TRIBUTE: Hans Haacke

Hans Haacke has shaped “political art” to a greater extent than any other artist of his generation. Keen criticism of institutions, political awareness, and an uncompromising defense of democratic principles to the point of activism all characterize his approach. His work is marked by directness and theoretical clarity, and yet it is poetic, metaphorical, ecological, and in many respects highly topical at the same time.

Hans Haacke has shaped “political art” to a greater extent than any other artist of his generation. Keen criticism of institutions, political awareness, and an uncompromising defense of democratic principles to the point of activism all characterize his approach. His work is marked by directness and theoretical clarity, and yet it is poetic, metaphorical, ecological, and in many respects highly topical at the same time.

By Dimitris Lempesis

Photo: Schirn Kunsthalle Frankfurt Archive

Throughout, Hans Haacke’s work is politically rigorous. He was repeatedly excluded from exhibitions due to his directness. He consistently defends his beliefs, particularly the defense of democratic principles. The exhibition at the Hans Haacke’s Retrospective at the SCHIRN, presents around 70 paintings, photographs, objects, installations, actions, posters, and a film from the period of 1959 to the present. Hans Christoph Carl Haacke was born in Cologne in 1936, during the period of extreme social change that saw the rise of the Nazi Government in Germany. By the time he was three years old WWII had begun, and by the age of six bombs regularly fell on the street he lived on. In his own words, “I remember walking by a still smoking ruin on my way to school.” His father was affiliated with the Social Democratic party and refused to join the Nazis, costing him his job with the city of Cologne. Such traumatic episodes led the Haacke family to move from Cologne to a small rural town in the southern district of Bad Godesberg. Haacke’s interest in art was already evident at a young age. His first exposure to art history in high school was a pivotal moment in his life. As he recalls in that class he “learned that art was not just a skill to render something” but that it “had deeper meanings”. In 1956 Haacke enrolled at the State Art Academy in Kassel, where many of the professors taught at the Bauhaus prior to the war. He was also taught during his time in Kassel by the English painter Stanley William Hayter. Through its faculty and location, the school was very much connected with Documenta, the large contemporary art exhibition which still occurs every five years in Kassel, and was first planned as a way to bring Germany up to speed with art and culture after the cultural censorship of the Nazis. Haacke fulfilled several minor functions at ‘documenta 2’ while a student. Around the same time, Haacke hitchhiked to Paris, where he became familiar with Art Informel and Tachisme. It was his encounter with the ZERO group, during one of their shows in the city of Bonn, that most influenced his early works however. The group was devoted to the metaphysical aspect of artistic production and were particularly interested in the relationship between humans and nature, using elemental and industrial materials in their artworks. Haacke soon became friends with Otto Piene, one of the founding members of ZERO, and began to exhibit alongside them. During this time Haacke also produced work that echoed elements of minimalism and land art. Another important influence in his work was the writings of playwright and poet Bertolt Brecht, who he came across during his student years. Like Brecht, Haacke became committed to using art to reveal overlooked truths. After graduating with a degree in art education in 1960, he worked at Hayter’s print studio for a year, becoming acquainted with Yves Klein and other avant-garde artists. Soon after, he received a Fulbright grant which allowed him to study at the Tyler School of Art in Philadelphia. While studying at Tyler School he often took the bus to New York to see exhibitions and make connections with other artists. After briefly returning to Germany at the end of his scholarship, in 1965 he moved permanently to New York City. The American artist George Rickey helped Haacke get his feet on the ground when he first arrived. Rickey got Haacke into shows and introduced him to major figures in the art industry, earning his gratitude, but despite some initial success Haacke was required to teach German in order to support himself. Building on his early work with ZERO, Haacke’s practice continued to develop strategies for revealing the economic interactions of art markets and corporations. He was never a fan of the greediness he identified within it, for example, arguing that “the works in the [art] fair had been reduced to their monetary value.” His dissatisfaction with the art industry (he underscores the use of the word industry instead of field), together with the student revolts around the world, the civil rights movement, and the Vietnam War, affected the new direction his work would take in the 1970s, when his art became increasingly political and critical of art institutions and bureaucratic systems.

