ART CITIES:Seoul-James Rosenquist

James Albert Rosenquist was one of the proponents of the pop art movement. Drawing from his background working in sign painting, Rosenquist’s works often explored the role of advertising and consumer culture in art and society, utilizing techniques he learned making commercial art to depict popular cultural icons and mundane everyday objects. His works were unique in the way that they often employed elements of surrealism using fragments of advertisements and cultural imagery to emphasize the overwhelming nature of ads.

James Albert Rosenquist was one of the proponents of the pop art movement. Drawing from his background working in sign painting, Rosenquist’s works often explored the role of advertising and consumer culture in art and society, utilizing techniques he learned making commercial art to depict popular cultural icons and mundane everyday objects. His works were unique in the way that they often employed elements of surrealism using fragments of advertisements and cultural imagery to emphasize the overwhelming nature of ads.

By Dimitris Lempesis

Photo: Thaddaeus Ropac Gallery Archive

The exhibition “Dream World: Paintings, drawings and collages, 1961–1968” presents works from a defining decade for James Rosenquist. In these significant early years of his career, Rosenquist extensively investigated the nature of the picture plane. Drawing on his background as a commercial billboard painter, he employed radical disjuncts of scale and enigmatic compositions, using collage techniques and popular imagery from magazines to create his own idiosyncratic visual vocabulary. It was during this decade that he completed what many consider a magnum opus: the room-installation “F-111” (1964–65), now on permanent display at MoMA. His work radically tested the possibilities of perception, of the image and of the painted medium itself, propelling him to the centre of art world attention and establishing his place at the forefront of his time and the nascent Pop art movement. exhibition brings together important works, including monumental painting, shaped canvas and a number of rarely shown studies, preparatory sketches and collages – foundational works for some of his most celebrated paintings now housed in major international museums. Born in 1933 in Grand Forks, North Dakota, James Rosenquist spent his childhood pursuing three main interests: airplanes, cars, and drawing. He liked to draw on rolls of cheap wallpaper, producing long, continuous illustrated stories. He also built model airplanes, inventing his own designs. Rosenquist’s family eventually settled in Minneapolis. As a teenager he took art classes at the Minneapolis Institute of Art and later studied painting at the University of Minnesota. During the summers, he worked as a billboard painter, learning a good deal about figurative and commercial painting techniques from fellow workers. His early training as a billboard painter has continued to influence the scale, content, and style of his works. Many are monumental in scale, contain elements of imagery derived from advertising, and employ commercial painting techniques. In 1955 Rosenquist moved to New York, having received a one-year scholarship to study at the Art Students League. To support himself, he returned to life as a commercial artist, painting billboards in Times Square and across the city. By 1960, Rosenquist had stopped painting commercial advertisements and rented a small studio space in lower Manhattan. Working against the prevailing tide of Abstract Expressionism, Rosenquist soon developed his own brand of “new realism”—a style that would come to be known as Pop Art. Along with contemporaries Jim Dine, Roy Lichtenstein, Claes Oldenburg, and Andy Warhol, Rosenquist drew on the iconography of advertising and mass media to conjure a sense of contemporary life. In 1962, he had his first solo exhibition at Green Gallery in New York and afterward was included in virtually all the groundbreaking group exhibitions that established Pop Art as a movement. In the late 1950s and early 1960s, the focus on collage was not limited to the visual arts, but rather linked to many areas of contemporary city life. In urban planning, Jane Jacobs’s “The Death and Life of Great American Cities” (1961) advocated “urban montage,” an inclusive approach that focused on street life. The essence of collage, in the form of found sounds and the splicing together of otherwise independent theatrical elements, was evident in the music of John Cage and the choreography of Merce Cunningham. In literature, discontinuous narrative and collage were characteristic of the writing of the Beats including writers Allen Ginsberg, Jack Kerouac, and William Burroughs. Burroughs experimented with montage, including cut film and photographs, magazine illustrations, and newspaper clippings. Burroughs’s cut-ups involved cutting up his own writing as well as the work of other authors and randomly splicing them together to create a new text. This approach recalls Surrealist philosophy, which sought unexpected poetic combinations of objects and to infuse an element of chance into the art making process. Rosenquist’s work demonstrates an enduring interest in and mastery of texture, color, line, and shape that continues to dazzle audiences and influence new generations of artists. His paintings allude to the cultural and political tenor of the times in which they were created. They convey impressions and opinions about advertising, politics, beauty, space, and time. Fraught with feeling, they have been called “visual poems” that resolutely resist words.

