PRESENTATION: Imagining Black Diasporas-21st-Century Art and Poetics

“Diaspora” is a word typically associated with displacement. People move and are forcibly moved, and their cultures disperse. But diasporas also provoke creative acts of survival, as people reinvent their heritage through art. Artists featured in the exhibition interpret their heritage through the clues and motifs their predecessors left behind. Some reflect on the impact of the slave trade, while others respond to migrants’ experiences in this century.

“Diaspora” is a word typically associated with displacement. People move and are forcibly moved, and their cultures disperse. But diasporas also provoke creative acts of survival, as people reinvent their heritage through art. Artists featured in the exhibition interpret their heritage through the clues and motifs their predecessors left behind. Some reflect on the impact of the slave trade, while others respond to migrants’ experiences in this century.

By Dimitris Lempesis

Photo: LAMCA Archive

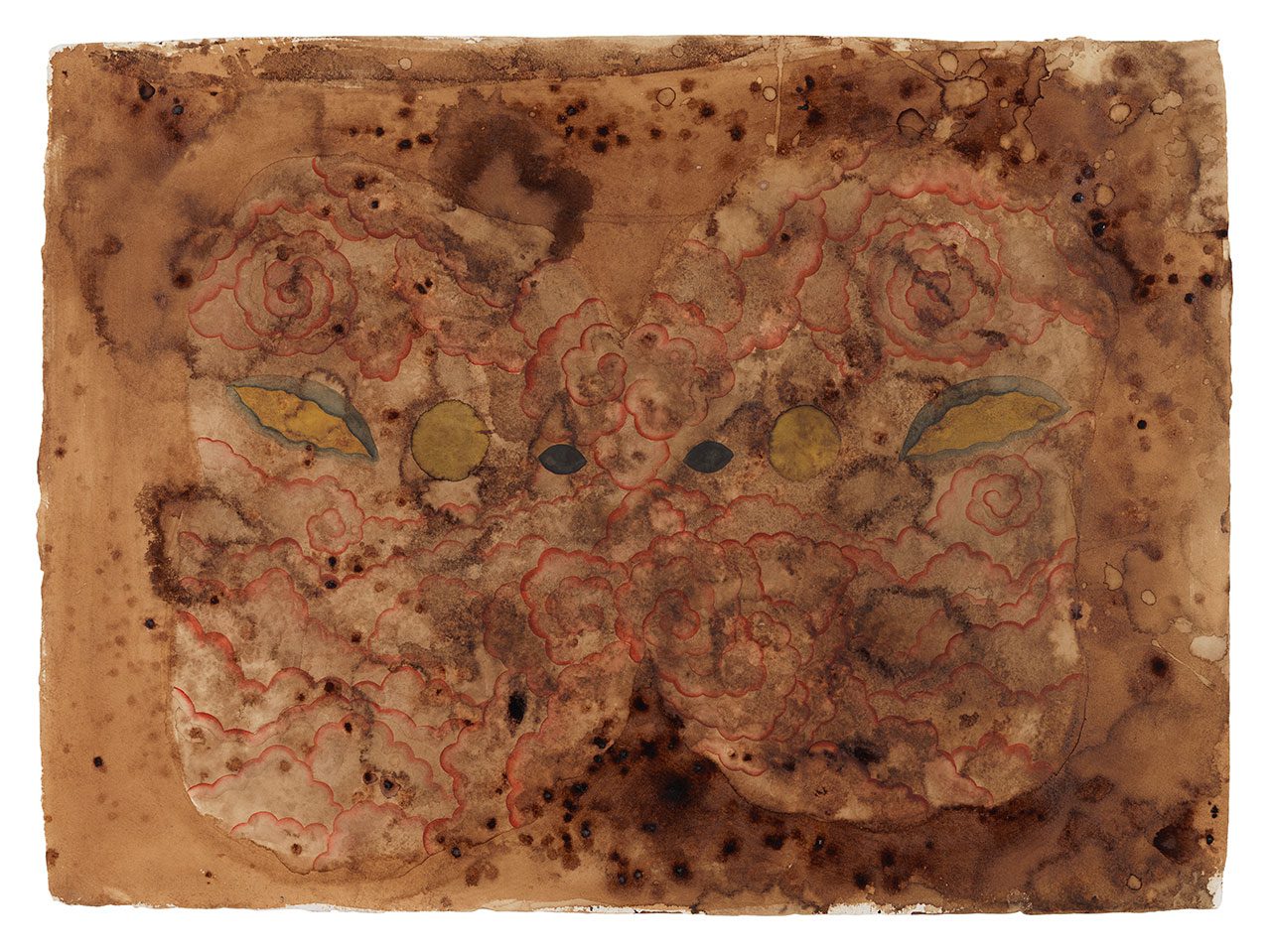

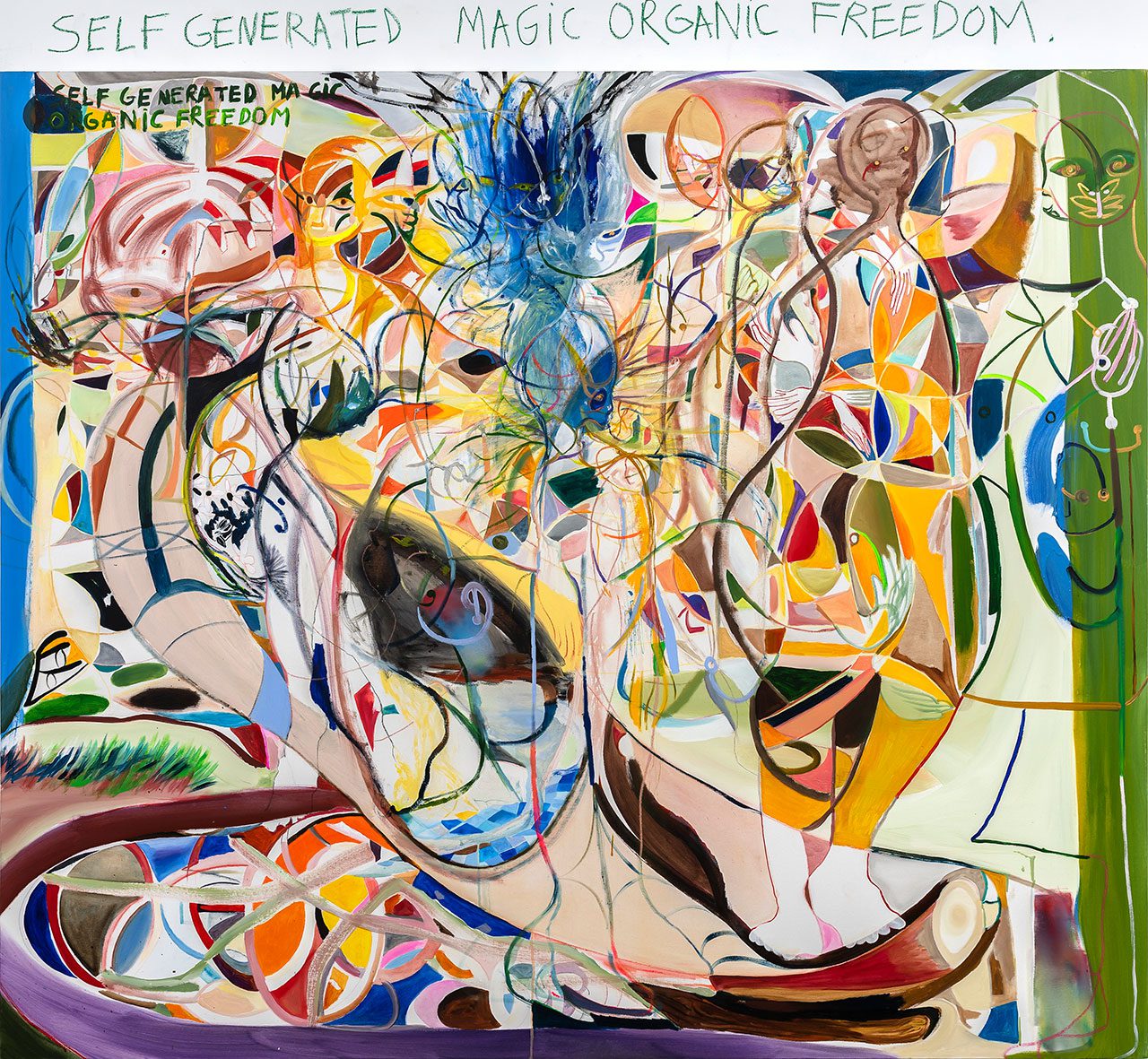

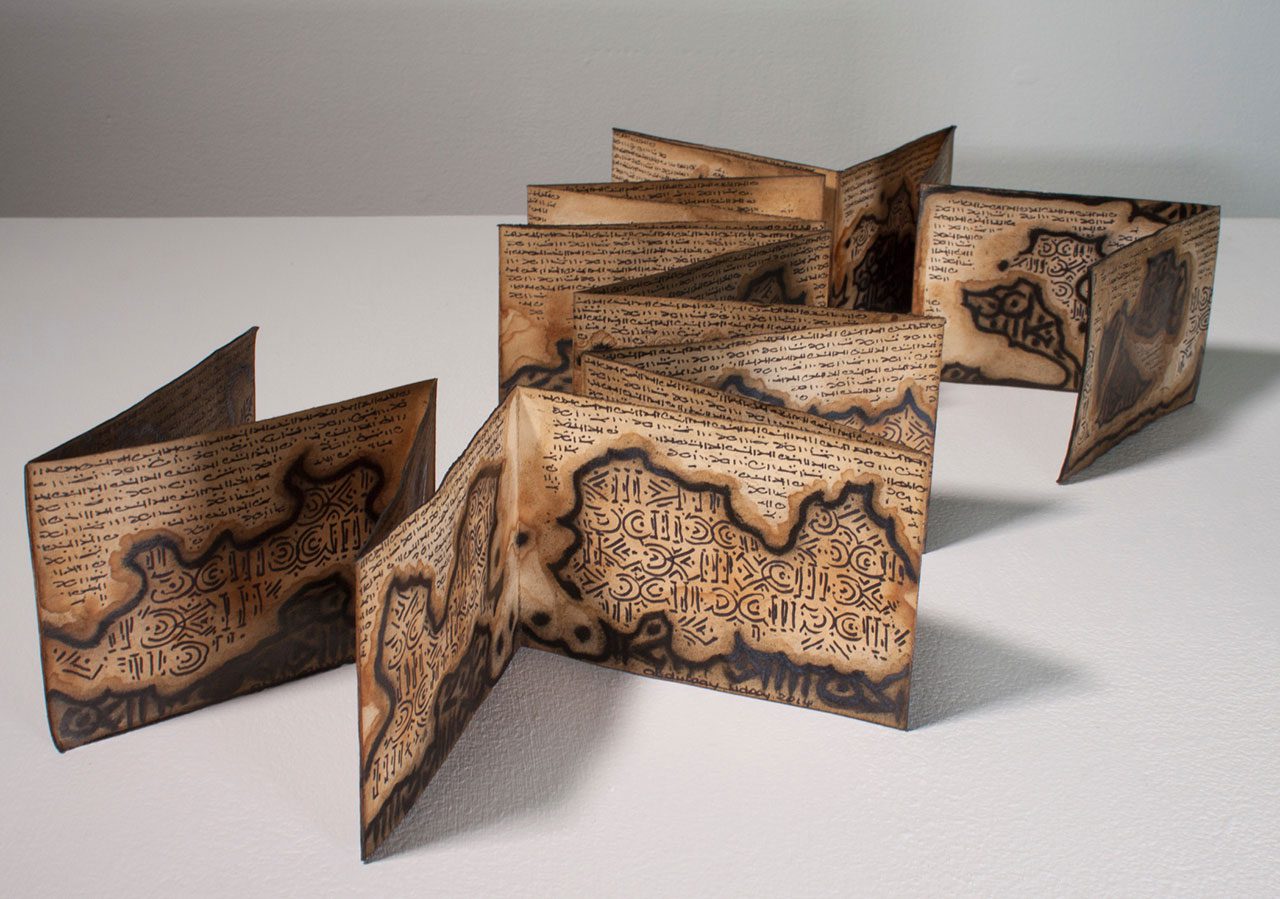

The exhibition “Imagining Black Diasporas: 21st-Century Art and Poetics” expands the Pan-African exhibition canon, which has historically focused on the Black Atlantic by showcasing artists working adjacent to the Pacific. Seventy artworks (painting, sculpture, photography, works on paper, and time-based media) are organized into four themes: speech and silence, movement and transformation, imagination, and representation. The first section, “Speech and Silence”, explores the power and limitations of language. Speaking out or staying quiet can have fatal consequences. Artists across regions use the written word as a visual motif and explore the aesthetic language of quiet and erasure. In tandem, silence is also examined as a creative state, anticipating speech like a pause before a beat. In “Movement and Transformation” artists depict the human body