TRIBUTE: Pop Forever, Tom Wesselmann &…

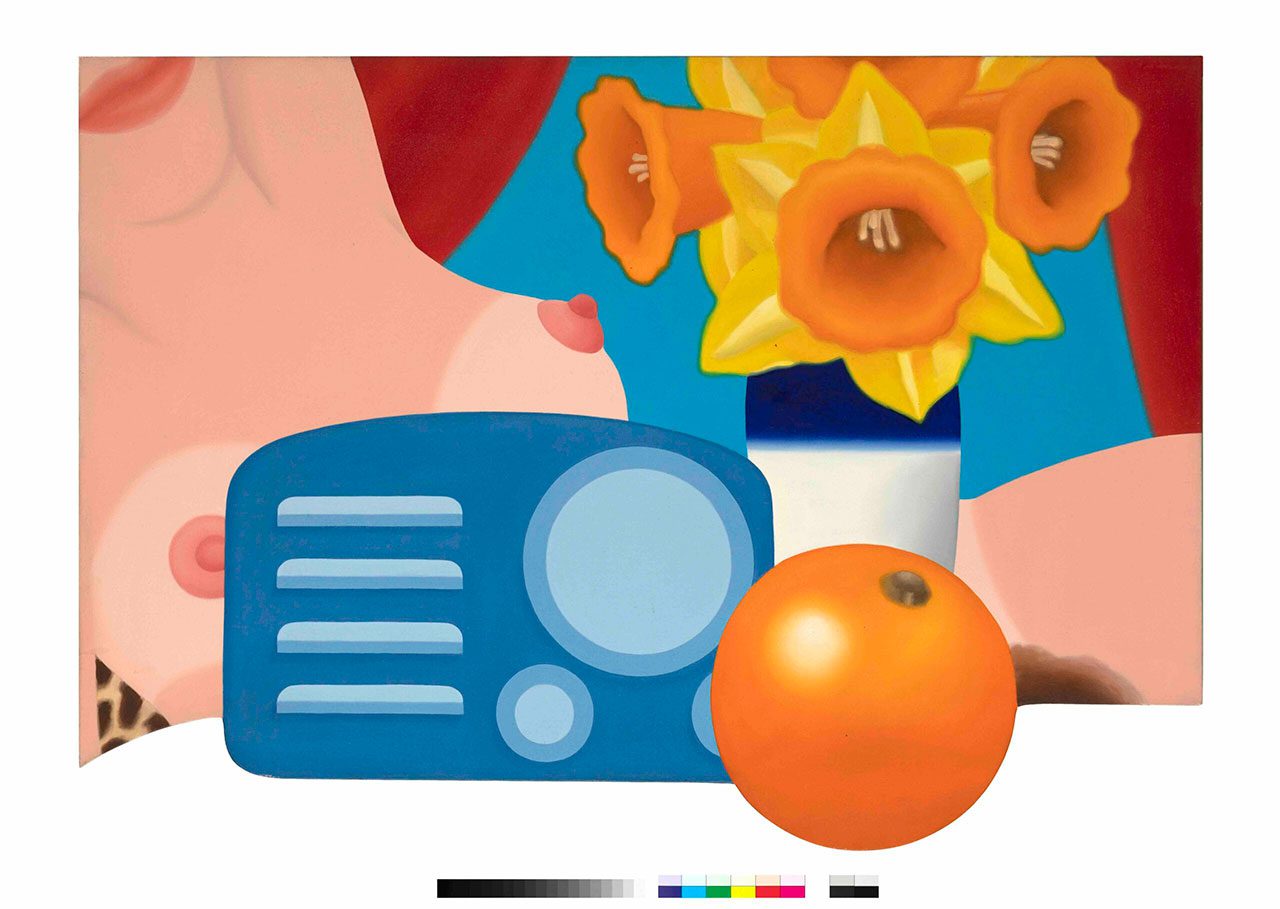

Tom Wesselmann emerged as a pivotal figure in the American Pop Art movement of the 1960s, setting aside abstract expressionism to embrace classical representations. His nudes, still lifes, and landscapes, carved out a unique niche with its integration of collage elements and assemblages. These works often included everyday objects and advertising materials, reflecting his ambition to create imagery as impactful as the abstract expressionism he revered. Wesselmann is renowned for his ‘American Nude’ series, marked by sensuous forms and vibrant colors. His ‘Standing Still Life’ series of the 1970s, featuring free-standing shaped canvases, magnified intimate objects to an impressive scale, showcasing his innovative approach to art.