In the mid 1960s Haacke married Linda, his life-long partner and had two sons. The birth certificate of one of them, Carl Samuel Selavy, became in 1969 an art work titled “Birth Certificate of My Son (collaboration Linda & Hans Haacke)”. Carl’s last name, Selavy, is an homage to Marcel Duchamp’s alter ego Rrose Selavy, one of his primary artistic influences (alongside Marcel Broodthaers) in his use of the ‘ready-made’ sculpture. In naming his son after Duchamp, albeit through a subtle allusion, Haacke pays tribute and might also subtly be suggesting a baby as the ultimate ‘ready-made’ sculpture. Throughout his career Haacke has never relied on sales to support his family. The teaching position that he held from 1967 until 2002 at Cooper Union, contributing to the foundation program on 3D design and the undergraduate sculpture program, was his main source of income for most of his career. Since the early 1970s he has been using a contract that gives him a percentage of any resale profit and power to determine where his work will be exhibited, regardless of the collector’s wish. Regarding the contract, he says, “it occasionally kills the deal. But I’m coming round to believe that the contract I insist on is a very useful litmus test as to who should, and who definitely should not, own my work.” In 1971, Haacke was offered a retrospective at the Solomon Guggenheim museum in New York, something quite rare for an artist so young. But because of a work in which he exposed landowner Harry Shapolsky’s suspicious business activities, the exhibition was shelved. Guggenheim curator Edward Fry was later fired due to the episode. At the time, Haacke stated that it was a clear case of censorship. The incident shows that censorship as a means of diverting attention from an artwork is rarely successful, as it instead publicized an exhibition that could have easily been forgotten. The show’s cancellation promoted Haacke, who became known to a far wider audience than he had previously. Artists includig Carl Andre boycotted the museum in solidarity. Marcel Broodthaers, one of Haacke’s influences, also publicly criticized Joseph Beuys for exhibiting at the museum in the following year.

Haacke maintained his rigid personal code throughout his career, refusing to participate in the 1969 São Paulo Biennial due to rise of a military dictatorship in Brazil. The Guggenheim controversy was not the only case of censorship throughout Haacke’s career. A few years later, his work “Manet-PROJEKT ’74” (1974) was censored from a German museum for connecting Édouard Manet’s “Bunch of Asparagus” (1880) to the Nazi Party through the former advisor to Hitler Hermann Josef Abs (chairman of the museum that donated it to the exhibition). Proposing a series of 10 information panels tracing the painting’s provenance, Haacke was disinvited from the exhibition. Haacke’s combative political stance became more pronounced with age. In 1985 he created “MetroMobiltan,” now considered the centerpiece of his focus on institutional critique. The work reveals the connections between The Metropolitan Museum of Art, the oil company Mobil, and the apartheid system in South Africa. After “MetroMobiltan”, he developed works that attacked English prime minister Margaret Thatcher, US president Ronald Reagan, and the Saatchi family – some of the most powerful collectors in the art world at the time. Throughout his career Haacke has been simultaneously glorified and vilified for his criticism. In “Sanitation” (2000), presented at the Whitney Biennial, he printed quotes from New York’s former major Rudolph Guiliani assailing artist Chris Ofili’s painting “The Holy Mary Virgin” (1996). Haacke’s use of Hitler’s official typeface fraktur, associating Guiliani and his Ofili criticism was seen by some as associating the episode with the holocaust. Many considered that this connection belittled the horrors of the genocide. Haacke even received threats via telephone and email, some accusing him of anti-Semitism. This charge is complicated by the fact that his wife and children are Jewish, and that he had previously exhibited at the Jewish Museum in New York. Despite his political convictions, Haacke does not vote in the country he has chosen to live in. Even though he has now lived most of his life in America and has the right to become a citizen, he has preferred not to do so. He justifies his choice by saying, “a great number of terrible things have happened in Germany, but that doesn’t mean I can say, ‘Go to hell, Germany.’ Maybe it’s just a sentimental connection to the place of my birth.” In the past years, his works have been voraciously collected by museums. He was also awarded the prestigious honor of having his “Gift Hors0”e (2015) displayed on the fourth plinth in London’s Traflagar Square, bringing his work further into the mainstream.

