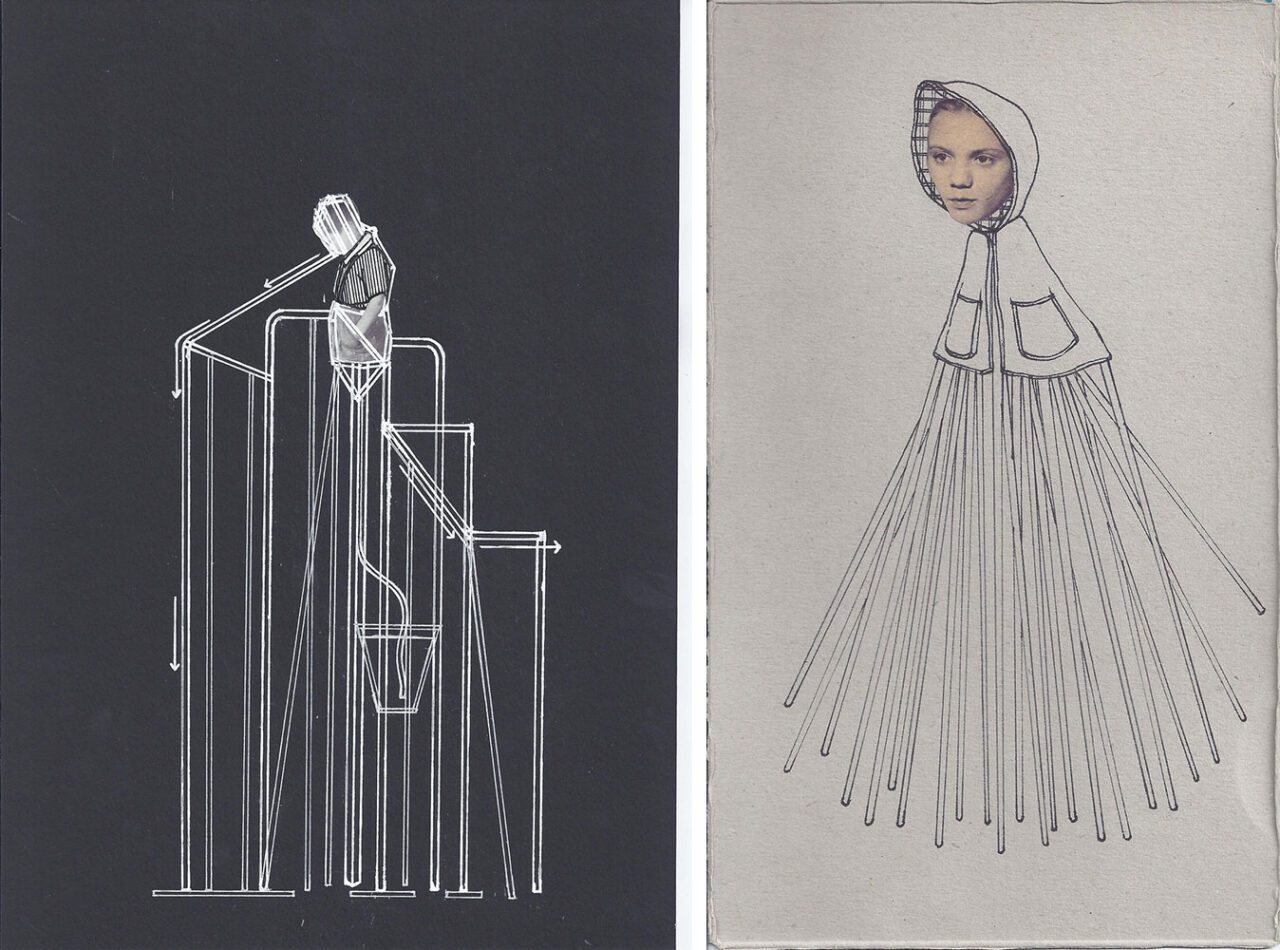

The works presented in Mudam’s new display entitled “Radio Luxembourg: Echoes across borders”, can be understood in relation to the heritage of conceptual art of the 1970s and 1980s. While the 1980s are often remembered for their return to figuration, the decade also gave rise to a broad spectrum of ideas and experimental forms. It was a moment marked by critical analyses of mass media, consumerism and capitalist structures, alongside the emergence of digital technologies and urban art practices. The exhibiting artist’s research engages with the upheavals of their time, intertwining with the cultural, political and social history of the past thirty years. Their work reflects societal transformations, highlighting aspirations, uprisings and forms of resistance at the turn of the 21st century. It questions the validity of dominant models, exposes the flaws of political regimes and imagines alternatives. Notable works include “Defense of Necessity” (2003) by Andrea Bowers and “Stairway” (2010) by Monika Sosnowska, both of which stand as significant mile- stones in the artists’ careers. Additional highlights include works by Carine Krecké, Annette Kelm, Zoe Leonard, Hendl Helen Mirra, Henrike Naumann and Diana Thater, among others. The practices of these women artists resonate with the political and cultural transformations of the past three decades—their work reflecting periods of significant social change, collective struggles and movements of resistance, challenging dominant narratives while imagining alternative futures. Andrea Bowers’ practice is inextricably linked to her activism. Her works often begin in the extensive archive she has assembled around American society, shaped by her relationships to various activist communities. Her terrain spans gun laws, civil rights, labor movements, immigrant rights, global warming and ecofeminism, subjects she approaches through the lens of civil dis- obedience and pacifism. “Defense of Necessity” (2003) refers to the ‘Women’s Pentagon Action’ of 1980, which brought 2,000 women to Washington, D.C., as well as the ‘Greenham Common Women’s Peace Encampment’ that began in 1981 near the eponymous Royal Air Force base in southern England. Weaving, adopted as a tool of protest during anti-nuclear demonstrations, became a symbol and strategy. In Bowers’ work, textile and embroidery recall this gesture, serving as metaphors for resilience of women confronting state power. The artwork functions as a barrier within the exhibition space, accompanied by a book and two photorealistic drawings based on historical images. The title references the legal notion ‘necessity defence’, a justification for illegal acts committed to avoid greater harm. It encapsulates Bowers’ belief in the moral imperative of resistance and underscores the paradoxes inherent to civil resistance – where the line between peaceful