Tom Wesselmann emerged as a pivotal figure in the American Pop Art movement of the 1960s, setting aside abstract expressionism to embrace classical representations. His nudes, still lifes, and landscapes, carved out a unique niche with its integration of collage elements and assemblages. These works often included everyday objects and advertising materials, reflecting his ambition to create imagery as impactful as the abstract expressionism he revered. Wesselmann is renowned for his ‘American Nude’ series, marked by sensuous forms and vibrant colors. His ‘Standing Still Life’ series of the 1970s, featuring free-standing shaped canvases, magnified intimate objects to an impressive scale, showcasing his innovative approach to art.

By Dimitris Lempesis

Photo: Fondation Louis Vuitton Archive

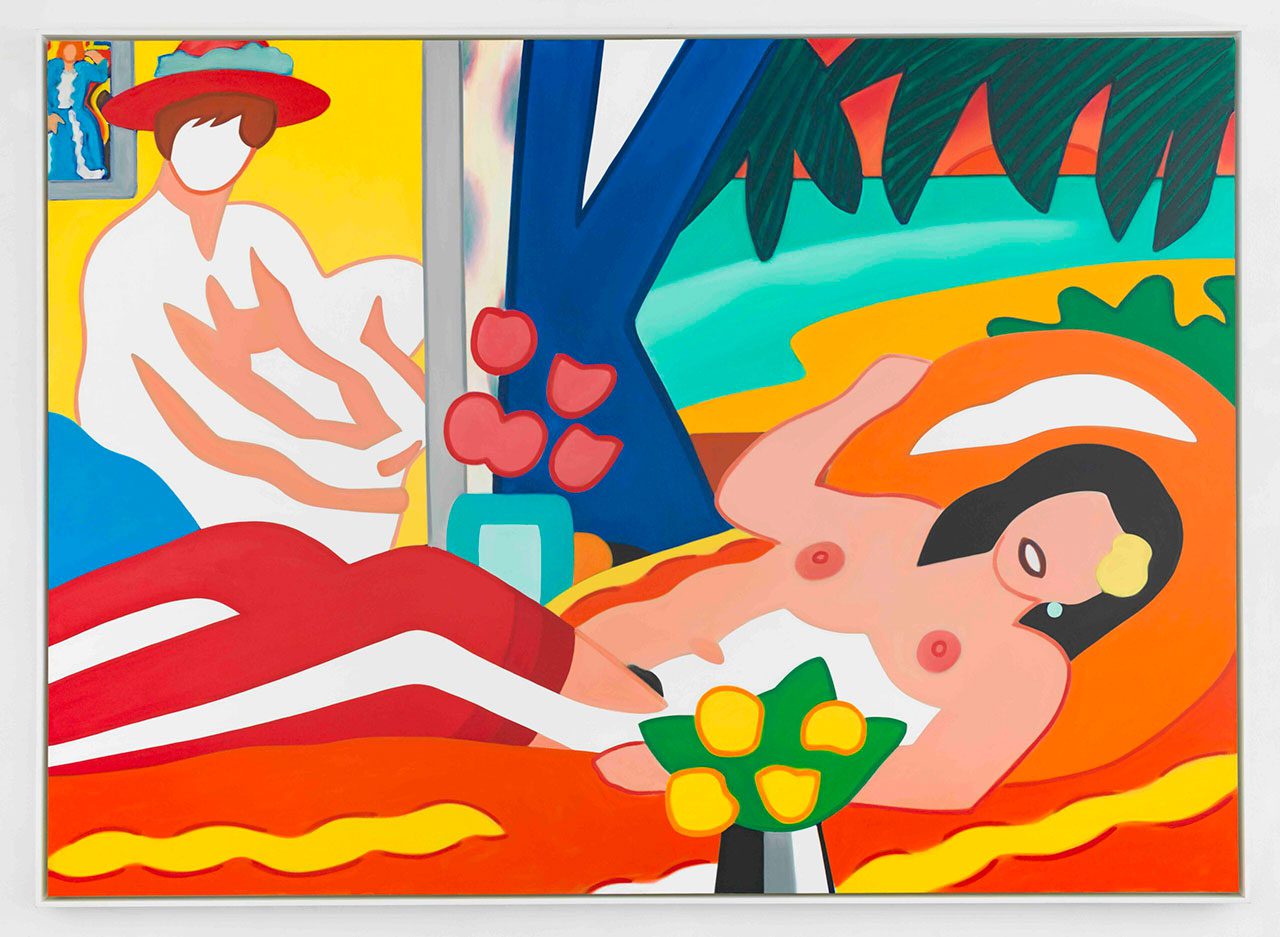

The exhibition “Pop Forever, Tom Wesselmann & …”, is centered around Tom Wesselmann, one of the leading figures of the movement – with a selection of 150 paintings and works in various materials. The exhibition also features 70 works by 35 artists of different generations and nationalities who share a common sensibility for “Pop” – from its Dadaist roots to its contemporary manifestations, and from the 1920s to the present day. In the late 1950s, Pop Art surged on both sides of the Atlantic, in North America and Europe. Comic strips, advertising, cinema, celebrities, food processors and tabloids all became painting subjects. When they were not paintings in themselves, they were photographic images glued or mechanically reproduced onto the canvas. Pop Art celebrates, with a degree of ambiguity, the marriage of art and popular culture, of museums and galleries and the cultural industry. With no manifesto and no boundaries, Pop Art denominates an aesthetic that extends far beyond the artistic realm and prevails to this day. It is difficult to say when Pop Art begins, and certainly impossible to close the chapter on it. In response to the domination of Abstract Expressionism after the Second World War, artists identified with “Pop Art,” which celebrated consumerism and its products as postwar icons. Comic strips , advertising, movies, celebrities, and newspaper headlines all became subjects for painting. This exhibition showcases Wesselmann’s works alongside emblematic pieces from the 1950s and 1960s by his contemporaries Evelyne Axell, Barkley L. Hendricks, Jasper Johns, Yayoi Kusama, Roy Lichtenstein, Marjorie Strider, and Andy Warhol. While Wesselmann incorporated real objects into his works, Johns focused on representing the real, painting a flag and displaying it as an object. “Untitled”( 1967–1968) by Hendricks and later David Hammons’s “African American Flag” (1990), countered with statements about racism. Lichtenstein painted comic-book images as if mechanically printed. Warhol used silkscreen to transform a photo of Marilyn Monroe into an icon. As for Strider and Axell, they subtly challenge male views of consumerism and the female form. In 1959, Robert Rauschenberg wrote: “Painting relates to both art and life. Neither can be made. (I try to act in that gap between the two).” His words express the shared desire of the artists brought together under the term “Pop”: creation between art and life. The sources of their art are found in their daily lives, their identities, the pages of magazines, filmed images, everyday consumer goods, the lighting on signs. Like public and private life, the archetypes and products of 