in motion, examining histories of migration and the transformational power of movement. In this section artists move their bodies to enact or resist confinement, from a work depicting a dancer’s body flowing in a copper mine in Lubumbashi, Democratic Republic of the Congo, to dancing in the Watts neighborhood of Los Angeles. Diaspora is vast and crowded. The artists featured in “Imagination: use abstraction and collage to examine a cacophony of experiences. Here, fragmentation is a key aesthetic strategy that interrogates the authority of images and the erasures embedded within them. Abstracted landscapes frame diaspora as psychological terrain, while reinterpretations of imagery from museum catalogues, history books, print media, and the internet create complex layers of meaning. Dehumanizing pictures of Black people justified European conquest throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Despite such portrayals, in 1839, American abolitionist Frederick Douglass identified the power of photography to transform how people saw one another and themselves. The exhibition’s final section, “Representation”, presents a series of portraits and self-portraits by photographers who critically engage with the history of the medium, from its role in imperialism to the politics of looking and being seen. The artists create depictions related to longing and disappearance, putting themselves at the centers of their personal or ancestral migration stories. Among the highlights of the exhibition are: Igshaan Adams grew up in Bonteheuwel, a predominantly working-class township in southeast Cape Town. The designs of his beaded textiles like “Aunty Lovey se Kombuis” (2022) are inspired by the geometric patterns found in linoleum floors common in homes throughout the township. With glass beads, shells, and wires, Adams highlights the material aspects of domestic spaces along with the memories held within them. The works’ geometry also resembles the patterns that form in the soil when people