protest and unlawful action becomes porous. In 1989, Jessica Diamond painted the words ‘I HATE BUSINESS’ on a brick wall in New York. The message is blunt, its critique uncompromising. In just three words, she unequivocally denounced capitalism, and the difficulties artists faced due to an art market that had exploded in 1980s New York. Diamond emerged during this period but resisted its commercial imperatives by turning to site-specific mural painting, drawing on the immediacy and subversive spirit of urban graffiti. Diamond credits the radical urgency of the work to language itself, which she displaces into the controlled environment of the gallery. When presented in a museum or commercial gallery, I Hate Business openly questions the very economic systems that sustain such institutions. Words, the artist’s primary artistic material, erupt across the walls, rendered by hand directly on their surface. They become both pictorial and tactile, set against a carefully painted background that mimics expressive brushstrokes. This creates a productive tension: between the directness of the message and the deliberate care of its execution. The scale of the lettering, adapted to each presentation, underscores this friction, responding to the architecture of the space. An additional focal point is “Nude Wing” (2011), a monumental work by British artist Fiona Banner aka The Vanity Press, installed in the museum’s Grand Hall. Engaging in dialogue with Mudam’s iconic architecture by I. M. Pei, Banner transforms military aircraft components into sculptural forms that interrogate the tension between technological beauty and destructive power. Polished to a mirror-like finish, the six-meter-high wing reflects its surroundings, integrating visitors into the work. Through this installation, Banner prompts reflection on the aestheticization of weaponry, collective memory and the narratives that shape our perception of history. Eva Kot’átková’s work reveals the social norms that govern both individual and collective behaviour. In “Controlled Memory Loss” (2009-10), she interrogates the notion of home and domestic space, likening it to a constraining social framework. Of Czech origin, Kot’átková was born in a country shaped by Soviet influence, where collective rules predominated. By exposing their impact on the individual, she seeks to open alternatives that foster emancipation. The human plays a central place in the installation. Her maquettes evoke spaces of normative life and the architectural standardization of housing projects. This sense is reinforced by the repetition of black geometric modules assembled like a sculpture. Her drawings and collages are reminiscent of Surrealism, a movement that was particularly active in former Czechoslovakia in the 1930s. These works expose the often-invisible forms of control that persist in our societies today, continuing to subjugate bodies.