1960s capitalist society are central to their work. Wesselmann and Pop artists explore clichés, promises, and the imagery of 1960s America. This includes the fetishization of the road and the automobile. Wesselmann sought to capture what he called “official reality.” To achieve this, he salvaged posters from New York subway trash cans in order to reproduce scraps of life, and his own long journeys searching for the perfect images. Incorporating everyday objects as fragments of reality, he developed a “concept of a variety of realities,” using flags or presidential portraits to symbolize American culture. Like Jasper Johns’s “Flag”, or the monumental depiction of a smiling John F. Kennedy juxtaposed with a car in James Rosenquist’s “President Elect”, these works evoke the “American Dream.” Beginning in 1962, Wesselmann intensified his collage practice, directly approaching advertising companies to retrieve posters. He started his “Still Lifes” series, incorporating everyday objects, advertising material, and electrical devices. Traditionally, still lifes took on more intimate dimensions, but by combining very different elements, Wesselmann created monumental, aggressive versions. The big red apple in “Still Life #29” comes from one of the very first billboards provided by a manufacturer. It is a significant example of how the poster, its size and impact, add a visual audacity to the work, a crucial element in attracting the consumer’s eye. The works of Marcel Duchamp and his Dadaist contemporaries laid the foundations for Pop Art. Emerging as an “anti-art” movement in Zurich at the very end of the First World War, Dada quickly spread to Berlin, Hanover, Cologne, Paris, and New York. The artists associated with the movement often used collage. Their influence was first directly felt on Surrealism, and after the war was revitalized with Pop Art. Duchamp’s introduction of the readymade—with his “Fountain” (1917) the best-known example—reshaped art history, challenging conventions: anonymous, manufactured objects transformed into artworks. Wesselmann’s early collages, made from materials found in the street, with everyday objects and billboards, are testament to the endurance of the Dadaist legacy. In the 1960s and 1970s, Wesselmann made several “Interiors” and “Shelf Still Lifes”. These fragments of interiors (shelves or entire walls) incorporate television sets and radios. Within a single work, various “realities” — the sound of a radio, an image from a movie, or an item from the news — collide. This period is also marked by explorations in extending the painting’s space. It is characterized by vivid colors and the dynamic effect of the elements that come to meet the viewer, blurring the boundaries of the work even more. In 1961, Wesselmann gained recognition with his Great American Nudes series. Influenced by cultural motifs of the American Dream and the Great American Novel, he incorporated patriotic symbols into his paintings. Additionally, he used pages from magazines, posters, and billboards. Fusing collage, painting, and drawing, he explored a variety of realistic and stylized anatomic representations in this series, bordering on abstraction. Wesselmann’s simplification of form echoes that of the previous work of Henri Matisse. The anonymity of the models, their facelessness, has often raised questions. Wesselmann, though, was not seeking to objectify but to amplify his subjects. He simultaneously conforms to and challenges the artistic canon.