cross racially segregated borders that separate the townships. The portraits in Sandra Brewster’s “Blur “series (2017–20) have the materiality of a wallet-sized photographic keepsakes with the presence of towering sculptures— spanning 20 feet high. Brewster’s parents were part of a large Guyanese migration to Canada and the United States during the 1960s and ’70s after Guyana gained its independence from Dutch and British control in 1966. The Brewster family arrived in Toronto from Guyana in the 1960s, settling in the immigrant-dense suburb of Pickering when the artist was nine. Throughout her life, Brewster has observed the challenges immigrants in her community face. Widline Cadet works in Los Angeles as an artist and professor at the University of California, Los Angeles. She is known for a distinct visual language that explores visibility, Black femininity, and interiority. In the self-portrait “Seremoni Disparisyon #1” (Ritual [Dis]Appearance #1) (2019), she uses photography to examine her experience as a Black woman who migrated to the United States from Haiti and the acts of survival her relocation entailed. In “KAMARIA KPATASCO GRC” (2019), Ibrahim Mahama depicts the tattooed forearm of a migrant and friend of the artist, on top of leather he salvaged from passenger seats from the Gold Coast Railway in Ghana. The British government ordered the construction of the Gold Coast Railway in the 1890s to transport military machinery, mined resources, and produce. The leather background in “KAMARIA KPATASCO GRC” loosely resembles the shape of the continents of Europe and Africa, suggesting interactions between the Global North and the Global South, as well as those between cities in Ghana. Frida Orupabo searches platforms like Google, Instagram, and Pinterest, collaging digital images into otherworldly compositions. Orupabo’s collages such as “Untiled” (2018) and “Untitled (Sources unknown except Shadman Shahid [bottom left])” (2019) are fantastic and often grotesque. Arms and legs bend