Nora Turato’s “i am happy to own my implicit biases” (malo mrkva, malo batina) (2018-20) is a sonic installation composed of a big black metal structure, originally created for the San Lorenzo Oratory in Palermo as part of Manifesta 12. Evocative of a cage, a locker room, or a confessional, the grated framework functions simultaneously as a stage, a setting for the artist’s performances and a bench where visitors can sit and engage in conversation. The work is accompanied by a recording of Nora Turato’s voice, captured during her performance in Palermo and broadcast through speakers positioned at the top of the structure. At the heart of the story are the doñas de fuera – ladies from the Outside – female spirits from Sicilian folklore whose name dates to the Spanish occupation of the island. These mythical figures were said to haunt women accused of witchcraft during the Inquisition. Turato invokes them as part of a broader reflection on the silencing of women in patriarchal societies giving voice and presence to the marginalized through her commanding vocal performance. The soundtrack is composed of fragmented English-language dialogues drawn from a wide range of sources – folklore, literature, internet forums, stereotypes and everyday banalities. Through her signature cut-and-paste style, Turato reconfigures these fragments into a dissonant yet incisive monologue that questions gender norms, challenges dominant narratives and disrupts cultural canons “Untitled” (2001) by Zoe Leonard comprises five ordinary suitcases placed side by side. The repetition of different sizes and colors lends the work a strong physical presence. Collected by the artist from friends and acquaintances, the suitcases bear the patina of time. Scratches, tears and luggage tags that testify to their past usage and infuse them with an affective, personal value. For Leonard, these suitcases also function as portraits. She later developed a related, evolving work titled 1961 – the year of her birth – comprising as many suitcases her age. These objects carry memories and evoke a sense of a shared experience. Leonard extracts existing objects from the world and presents them in a new light. Her sculptural works are influenced by her photographic practice, a medium she has engaged with since the 1980s and which she considers a physical act of looking. Henrike Naumann explores how interior design and everyday objects reflect historical conditions and socio-economic change. In the aesthetics of domestic life, she discerns the ideological tensions and questions of identity that shape contemporary German society. “Aufbau West” (2017) was created for an exhibition of the same name in Cologne, in which Naumann transformed an abandoned storefront by reconstructing it as a second-hand shop. Using furniture and household trinkets – materials rich in cultural memory – she infuses the space with layers of sociopolitical meaning. One piece from this project features an improbable mirrored shelf in the shape of a cloud, holding a selection of vintage items. These objects are characteristic of the former Federal Republic of Germany, though some, such as the pack of ‘West’ cigarettes, were also popular in the former East. The title subverts the slogan Aufbau Ost, a phrase used after German reunification in 1990 to describe the state-led ‘reconstruction’ of the Eastern federal states, a process often viewed as paternalistic and marked by widespread disillusionment. Born in former East Germany, Naumann experienced this period firsthand, including the rise of political extremism that accompanied it. “Aufbau West” becomes a portrait of an ostensibly prosperous Western consumer culture, one that, in her view, offers only a diluted version of itself. Monika Sosnowska’s practice investigates the relationship between structure and space, often playing with the tension of monumental scale. Drawing from existing architectural forms, she reveals the material remnants of urban transformation. “Stairway” (2010) takes inspiration from an emergency staircase once attached to the rear of a building in Tel Aviv – discovered by the artist just before its demolition and recreated here, at human scale, in steel. The fire escape, first introduced in the 19th century, has since evolved into various iterations but remains emblematic of a utilitarian, modernist approach shaped by industrial engineering. In the collective imagination, it represents a functionalists strand of architectural modernity. In Poland, where Sosnowska was born during the communist era, such staircases are commonly found on residential buildings from the 1950s. In this sculpture, however, the staircase is distorted: compressed between floor and ceiling, it has been stripped of all practical use. Its twisted, collapsed form suggests the aftermath of a catastrophe. Sosnowska is deeply interested in how architecture, through its styles, materials and construction modes, encodes the political and ideological values of societies. Diana Thater’s work draws on disciplines such as literature, sociology and behavioural science to explore the interactions between human beings, animals and nature. “The Individual as a Species” (1996) resonates with Electric Mind, a script published by the artist the same year and inspired by Rachel in Love (1987), a science fiction novel by American writer Pat Murphy (1955). In the story, a scientist transfers the consciousness – or “electric mind” – of his deceased daughter into the brain of a chimpanzee. Three of the five monitors in Thater’s installation display show footage of a monkey undergoing daily training at an animal center. The monitors are placed directly on the ground, lending the images a materiality in the space. By multiplying points of view and disrupting linear editing, Thater encourages the viewer to make new associations and resist narrative progression. She inserts color fields and isolated syllables into the visual flow–elements that appear meaningless at first glance but function as part of a deliberate narrative deconstruction. These interventions help to construct a new filmic grammar through which the artist challenges binary oppositions such as wild/domestic or nature/technology.