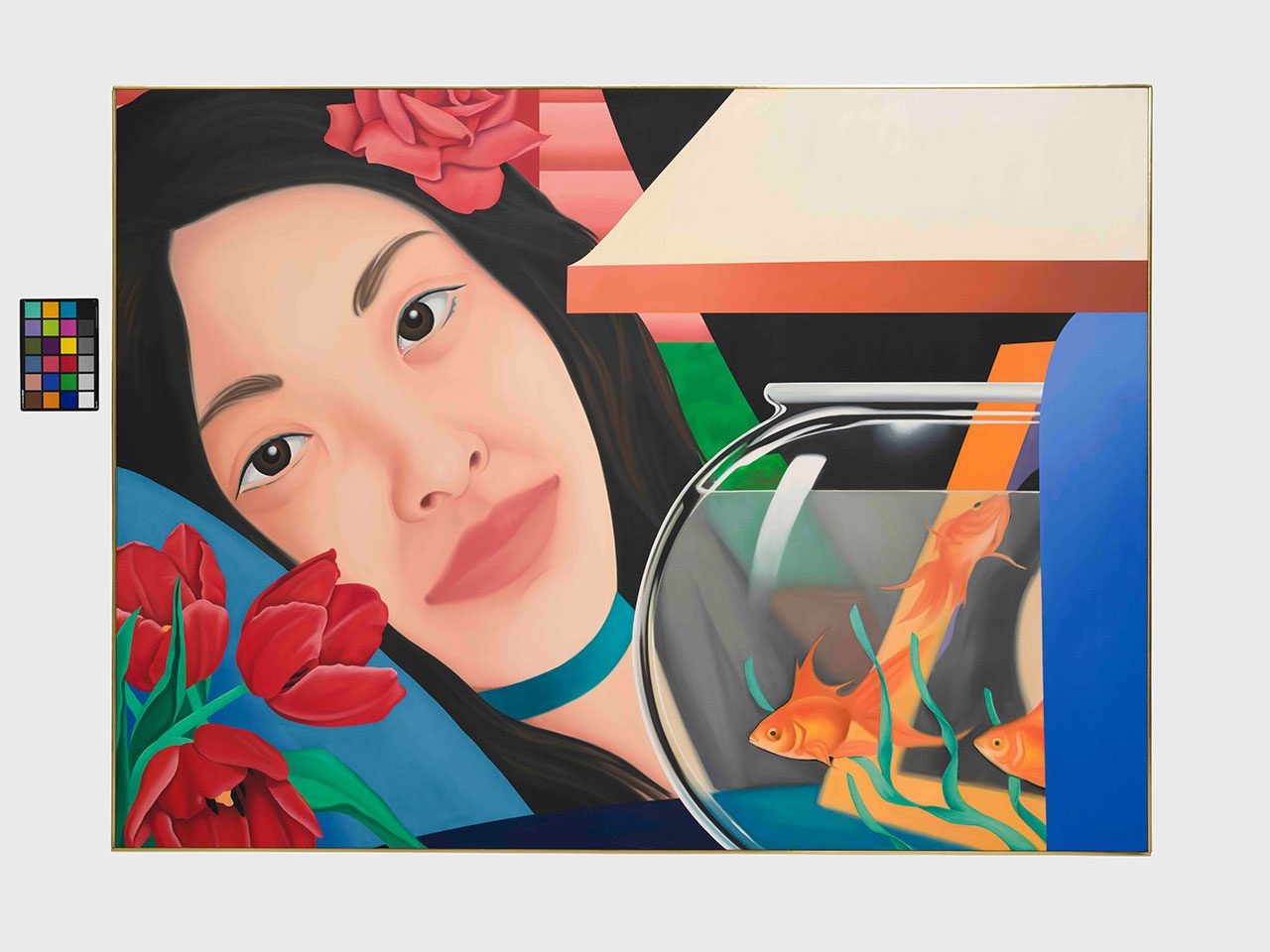

Placed in the context of the sexual revolution of the 1960s, his depiction of female pleasure breaks with the passivity generally associated with the “nude”. Wesselmann’s interest in classical painting genres and the expansion of their traditional boundaries, continues to influence artists across continents and generations. This exhibition juxtaposes his work with that of contemporary artists that resonates with the Pop spirit he helped define. Njideka Akunyili Crosby paints from personal archives, Nigerian magazines, and other mass media to explore African diasporic identities. Do Ho Suh’s fabric sculptures reconstruct previously inhabited interiors and homes, questioning the physical, metaphorical, and psychological dimensions of such spaces. Derrick Adams’s “Super Nudes”, created for this exhibition, can be seen as a counterimage to Wesselmann’s “Great American Nudes”. Also, in the late 1960s, Wesselmann’s compositions became more daring, focusing on isolated details, fragments of bodies imbued with sensuality. For many of his “Bedroom Paintings”, he used shaped canvases, the edges of which follow those of the subjects and objects. He would later use an image of a woman’s body, left in the negative, to define the outline of his canvas, a process he called “drop outs”. These works are complex, combining details from his “Great American Nudes” and “Still Lifes” series. In “Bedroom Painting #43”, the model, Paula Lee, is staring directly at the viewer. The painting’s scale and its realism, which removes the subject’s anonymity, inverts the gaze, redefining roles and narratives in the intimate context of the bedroom. This exhibition celebrates Pop’s persistence. Jeff Koons has continued the spirit of 1960s Pop Art through trivial objects elevated as icons such as “Balloon Dog (Yellow)”. Ai Weiwei’s Pop is critical and globalized. He transformed Han Dynasty urns into symbols of consumer culture with Coca-Cola logos. In similar forms as the paintings of Wesselmann, Tomokazu Matsuyama uses digital tools to produce paintings that reveal, through their eclectic sources, the myriad facets of today’s identities. Meanwhile, KAWS