in irregular directions; subjects defy the logic of space and scale. Orupabo’s practice evokes the nonsensical way the mind constructs images in dreams and intervenes in the way Black people have been historically seen and portrayed. Adam Pendleton has said he became fascinated with language when the so-called stand-your-ground laws in force in thirty-eight of the 50 U.S. states gained widespread attention amid Black Lives Matter protests. Pendleton said he wanted to create a language that could stand its ground. Pendleton’s “Our Ideas #4” (2018–19) comprises 32 prints the artist assembled into a grid. Repurposing images of tribal masks from African Chokwe, Punu, and Dogon tribes, ceremonial artifacts, and photographs of Black people, he overlaid these with shapes and phrases that symbolically threaten to overflow their frames. Pendleton creates a space where the urban collides with the rural, the refined with the barbaric, and the white with the black. In “Dibujo Intercontinental” (2017), Cuban artist Susana Pilar Delahante Matienzo wrapped a rope around her waist and tied it to a wooden boat, attempting to drag it across a piazza in Venice, Italy during the 2017 biennale. The rope is the line—the drawing—that connects Delahante Matienzo to her Chinese and African ancestors. Lorna Simpson began composing icy landscapes on panels with photographic imagery, paint, and ink in 2016. Drawn to the linguistic connections of ice to isolation and to the solemn majesty of night landscapes, Simpson has developed a meditative, at times disquieting, series of landscapes. For “Detached Night” (2019), she layered silkscreened images of glaciers and smoke, dripping indigo acrylic onto fiberglass and canvas into an engrossing vision of an icy world most humans have only seen in photographs. She added fragments of editorial text and advertisements. While the photographs in the painting portray a recognizable landscape, their imperfect registrations mirror the fragmented activity of the subconscious.