Photo: Hans Haacke, Grass Grows, 1969, earth, grass seeds, 150 × 300 cm (diameter), exhibition view: Hans Haacke: All Connected, 2019, New Museum © Hans Haacke / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2024, Photo: Dario Lasagni

Info: Shirn Kunsthalle Frankfurt, Römerberg, Frankfurt, Germany, Duration: 8/11/2024-9/2/2025, Days & Hours: Tue & Fri-sun 10:00-19:00, Wed-Thu 10:00-22:00, www.schirn.de/

Right: Hans Haacke, Large Condensation Cube, 1963–67, Acrylic glass, distilled water, 76.2 x 76.2 x 76.2 cm, MACBA Collection, MACBA Foundation, Gift of National Comitee and Board of Trustees Whitney Museum of American Art, © Hans Haacke / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2024, Photo: Hans Haacke

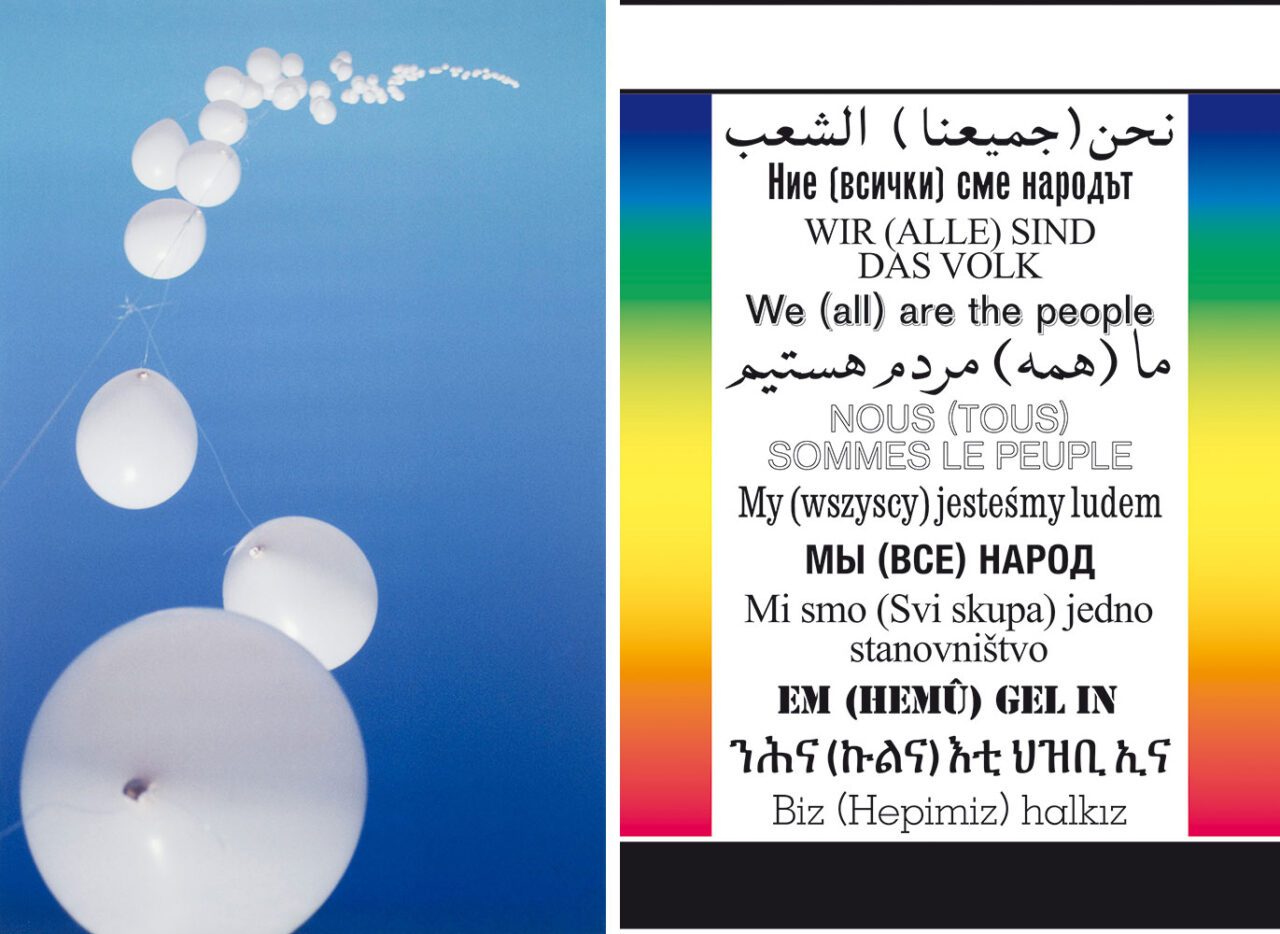