virally multiplies his characters across media, even appearing in spaces via augmented reality, extending the notion of a “variety of realities” that Wesselmann introduced. Nudity had been a part of Wesselmann’s work since his earliest creations. A work such as “Great American Nude #47” reveals his exploration of bold, sexually charged themes that reflect the sexual freedom of the 1960s. His nudes are imbued with joy. The poses taken by his wife Claire convey pleasure. Wesselmann’s representation of sexuality is one of reciprocal desire and shared feelings. In 1965, Wesselmann began his “foot paintings” with elements realized for his “Great American Nudes” series. Replacing an entire figure, the foot as a central subject captivated him with its beauty and considerable potential. The first series to focus on this subject was the Seascapes, set outdoors and coinciding with his first vacations. Following the “Still Lifes”, the “Seascapes” were treated with a similar clear approach. Wesselmann’s meticulous, methodical approach can be compared to scientific experimentation. Each painting or assemblage began with a number of sketches and/or photographs. These initial renderings guided him toward large-scale compositions. His studio practice was systematic and precise, evident in the color and technical details written on the backs of his works, as well as the many notes, sketches, and photographs gathered here. Wesselmann began composing his “Mouth” paintings in 1965. From that time on, the artist worked in oils to capture the most complex, immensely enlarged details. He further perfected the shaped canvas process. In 1967, a glimpse of his friend and model Peggy Sarno lighting a cigarette during a break triggered the Smokers series, with often imposing billows of smoke. Standing in front of Smoker #8, based on a photograph of Danièle Thompson smoking, challenges the viewer. Wesselmann created small oil paintings that he later enlarged using an overhead projector. In the 1970s, he followed these with his “Standing Still Lifes”, enormous works composed of several canvases reproducing small, familiar items on a large scale. The resulting monumentality creates a