Photo: Kambui Olujimi, In Your Absence The Skies Are All The Same, 2014, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, purchased with funds from the Ralph M. Parsons Fund, © Kambui Olujimi, digital image © Museum Associates_LACMA

Info: Curator: Dhyandra Lawson, Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA), 5905 Wilshire Boulevard, Los Angeles, CA, USA, Duration: 15/12/2024-3/8/2025, Days & Hours: Mon-Tue & Thu 11:00-18:00, Fri 11:00-20:00, Sat-Sun 10:00-19:00, www.lacma.org/

Right: Ibrahim Mahama, KAMARIA KPATASCO GRC, 2019, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, purchased with funds provided by the Ralph M. Parsons Fund, © Ibrahim Mahama, photo © Museum Associates_LACMA

![Left: Lorna Simpson, Detached Night, 2019, © Lorna SimsponRight: Widline Cadet, Seremoni Disparisyon #1 (Ritual [Dis]Appearance #1), 2019, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, gift of Avo Samuelian and Hector Manuel Gonzalez, © Widline Cadet, photo © Museum Associates_LACMA](http://www.dreamideamachine.com/web/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/05-5-scaled.jpg)

Right: Widline Cadet, Seremoni Disparisyon #1 (Ritual [Dis]Appearance #1), 2019, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, gift of Avo Samuelian and Hector Manuel Gonzalez, © Widline Cadet, photo © Museum Associates_LACMA