Participating Artists: Leonor Antunes, Fiona Banner aka the Vanity Press, Andrea Bowers, Miriam Cahn, Jessica Diamond, Dominique Ghesquière, Annette Kelm, Eva Kot’átková, Carine Krecké, Zoe Leonard, Isa Melsheimer, Hana Miletić, Hendl Helen Mirra, Henrike Naumann, Charlotte Posenenske, Monika Sosnowska, Joëlle Tuerlinckx, Diana Thater, Nora Turato

Photo: Diana Thater, The Individual as a Species, 1996 (video still), Collection Mudam Luxembourg – Musée d’Art Moderne Grand-Duc Jean, Donation 2023 – Gaby and Wilhelm Schürmann with the support of the members of the Cercle des collectionneurs du Mudam Luxembourg, Courtesy of the artist

Info: Curators: Wilhelm Schürmann and Marie-Noëlle Farcy, Assistant Curator: Vanessa Lecomte, Mudam Luxembourg (Musée d’Art Moderne Grand-Duc Jean), 3 Park Dräi Eechelen, Luxembourg-Kirchberg, Luxemburg, Duration: 4/4/25 – 11/1/26, Days & Hours: Tue & Thu-Sun 10:00-18:00, Wed 10:00-21:00, www.mudam.com/

Right: Eva Kot’átková, Untitled, 2010, From the series Controlled Memory Loss, 2009 – 10, Set of 24 drawings and collages, Collection Mudam Luxembourg – Musée d’Art Moderne Grand-Duc Jean, Acquisition 2011, © Eva Kot’átková

Right: Monika Sosnowska, Stairway, 2010, Collection Mudam Luxembourg – Musée d’Art Moderne Grand-Duc Jean, Donation 2023 – Gaby and Wilhelm Schürmann with the support of the members of the Cercle des collectionneurs du Mudam Luxembourg View of the exhibition Monika Sosnowska, 15/3-17/4/2014, Capitain Petzel, Berlin, Photo: Wilhelm Schürmann, Herzogenrath