sense of disjunction with reality: the familiar suddenly acquires a strange dimension, like Alice in Wonderland. In front of these works, visitors seem to shrink. The perceptual distortion is accentuated because these objects retain their pictorial essence, confined to a two-dimensional treatment rather than transitioning into full sculpture. Wesselmann moved away from the “Standing Still Lifes” in the 1980s, when he began drawing with metal. He used different techniques: the aluminum pieces were cut by hand, those in steel were shaped with a laser. A pioneer in the use of new technologies, he forced manufacturers to adapt. Over time, his work in metal, initially figurative, evolved toward an abstraction that could be called expressionist. The assembled cut-outs, painted on the surface, are like rapid brushstrokes. In the last years of his career, these compositions blur the line between abstraction and figuration, and approach sculpture. They were realized in parallel to large, nostalgic canvases. “Sunset Nude with Wesselmann”, for example, includes a detail from one of his early collages. His nudes also attest to a return to a classicism influenced by Henri Matisse.

Works by: Tom Wesselmann, Derrick Adams, Ai Weiwei, Njideka Akunyili Crosby, Evelyne Axell, Thomas Bayrle, Frank Bowling, Rosalyn Drexler, Marcel Duchamp, Sylvie Fleury, Lauren Halsey, Richard Hamilton, David Hammons, Jann Haworth, Barkley L. Hendricks, Hannah Höch, Jasper Johns, KAWS, Kiki Kogelnik, Jeff Koons, Yayoi Kusama, Roy Lichtenstein, Marisol, Tomokazu Matsuyama, Claes Oldenburg, Meret Oppenheim, Eduardo Paolozzi, Robert Rauschenberg, Martial Raysse, James Rosenquist, Kurt Schwitters, Marjorie Strider, Do Ho Suh, Mickalene Thomas, Andy Warhol and Tadanori Yokoo

Photo: Tom Wesselmann

Info: Head curator: Suzanne Pagé, Curators: Dieter Buchhart, Anna Karina Hofbauer assisted by Tatjana Andrea Borodin, Associated curator: Olivier Michelon, assisted by Clotilde Monroe, Fondation Louis Vuitton, 8 avenue du Mahatma Gandhi, Bois de Boulogne, Paris, France, Duration: 17/10/2024-24/2/2025, Days & Hours: Mon & Wed-Thu 11:00-20:00, Fri 11:00-21:00, Sat-Sun 10:00-20:00, www.fondationlouisvuitton.fr/