Right: Hans Haacke, We (All) Are the People, 2003/2017, Banners and posters, Variable dimensions, Courtesy the artist and Paula Cooper Gallery, New York, © Hans Haacke / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2024, Photo: Steven Probert

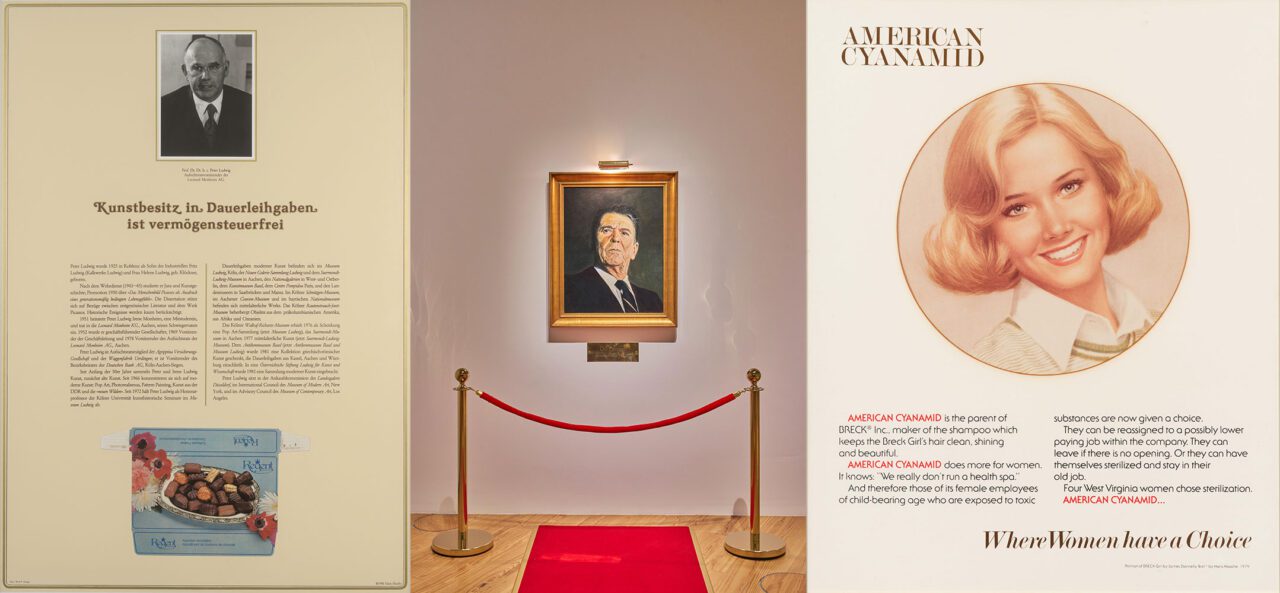

Center: Hans Haacke: Retrospective, installation view: Oil Painting: Homage to Marcel Broodthaers, 1982, © Schirn Kunsthalle Frankfurt 2024, Photo: Norbert Miguletz

Right: Hans Haacke, The Right to Life, 1979, Color photograph on tricolor silkscreen print, 127 x 101 cm, edition 2/2, Courtesy the artist and Collection Lila and Gilbert Silverman, Detroit, © Hans Haacke / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2024, Photo: Steven Probert