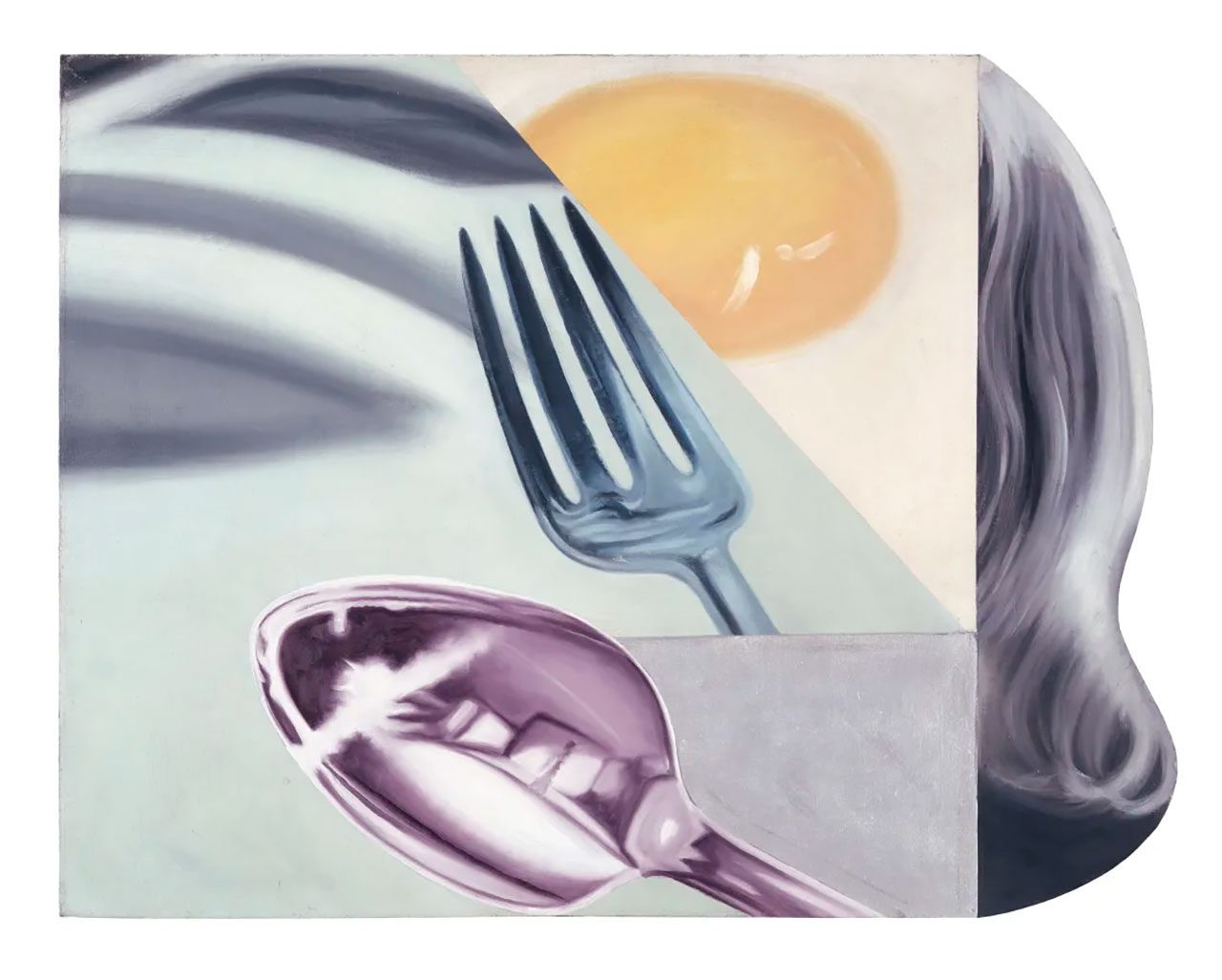

Photo: James Rosenquist, Coenties Slip Studio, 1961, Oil on canvas and shaped hardboard, 86.4 x 109.2 cm, Courtesy James Rosenquist Estate and Thaddaeus Ropac Gallery

Info: Thaddaeus Ropac Gallery, 1-2F, 122-1 Dokseodang-ro, Yongsan-gu, Seoul, Korea, Duration: 21/11/2024-25/1/2025, Days & Hours: Tue-Sat 10:00-18:00, https://ropac.net/

Right: James Rosenquist, Morning Sun, 1963, Oil on canvas and plastic, with twine, bamboo, and metal fishhook, 198.1 x 167.6 cm, Courtesy James Rosenquist Estate and Thaddaeus Ropac Gallery